Book Review

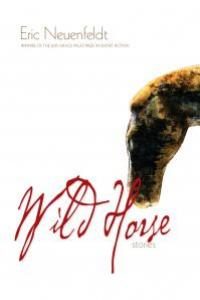

The protagonists in Eric Neuenfeldt’s story collection, Wild Horse, winner of the 2015 Grace Paley Prize, are mostly young and male and disappointed by life. There’s a snowplow driver and a freelance scrap-metal collector. There’s the former athletic director of a junior college who teaches remedial reading at a prison. There are multiple bicycle repairmen and one would-be bicycle repairman who fixes bikes in a sort of yurt behind a rich guy’s house. To varying degrees, these men are tough guy know-it-alls with me-against-the-world mentalities. Men who see themselves as superior to those around them. We, the readers, are bewitched by their inner lives, as well as by Neuenfeldt’s rich descriptive writing, and so we’re tempted to see these stoic loners as they see themselves. But Neuenfeldt gives us clues that the distance between these men and their surroundings may have less to do with their superiority than with their disagreeable and aggressive personalities. We wonder if, despite their intelligence, they’re a little dysfunctional. There’s a whiff of ineptitude about them.

The protagonists in Eric Neuenfeldt’s story collection, Wild Horse, winner of the 2015 Grace Paley Prize, are mostly young and male and disappointed by life. There’s a snowplow driver and a freelance scrap-metal collector. There’s the former athletic director of a junior college who teaches remedial reading at a prison. There are multiple bicycle repairmen and one would-be bicycle repairman who fixes bikes in a sort of yurt behind a rich guy’s house. To varying degrees, these men are tough guy know-it-alls with me-against-the-world mentalities. Men who see themselves as superior to those around them. We, the readers, are bewitched by their inner lives, as well as by Neuenfeldt’s rich descriptive writing, and so we’re tempted to see these stoic loners as they see themselves. But Neuenfeldt gives us clues that the distance between these men and their surroundings may have less to do with their superiority than with their disagreeable and aggressive personalities. We wonder if, despite their intelligence, they’re a little dysfunctional. There’s a whiff of ineptitude about them.

The degree to which the protagonists suffer from this pathology correlates with age. In the opening story, “Gar,” the protagonist is still a teenager. He resents his lawyer cousin and spends the second half of the story needling the older man. But in the climax—an act of physical aggression while fishing—it’s the protagonist, not the cousin, who falls in the water, and we sense that his ambition to hang onto his family home will topple as well. The character is fierce but inept, unfit for the changing world. And his story sets the template for the stories to come, stories whose protagonists may seem more functional.

In “Alley Cat,” we may wonder why Truck, the obnoxious impresario of the cycling community, dislikes the protagonist, Dan, a lowly repairman—until we learn Dan sabotaged Truck’s bike. Though we’re drawn to Dan, the thoughtful outsider, we wonder if Truck really deserved the dangerous prank. Similarly, when Dan relates, with relish, how he conned a “bro” by selling him “a piece a shit mountain bike made to look like it was extreme and expensive when really anyone who knew anything about bikes knew you could never take the thing off road . . . so I’d get him for the cost of the bike and the repairs later,” we aren’t surprised when, later in the story, the same “bro” distracts a policeman while Dan escapes. Put simply, Dan is an unreliable narrator. We can’t trust that the things he dislikes deserve our dislike, and we start to wonder if the world might not be quite as shitty as he makes it out to be.

There’s a similar dynamic in “Gritters.” The story’s protagonist, a snowplow driver, spends a solid paragraph complaining about Donny Beller, the eccentric coworker riding along with him: how Donny wears the same shirt every day, lives with his mother, etc. But, in the end, it’s the protagonist, not Donny, who breaks protocol by parking his snow plow across the street from his own home in order to catch his girlfriend cheating. It’s Donny who says, “I don’t know what’s going on . . . you’re making me real uncomfortable, bud,” and we’re right there with him.

Like their protagonists, the stories in Wild Horse are mostly cut from the same cloth. For some readers, the repetition may be a turnoff, but, for my own part, I appreciated Neuenfeldt’s finely tuned ability to write these characters and to place them in their gritty surroundings (the streets and repair shops of Milwaukee, mostly). That said, the story that most impressed me was an outlier. The protagonist of “Bee Inside a Bullet” is a young man and a cycling enthusiast, yes, but, unlike Neuenfeldt’s other protagonists, this man has moved to the Bay Area to expand his horizons. His girlfriend isn’t an addict but a scientist who studies bees. But what really sets the story apart is that it’s written in second person. Such a potentially contrived choice might seem antithetical to the realism Neuenfeldt employs in the rest of the collection, but it works here, I think, because it allows Neuenfeldt to enter a different register, and, in doing so, to explore unexpected areas of his protagonist’s consciousness. At the end of the story, the protagonist imagines moving again, and his fantasy of life on a Wyoming sheep pasture, living in an A-frame cabin, brings him to life more vividly than the gritty realities of any of Neuenfeldt’s other protagonists.

I recommend Wild Horse to fans of literary fiction and, in particular, to fans of the kind of tightly written stories about working class people that I associate with Raymond Carver. Like Carver’s, Neuenfeldt’s style is noteworthy. His descriptions are crammed full of industry-specific nouns, especially if that industry happens to be bicycle repair. Here’s one from a story called “Temper”:

Grandma Jo was right: Landry kept a filthy shop. There were piles of orphaned parts everywhere—derailleurs he’d poached pulleys from, hub bodies he’d disemboweled. He thought chores like cleaning were a waste of employee time, and he sure as hell wasn’t going to sweep, mop, or dust himself. Most shop owners I’d worked for would hire some kid from one of the shady neighborhoods to scrub the toilet and floors after school—that’s how everyone in the bike biz gets their start—but not Landry. The solution circulator on our parts washer had been busted since spring, and he just told us to deal and clean parts in the murky degreaser.

I recommend this book to cycling enthusiasts as well and to people nostalgic for, or curious about, Milwaukee. Are you a bicycle messenger from Milwaukee who keeps a copy of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love in your back pocket? Maybe Wild Horse will come out in paperback. Fingers crossed.

About the Reviewer

Bradley Bazzle is the author of the novel Trash Mountain, forthcoming from Red Hen Press. His short stories appear in New England Review, New Ohio Review, Epoch, Web Conjunctions, and elsewhere, and have won awards from Third Coast and The Iowa Review. Some of them can be found at bradleybazzle.com. He lives in Athens, Georgia, with his wife and daughter.