Book Review

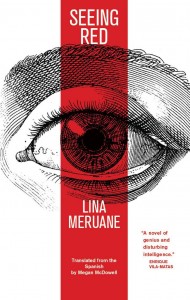

One evening in New York, Lina Meruane’s body “seize[s] up” and leaves her “paralyzed, [her] sweaty hands clutching at the air.” Just as she reaches to her purse to pick up an insulin shot, a “firecracker” goes off in her head: “That was the last thing I would see, that night, through the eye: a deep, black blood.” The stroke leaves her vision damaged, and the rest of Seeing Red, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, concerns how Lina, a writer and doctoral student, copes with losing and trying to reclaim her sight. Every day threads of blood continue to cloud her vision. “Being like this, in a fog,” she says, “is like being asleep and awake at the same time.” In the aftermath, Lina is unable to put pen to paper.

One evening in New York, Lina Meruane’s body “seize[s] up” and leaves her “paralyzed, [her] sweaty hands clutching at the air.” Just as she reaches to her purse to pick up an insulin shot, a “firecracker” goes off in her head: “That was the last thing I would see, that night, through the eye: a deep, black blood.” The stroke leaves her vision damaged, and the rest of Seeing Red, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, concerns how Lina, a writer and doctoral student, copes with losing and trying to reclaim her sight. Every day threads of blood continue to cloud her vision. “Being like this, in a fog,” she says, “is like being asleep and awake at the same time.” In the aftermath, Lina is unable to put pen to paper.

She eventually returns to her native Chile to recuperate with her family, but her siblings and parents are awkward or absent. Her Madridleño boyfriend, Ignacio, joins her, despite her desire to keep him at a distance. Their relationship proves intense but difficult: “It’s a good thing too that you can’t read my mind . . .” she imagines telling him. “I’ll never let you see what’s inside here, things I don’t even tell myself.” Though desperate for some physical contact, Lina is repelled by Ignacio because he cares so much, but also because he—a hypochondriac squeamish at the sight of blood—has no actual idea what she is experiencing.

The author, also named Lina Meruane, and also a Chilean writer and former doctoral student at New York University, suffers from the same affliction as the protagonist. To say Seeing Red is simply autobiographical fiction, though, seems too superficial; as confessional as it is, full of Lina’s troubles and instabilities, it feels more like a tell-all, or more properly like a self-indictment. It plays with the boundary between memoir and fiction by frequently calling attention to the protagonist’s name, such as vacillating between “Lina” and her full name “Lucina.” (“So are you or aren’t you Lina Meruane?” Ignacio asks her the first time they talk. “Sometimes I am,” she replies, “when my eyes let me.”) Lina, the protagonist, terms fiction “one hundred percent pure,” having quit journalism because she falsified information. Some truth can only be conveyed, Meruane seems to be telling us, by drifting away (if only so far) from the facts. Thus it seems intentional that this English translation has no label on it: nothing to indicate fiction or nonfiction, just a blurb from Enrique Vila-Matas calling it “a novel of genius.”

Meruane has won several international prizes for other work, while Seeing Red, originally published in 2012 as Sangre en el Ojo, won the highly regarded Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize. McDowell’s translation, from Deep Vellum Publishing, is the first work of Meruane’s to appear in English. McDowell’s translation impresses with how astutely she renders the author’s fey voice. (A friend tells Lina that one doesn’t “write with just your eyes and hands” and instructs her to “start writing in your head.” This is the book’s voice, a channel into Lina’s psyche, where Ignacio “tripped over a hot water bottle that had fallen to the floor like a dead child.”) The translation also impresses for what is left in Spanish, such as Ignacio’s frequent cursing or his difficulties adapting to the differences between Spain’s Spanish and the Chilean variation. Occasionally Meruane will purposefully leave the ending off a sentence, to startling effect, but McDowell handles those with aplomb, too, rendering the fractured trauma vivid.

“Because as the world went black,” Meruane writes, “everything that belonged to it was also left in the dark.” Returning to New York, she wavers over undergoing a risky corrective surgery. The stroke damages her ability to see that those close to her—such as her mother who, toward the end, makes a desperate offer of her own eyes—are trying to help. She knew for a long time that she was likely to lose her sight, but that knowledge makes the tragedy only sharper. What would it be like to lose one’s sight, especially as a writer, and not be able to see the words on the page? With no other recourse, Lina becomes obsessed with listening to audiobooks, although she would probably prefer to read braille—such, it seems, is the power of writing. This is a diary of struggle; it brings a case that is maybe impossible to imagine into intense focus and, in doing so, is wise enough to draw lightly upon the rich metaphors of sight.

“All that happens to us,” said Borges, whose famous blindness gets a passing nod in these pages, “including humiliations, embarrassments, misfortunes, all is given to us as raw material, as clay, so that we may shape our art.” Few things provide so much of this “raw material” as losing one’s sight suddenly: the immediate dependence on others, the disorientation, the estrangement from the world. In an autobiographical work full of discomfort, Meruane spares nothing negative, and Seeing Red is astounding and essential for it.

About the Reviewer

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Midwestern Gothic, The Millions, Necessary Fiction, Palooka, and Pulp Literature, among other sites and publications. He and his wife, Tiffany, live in Lincoln, Nebraska, with their Yorkshire Terrier, Mocha.