Book Review

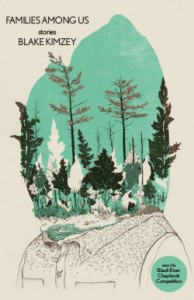

The idea of aliens living among us has excited the imaginations of spiritualists, conspiracy theorists, and street-corner doomsayers even before the Roswell UFO crash of 1947. Such speculation has also, through the years, provided rich fodder for storytellers of all forms. Following the likes of Orson Welles and his radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, Rod Serling and the television series The Twilight Zone, and John Carpenter and his film The Thing, Blake Kimzey and his chapbook collection of short stories Families Among Us delve deep into different, yet equally mysterious phenomena. Winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition, Kimzey introduces a cast of wildly bizarre characters, who, unlike those of his predecessors, pose no real threat as they live among seemingly normal human beings. Nor do they hail from exotic locales, outer space, or the netherworld. Instead, Kimzey’s collection proposes that we need look no further than our own homes and communities for the source of the curious and the bizarre, and it is through these otherworldly, yet earthly, creations that we discover that which binds us all.

The idea of aliens living among us has excited the imaginations of spiritualists, conspiracy theorists, and street-corner doomsayers even before the Roswell UFO crash of 1947. Such speculation has also, through the years, provided rich fodder for storytellers of all forms. Following the likes of Orson Welles and his radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, Rod Serling and the television series The Twilight Zone, and John Carpenter and his film The Thing, Blake Kimzey and his chapbook collection of short stories Families Among Us delve deep into different, yet equally mysterious phenomena. Winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition, Kimzey introduces a cast of wildly bizarre characters, who, unlike those of his predecessors, pose no real threat as they live among seemingly normal human beings. Nor do they hail from exotic locales, outer space, or the netherworld. Instead, Kimzey’s collection proposes that we need look no further than our own homes and communities for the source of the curious and the bizarre, and it is through these otherworldly, yet earthly, creations that we discover that which binds us all.

Kimzey’s characters are from the middle, the oft-overlooked places where we assume nothing extraordinary happens: Michigan, Iowa, Idaho, even a North African neighborhood of Paris that goes unnoticed by tourists. But Kimzey’s characters remind us that within these seemingly quotidian locales live people who are anything but ordinary. For example, a young boy, born with a subtle curve of his spine and a partial exoskeleton, “never [makes] the cover of the black and white tabloids at the supermarket even though he learned to fly before he hit puberty.” Another is a young woman who, hidden beneath her full burqa, sports black talon-toes, a mottled tail, orange eyes within a round plate-like face, and a head that “turned all the way around as if it rested on a ball bearing.” These bizarre characters come alive, not as freak show exhibits, but as oddly ordinary individuals born into otherwise typical human families and living within the complexities of normal family life.

Throughout each story run themes of love, joy, loss, and grief. In the first story of the collection, “A Family Among Us,” a family of four makes a unanimous decision to emerge from the sea, leaving the fuselage of a downed Pan-Am flight that has been their home for years. Their gills soon fade as they grow accustomed to breathing with their lungs, and they eventually learn to once again wear clothing, use their legs, and speak with their voices. Not every member of the family is pleased with the change, however. The young teenage girl, as we might expect, is the first to break rank, choosing to go naked and speak only with her eyes. Her brother soon follows suit. To their parents’ consternation, the two spend increasingly more time in the sea, practicing holding their breath for longer and longer intervals. But their attempt to make a permanent return to the sea—to reject their parents’ efforts to adjust to life on land—results in tragic consequences. Standing on the shore, mourning the loss, the parents also decide to return to the dark of the sea, sinking “deeper and deeper, until everything was dark and their thoughts of land were no more.”

In each story, family members struggle with differences, disappointments, and departures. In some, parental love knows no bounds, as in “Tunneling,” in which a father adores his son in spite of the concentric rings around the child’s abdomen that “produced a steady coat of mucous from his pores,” allowing the boy to tunnel through the ground while eating dirt. The boy is still his father’s greatest joy, and the father recognizes “the family logging genes with pride.” Or in “The Boy and the Bear,” a mother, father, and their son must face the horror and heartbreak of realizing that sometimes families must live apart in order to survive. In still another, a father confesses to the shame of his unwed daughter’s pregnancy, yet plans to care for her as she prepares to lay her eggs in the forest outside Paris.

Kimzey’s narrative voice remains largely distant: The characters are nameless, referred to only as the boy, the girl, mother, father, sister, brother. Initially this voice comes across as impersonal and awkward, and it might have grown tiresome in a longer collection of stories. As a tightly and effectively controlled chapbook, however, Kimzey makes it work to his advantage. He adeptly uses this distant voice as a means of emphasizing the emotional universality in the unreal and unique, as when the mother, facing tragedy in “A Family Among Us,” went to the father and “buried her head in his chest and started to whimper. . . .” The generic labels allow us to see that it is the emotional relationships and experiences that make us, if not necessarily wholly human, at least undeniably connected.

While God and religion come up in several of the stories, “And Finally the Tragedy” seems to elevate the ordinary experiences within the collection, if not to the heavens, to a place simultaneously near and far. The narrator, a preacher in an unnamed village, is in search of a missing boy. He sets out with the boy’s parents and a search party of townsfolk and blood hounds who find the boy lying in a field having “tumbled from the stars . . . swinging satellite to satellite.” The boy, still alive, opens his mouth to reveal a projector spinning film and casting images into the night sky. No one fully comprehends these images, yet, in the end, the preacher says, “one by one our bodies turned to dust, salting the wind, and our soul burned in the boy’s imagination, forever alight.” What the townspeople see and what the reader discovers is that the only reality that can transcend the space between land and sea, human and animal, indeed, heaven and earth, is an interpersonal relationship. The essence of our being is not what bodily form we take, but how we exist to one another, and the acceptance that in places we might never imagine there are indeed families among us.

About the Reviewer

Susan Donnelly Cheever is an English teacher and poet. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts.