Book Review

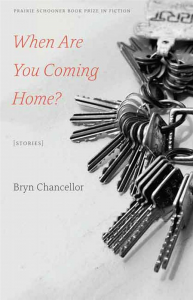

Bryn Chancellor’s When Are You Coming Home?—winner of the 2014 Prairie Schooner Book Prize for Fiction—is a solid, captivating debut short-story collection. Can I be honest here? For several years I’ve submitted my own story collection manuscript to the Prairie Schooner Book Prize and other book contests, and I’m always intrigued to see what the judges ultimately select. It’s not a matter of sour grapes but more the question: what is this collection doing that sets it apart? Or what can we learn from it? Chancellor’s is a collection to aspire to—it feels cohesive and each of the nine stories, set primarily in Arizona, carries its own weight and import. The humor woven throughout is subtle yet effective. We trust the voice and sensibility, and, most importantly, Chancellor elevates her book through her sensitivity and through an abiding awareness that her characters’ lives are meaningful. This may sound like a simple thing to achieve but it isn’t: she convinces us that these people and what they’re going through matter.

Bryn Chancellor’s When Are You Coming Home?—winner of the 2014 Prairie Schooner Book Prize for Fiction—is a solid, captivating debut short-story collection. Can I be honest here? For several years I’ve submitted my own story collection manuscript to the Prairie Schooner Book Prize and other book contests, and I’m always intrigued to see what the judges ultimately select. It’s not a matter of sour grapes but more the question: what is this collection doing that sets it apart? Or what can we learn from it? Chancellor’s is a collection to aspire to—it feels cohesive and each of the nine stories, set primarily in Arizona, carries its own weight and import. The humor woven throughout is subtle yet effective. We trust the voice and sensibility, and, most importantly, Chancellor elevates her book through her sensitivity and through an abiding awareness that her characters’ lives are meaningful. This may sound like a simple thing to achieve but it isn’t: she convinces us that these people and what they’re going through matter.

Some of the characters in When Are You Coming Home? might be described as poor or humble or everyday—the nighttime irrigation guy, the schoolteacher, the restaurant workers, the retired handyman, the woman who sells crafts at the arts festival. Many consciously have given up their hopes, maybe never believed they could realize them, and accepted that a so-so life may be all they’re allotted. Despite navigating this murky disappointment, these characters still reach moments of lightness. Even those stories of disconnections—whether husbands from wives, or younger restaurant coworkers from older love interests, or distraught dumped women from strangers in airports—allow for a small bit of kindness. Perhaps you could say the collection itself is a testament to these ordinary people, is recognition of their importance.

The book opens with the title story of an older father coping with the after-effects of violence committed by his now-deceased son. In many ways he seems estranged from his life, and his attempts at reconnecting with his wife and any semblance of his past seem impossible. This fairly straightforward narrative ends with dynamic imagery and has a lovely missed connection, or an almost made connection, that thwarts reader expectations in a way that feels true to the character’s sensibility.

Chancellor’s characters often struggle to see beyond their present existence, with each story often leading to a moment when they finally can look up. “Wrestling Night,” for example, ties together two forlorn characters—a divorcing high school teacher and one of her bullied teenage students—in the unlikely arena of a neighborhood wrestling ring. Each is described separately as having the inability to see beyond his/her current heartbreak (the divorce/betrayal and the bullying), yet both are ultimately led to a shared point of awareness and light. Maybe it’s inappropriate to say that this story made me cry, but it did. Several in the collection did, actually. Chancellor deftly makes readers care about these people, shows characters at their most vulnerable, and though she doesn’t always spare them terrible ends, she still manages to give them respect and dignity. That she doesn’t judge them seems to be the key here.

From a craft perspective she also uses time in interesting ways to excavate these heartbreaks. “Wrestling Night” achieves its climax by suspending its final moment through a series of flash-forwards that go as far as revealing a character’s eventual death. This time leap gives the story’s last gesture, grounded in the present moment in the ring, both the weight of importance and a weightlessness when held up against the trajectory of an entire life.

Also navigating a wide expanse of time, the stories “Meet Me Here” and “This Is Not an Exit” explore mother–daughter relationships in which the daughters, now adults, must negotiate their mothers’ new identities. One widowed mother expresses her grief through plastic surgery and travel, and the other suffers from Alzheimer’s; the daughter in each seems to live in the shadow of parental disappointment. Both stories allow for sharp, confrontational dialogue (“I’m not getting any younger,” the plastic-surgery mother in “Meet Me Here” says. “I wouldn’t say that,” the daughter replies). Both of these stories also play with different time devices. “Meet Me Here” uses a photograph as a portal: the widow recreates a photo she and her husband had taken decades before, leading her daughter to imagine a photo of her future self standing with a future daughter she didn’t know she wanted. “This Is Not an Exit” uses a retrospective narrator poised on the edge of her mother’s death, remembering when her mother was still well enough to annoy and fight. This structure allows the narrator to circle back to a fixed point for the story’s end, returning to a memory she still attempts to comprehend. These almost parallel mother–daughter stories anchor the collection, depicting people whose shared histories are long, intense, and often fraught. Their connections have had years to develop, a sharp contrast to the stories in which the connections are new, faint, and untested.

In the middle of the book are several missed-connection stories—“Water at Midnight,” “Any Sign of Light,” and “At the Terminal”—fairly simple narratives hinging on two characters who don’t know each other well, interacting in basically one location: a Phoenix backyard at night, a truck in a parking lot near the fairgrounds, and outside an airport terminal in Seattle. The action in each is compressed but the feeling is no less than in those stories sprawling through time or containing more moving parts. These stories resonate, doing exactly what they need to, underscoring again what we all know: everyone suffers. Seeing that suffering play out in frustrating, lonely ways, as we see here, is affecting.

As someone who struggles to put together a story collection that resonates and feels honest and respectful to the characters while still standing as a cohesive whole, I read Chancellor’s collection with admiration. The care with which she creates these seemingly ordinary lives is evident. She lets her characters live and insists that we care about them. And we do.

About the Reviewer

Corey Campbell’s fiction has appeared in Gettysburg Review, Colorado Review, the Rattling Wall, Necessary Fiction, Jabberwock Review, and Anderbo, among other publications. A PhD student in creative writing at the University of Houston and graduate of the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers, she has received support from Inprint, Sewanee, and the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. She's a contributing editor for the journal Waxwing, now completing her first collection of stories.