Book Review

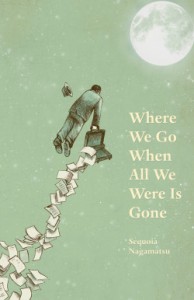

“Do not attempt any of the above outside a magical realm. May cause serious injury or death.” This warning accompanies “Technique for Deep Sea Diving,” one of the short pieces—among them how-to manuals, recipes, and checklists—which counterpoint the longer works in Sequoia Nagamatsu’s remarkable collection, Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone. According to the author, proper diving technique requirements include the following: “With the needle of an urchin, cut five slits into your flesh spaced approximately 1.5 inches apart and measuring the length of your palms. The placement of the slits is up to you (Most choose their neck or lower back).”

“Do not attempt any of the above outside a magical realm. May cause serious injury or death.” This warning accompanies “Technique for Deep Sea Diving,” one of the short pieces—among them how-to manuals, recipes, and checklists—which counterpoint the longer works in Sequoia Nagamatsu’s remarkable collection, Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone. According to the author, proper diving technique requirements include the following: “With the needle of an urchin, cut five slits into your flesh spaced approximately 1.5 inches apart and measuring the length of your palms. The placement of the slits is up to you (Most choose their neck or lower back).”

Do not attempt outside a magical realm, indeed. The magical strongly characterizes Nagamatsu’s fiction, which draws freely on fantasy and the speculative, but to classify his aesthetic according to established genres is to do it an injustice. His narratives and characters float between the enchanted and the real, in a literary space Amber Sparks, writing for the website Electric Literature, called “domestic fabulist.” In Nagamatsu’s fiction, fantasy is not an escape from reality, but a mirror in which we can examine ourselves and cope with the everyday; by making a broader imaginative spectrum available, fantasy has a similar effect on the range of human emotion. Reality demands one set of responses, unreality another, and Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone is characterized by both: here be dragons, but humans as well, and the two are as likely to collaborate as they are to compete.

In an author’s profile from Black Lawrence Press, Nagamatsu says, “as a Japanese American, these stories are my journey in understanding the tensions of where my great-grandparents came from, a way for me to look a bit differently at the pains that many of us experience at some time or another via the magic of a country that I never felt a connection with until recently.”

Written during a stay in Japan, the stories map the Japanese cultural, historical, and political landscape, and by presenting the fictional as real and vice versa, they interrogate that country’s complexities and singularity. In “The Return to Monsterland,” the widower of a biologist who studied kaiju, the generic term for Godzilla and his associated creatures, makes a melancholy visit to a kaiju refuge. “Two weeks living on the island preserve we’ve created for them, and I still can’t wrap my head around the love my wife felt for these creatures.” The circumscribed life of the kaiju in the refuge, and the restrictions memory imposes, point us toward the lessons that strike us only when it is too late. The narrator, through kaiju, reflects back on his love for his wife: “Maybe I thought marrying my best friend and colleague would be enough, and the rest would take care of itself.” One wonders where and what “Monsterland” might be—a theme park, a memory, a marriage, or perhaps all of the above.

The first-person narrator of “Rokurokubi” suspects his wife of an affair, and though this roots the story in domesticity, he is no ordinary husband. He has the ability to stretch his neck across great distances; thus his head can follow his wife to a tryst, visit friends across town, or explore the heavens. Typical of Nagamatsu’s characters, the narrator’s wonder at the world and his place in it is palpable, and grounded in the real even as it intersects the fantastic: “There is something very close to childhood about not having the rest of your body around—the helplessness of not having your arms, the emasculated aspect of your genitals being halfway across the city.” He has not told his wife about his neck-stretching, and the story parses the tension between liberation and limitation. With his head far above the earth, he muses:

After a lifetime of observing people in private moments, I should have learned something. I should know what to do. But maybe that’s my curse, my punishment for whatever I screwed up in my past life. I can see the world but never really be part of it, never live honestly. And what kind of relationship survives on secrets and lies?

Such unusual first-person narrators populate the book, and the inherent intimacy of the perspective is one way Nagamatsu infuses the otherworldly with the relatable. In “The Inn of the Dead’s Orientation for Being a Japanese Ghost,” the innkeeper announces, “Yes, I am Oiwa, the grudge with the never-ending hair, and I am the Keeper of the Inn of the Dead. Welcome!” This remarkable story is a primer on how ghosts come into existence (Nagamatsu’s realistic approach to the paranormal ensures that we don’t question this), an exploration of agendas ghosts might have, an instruction manual for the ghosts themselves, a collection of mini-stories inside a larger one, a treasury of Japanese cultural and social references, and an amusement park ride through ironic distance. It is a ghost story for those who don’t believe in ghosts, and a bridge between the spirt world and the tangible one. One rarely reads a piece so marked by the delight of the author at work, yet so untouched by an author’s agenda or encroachment.

In “The Passage of Time in the Abyss,” Nagamatsu creates what for many readers may be the collection’s signature achievement in bridging the real and unreal, the current and historical. What seems a straightforward narrative of a boat in a storm makes a sudden detour into the legend of Urashima Tarō, a figure in a beloved Japanese fairy tale. (This is not the only such tale referenced in the book, and readers may want to become acquainted with Japanese fairy tales in general for how they inform Nagamatsu’s literature and because they are lovely stories in themselves.) Here Nagamatsu tells parallel tales of the sea: one is his own, another is his rendering of this centuries-old tale. He pans back and forth between them, gradually closing the distance until, like the reality and fantasy from which he makes his stories, the dividing line becomes appropriately blurred. The timeline of the story spans centuries, and its moral and humanistic implications are timeless.

These are high ambitions, and Nagamatsu, in the tradition of Gabriel García Márquez, Haruki Murakami, and others who do not limit their literary phenomenology to the verifiable, writes with a confidence and inclusivity which show he has thoroughly explored the territory beyond realism. Readers may initially find themselves disoriented, but soon understand that this is the first step to discovering more about the world they already know, or thought they did. As Urashima Tarō, the character in a Japanese fairy tale as well as in “The Passage of Time in the Abyss” wonders, “Is he creating the story or is the story creating him?” Readers of Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone may well ask the same question about themselves.

About the Reviewer

Geoff Kronik lives in Brookline, MA and has an MFA from Warren Wilson College. His fiction and essays have appeared in Salamander, The Boston Globe, SmokeLong Quarterly, The Common, and elsewhere.