Book Review

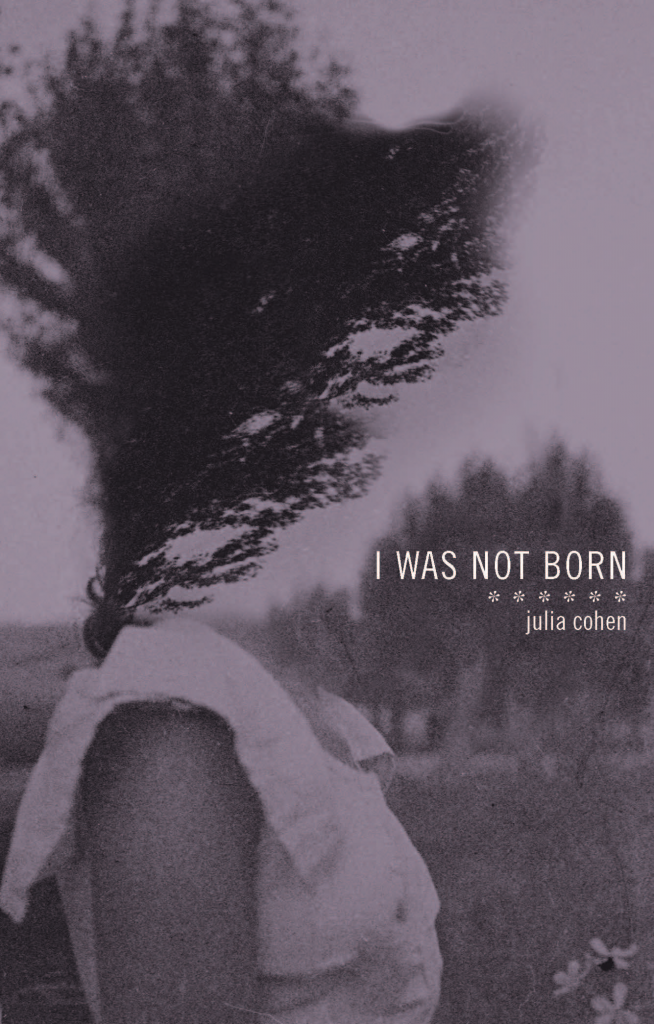

You can read I Was Not Born like a sci-fi novel. Consider Julia Cohen’s hybrid poetry collection centered on a dystopian future in which hope has run out of ideas, the self is nearly dead, and beauty is too undefined to notice. In her stunning first section of the book she writes:

You can read I Was Not Born like a sci-fi novel. Consider Julia Cohen’s hybrid poetry collection centered on a dystopian future in which hope has run out of ideas, the self is nearly dead, and beauty is too undefined to notice. In her stunning first section of the book she writes:

Born in a deadlight. Stop teasing. Furnace full of patient stars. Here because I could not abandon love: coffee grounds, a box of opened cereal, cherry magnets. My bed unburdened by sex? To hold nothing against nothing. To hold nothing against.

From these lines we have no idea what has happened. But the speaker’s worldview has shifted so dramatically that she is focusing on the spectacle of leftover breakfast on the kitchen counter and asking her readers to do the same. We urgently desire to know where we are and what has taken place, what she means by holding “nothing against nothing.” The collection’s title itself has a science fiction mystery to it: if you are not born, what are you?

Alternatively, you can read I Was Not Born like a fantasy novel. Cohen’s writing is freckled with bizarre but finely lit descriptions of a new beginning, a fantastic future in which one is constantly waking up, or reawakening, to a new kind of bliss:

I cannot get warm. I cannot clip the syrup from the homespun tree. Cannot

scrape the banquette into the baby swing. Blue leaves at last. I feel like I can

feel.

Here, Cohen gives us a tactile world alive with all kinds of feelings. “Blue leaves at last” I can’t be sure about, but to me it translates into something strangely comforting and foreboding. This anxious combination comes up often in her work.

Whichever way you read this collection, the true nature of the writing, and the story, is deeply and profoundly imaginative. In the wake of inconceivable confusion and loss, Cohen depicts profound realism. She’s not just going through a tragedy but wearing it, smelling it, feeling it absorb into her skin. Cohen’s speaker is certainly in a strange emotional place—it’s not quite grief she’s enduring, and it’s also not exactly relief; it’s that in-between state she offers us so bravely.

Through sessions with the speaker’s therapist, and bizarrely uncomfortable nights at home with her post-suicidal boyfriend (he didn’t end up going through with it), we enter a place where ideas of salvaging love from tragedy blend with the anxiety of falling out of love. In a smaller, more traditionally lineated poem she writes:

The marvelous independence of

the human gaze.

The moment pursuing,

like a beginning swimmer.

Intelligence objects randomly hurling.

Immediately I loved.

Heavy & vulgarized.

In these lines, Cohen not only catapults us through her emotions of falling in love, she follows through to the end of that experience (or is it the beginning?) when she feels at once heavier and vulgar from that falling.

I Was Not Born presents readers with a story of self against Self and against Other, which is more or less the same struggle. You may think you’ve read a hundred poems like this, but you haven’t. Not like Cohen’s. She covers so much of the human psyche in a relatively short and complete text. And the poems are pleasurable and exciting to read. Her scattered observations mirror her struggle for a solution to heartbreak, and a pining for intimacy:

a bowl of coins lunges for the sun and an unseen squirrel steals tomatoes. Do I live the way I read? The you’s face blurs, a sandcastle blown into the sea by a greedy umbrella. A bellow. Will someone clutch the outside lung? To hum into a bird’s belly.

These are emotions you can taste, see, feel, hear, smell. The experience of pressing your lips against a warm live bird, that closeness and strangeness, is intimate. Also she gives us the presence of “a bellow,” a tool that breathes air into fire.

I realize it doesn’t matter whether Cohen’s boyfriend in the collection really planned a suicide and, luckily, did not follow through with it. It doesn’t matter if Cohen really found that noose in his bag. It doesn’t matter in the same way it doesn’t affect a sci-fi story if a monster about to attack a city is real or imagined, or in a fantasy book if two people from distant planets are searching for the same person to save their dying worlds. What matters is a kind of emotional honesty many writers don’t have. And Cohen has it. I believe her. Her writing is, under a bit of gauze, purely transparent. Cohen helps me feel like I, too, when reading her work am, “Here because I could not abandon love.”

All of this sounds so heavy. And it is. But the way Cohen writes I’m right there with her feeling the oddity of her situation and the authenticity of her emotional responses. For example, as she brilliantly puts it, “It’s tiring keeping someone else alive.” She also eloquently describes the acidity of sharing a home with a person who used to love you. At one point she realizes maybe staying in the relationship is hurting her, that maybe caring about herself is more important right now. She reports: “I buy green sheets. I buy five succulents, place the jade plant in the birdcage. I buy a vacuum cleaner. I buy a coffee table. I buy two shelves. I cry with a sadness that is never about one thing.” Recovery doesn’t usually happen by suffering what you want to suffer—the regeneration of a romance, years of trying to make it “work.” It’s harder than that.

Published 4/21/2015

About the Reviewer

Mollye Miller received an M.F.A. in poetry from The New School, where she received the 2010 Chapbook Award for Shade Particles. In 2012, she won the Maureen Egen Writers Exchange Award for her manuscript What Was Done. Her poems have appeared in Paperbag, elimae and Stop Sharpening Your Knives (SSYK), a UK anthology of poetry and illustration. She lives in Baltimore.