Book Review

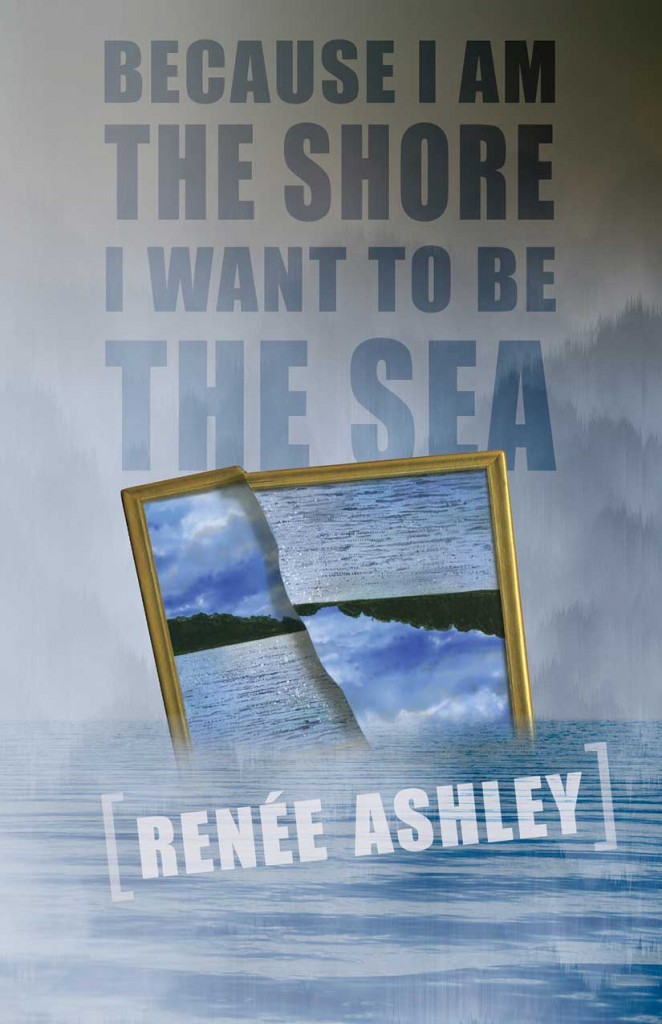

Selected by Ruth Ellen Kocher as the winner of the Subito Book Prize, Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea is Renée Ashley’s fifth full-length collection. Comprised entirely of prose poems, Ashley experiments with metaphor to translate life into image and image into life for an ambiguous but deeply satisfying analysis of what it means to be.

Selected by Ruth Ellen Kocher as the winner of the Subito Book Prize, Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea is Renée Ashley’s fifth full-length collection. Comprised entirely of prose poems, Ashley experiments with metaphor to translate life into image and image into life for an ambiguous but deeply satisfying analysis of what it means to be.

Lyrical in composition, the prose poems are paced through language and rhythm rather than punctuation. The author employs occasional colons and em dashes, but these poems express a continuation in thought that omits periods and commas from use. Like life, the prose goes on without pause, urging diction alone to carry the weight of meaning. The result is a sometimes adrenaline-rushed momentum accompanying scattered thoughts and, at other times, a toned down pace to encourage reflection in lines more lulled.

Early in the collection, Ashley’s speaker addresses an overarching narrative theme that weaves in and out of the forty-eight poems: “We are close to listening and these are stories out of what is.” At its heart, Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea traces life in all its forms, weaknesses, and inconsistencies mirroring both a plain-as-day reality and a pensive surrealism that results from looking closely, microscopically, at everyday actions and objects. The grandiosity of life is at once reveled and mystified in “[essay on observation],” as mid-flight birds and ground-bound animals intermingle during a downpour and signify “A whole world coming down onto the world.” There is too much world to contain, the narrator suggests, and what we see of the world around us is a mere micro-world. For every tangible thing we can know and touch, the poem suggests, there is tenfold that is unknown and untouched.

The collection’s narrator takes turns with micro and macro lenses, examining mass alongside minutiae. This approach is exemplified in “[nothing less than less than nothing]” with its playful but bittersweet look at how one’s “articles” and “things” are found or lost in a heartbeat and how “You have forgotten the words you need to say” or perhaps “the saying of what might really matter of what so surely you will never say at all.” From misplaced keys to breathing in and breathing out, the narrator argues life is simultaneously complex and simple and it is in letting the pieces fall where they may that we have any hope of understanding “A rubric of simplicity.” It is what it is, whatever it may be.

Most poems in this collection are neatly packaged in less than half a page of tight block prose, but the title poem is a five-part series spaced evenly across five pages. The series opens up by focusing on the frustration of “wanting to be what you cannot—except by extension—and the bearing of those secrets so immeasurable not even an ocean can conceal them.” It is the pain of human limitation that this first piece of the series focuses on before transitioning into a dreamlike sequence where the narrator addresses how the “world is encoded indelible with lonely and sorry with no with please with no that never happened.” Here, the perceivable and inconceivable align in an abstract image that is both open to interpretation and precisely expressive at the same time.

Another series poem, “[experience],” presents nine brief pieces within immediate succession of one another and, combined with the staccato rhythm of diction, results in a lively syntax: “You stuff envelopes You sit kids You hate kids Your tongue’s stuck to your lip.” In this poem, the speaker lays out one mundane job after another, from flipping burgers to working retail during the holidays; the content and syntactical droning work together to bring to life the experience of ordinary jobs and their necessity in earning one’s keep.

Whether contemplating the numbing minutiae of how to pay the bills or the grandiosity of the universe and “that stuff about death,” Renée Ashley offers concrete and vivid language to accentuate and contain the abstract. Big images become small and tiny specks enlarge for a sensory interplay that is fresh and surprising. Memory, experience, and perception are all challenged while opening up the purpose of each for further inspection. No thought is secure in this collection. There is no certainty in any single thing. The naming and renaming of life’s familiarity widens the interpretative path: “Let’s call the heart a stone No we’ve used up heart and stone… So vessel it is and it breaks.” In life there is movement and the poet encourages flexible footing on insecure ground through the willingness to adapt and weather storms, as expressed in this memorable and hypnotizing collection.

Published 6/30/2014

About the Reviewer

Lori A. May writes across the genres and drinks copious amounts of coffee. Her writing has appeared in Brevity and The Atlantic, and her sixth book, The Write Crowd: Literary Citizenship & the Writing Life, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in December 2014. She lives online at www.loriamay.com.