Book Review

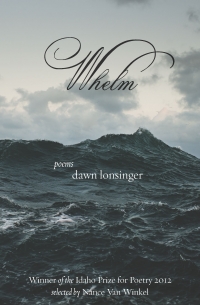

Dawn Lonsinger’s new book Whelm was the recipient of Lost Horse Press’s 2012 Idaho Prize in Poetry. It seems somehow proper, if not ironic, for a book so concerned with the abrasive effects of large bodies of water to win an award from such a landlocked state.

Dawn Lonsinger’s new book Whelm was the recipient of Lost Horse Press’s 2012 Idaho Prize in Poetry. It seems somehow proper, if not ironic, for a book so concerned with the abrasive effects of large bodies of water to win an award from such a landlocked state.

Near the end of this collection of poems she writes: “Love, do not turn blindly from evidence—there / it is—time as obvious oblivion … and repair.” The lines speak of the evidence left after a flood, echoing the book’s title, which is an archaic word that means to engulf or submerge. The poems themselves are a sort of evidential record of a life in which the figurative flood of the present moment pushes violently through the senses, leaving the detritus of relationships and unfinished identity floating in each line’s wake. For such a slim volume, Whelm is exhaustive in its cataloging of subtle observations. There are indeed some fine lines. From the poem, “Fall of Falling” come descriptions of harvest, pumpkin fibers between fingers, and people carrying corn that vanishes as time makes each moment disappear. These daily observations of agriculture assume mythic significance at the poem’s end:

Time is a tease, a tramp, a bully.

Time with its mouthful of dirt, with its hands

up our skirts. There are not enough Eves—knees

ground into the grit of the evermore sophisticated

garden—to devour the evidence.

In a book that privileges the view of each poem as part of a body of evidence, the above lines rewrite Eve’s role as the initiator of humanity’s fall, replacing that narrative with one of preservation—she is in charge of preserving traces of the individual who is eventually erased by the oceanic universe in which that individual resides. Throughout Whelm, these traces are numerous:

Through the kitchen window, I see an ATM

floating by, ether locked inside it, wet.

Somehow, through the instantaneous, beyond the now

Folded garage door, I hear a car pull into the ocean

The figure of the flood is often recognized by the objects it disrupts or disperses. But throughout the poems, these traces exist to be obliterated and reformed into new ones; the poems seek a sort of cataloging of flotsam contrasted with musings on the uneasy subjectivity that such cataloging makes visible. The poems keep these concerns about visibility and interiority in constant tension.

This tendency brings me to my only bone of contention with the book. It can be hard to render inside the reader’s skull the sheer number of images implied by many of the lines:

they can hear glaciers

tipping, water rising, maybe

the ovary-nouns by their own de-

vice map the water in

our bodies dispersing like shrapnel

But this is a minor issue in light of the book’s determination to overwhelm. Underlying such images is the figure of the individual trying to steel itself against the flood of the objective world at one moment, or against a flood of memory the next. The self in the poem is often presented in a contentious relationship to the inanimate world (“the topiary brain—scissored / by shadows”), and the tension between those two elements leads the book to turn inward, to investigate the inanimate elements that make up the subjective self. In the poem, “The Case of Lydia,” Lonsinger begins:

Lydia treasures looking

out from within display

cases, tenderly

climbs inside,

a fawn beside

mannequins

Lydia crawls inside the public aspect of the self, finding her “self” transformed into a display case for “real” objects, treasures that define her being. This mechanism is echoed several times in the book; in another poem, Lonsinger writes of “our cabinets of tissue.” This confusion between self and object, between the verifiable and the subjective verifier is measured throughout the book by the natural lights that shine on it. In the collection’s first poem, Lonsinger writes that “What glistened overwhelmed us.” And the moon rests kindly on the detritus of each observer’s life, whether or not that life conveys beauty or horror:

The moon licks one thing, lacquers another

is powerfully soft-spoken, turns heads of

lettuce porcelain

and sometimes within the moon’s bone china

dogs pierce the dome of darkness with a howl.

There are many things glimmering within the pages of Whelm, and many things in which to delight. Within its catalogs of the miscellaneous world, the book finds a cataloging of an observer always in danger of being swept away by things observed. These poems signify a constant flood, asking us to “feel the weight of its accumulated utterances” in what we try to keep.

About the Reviewer

Lincoln Greenhaw holds an MFA in poetry from Colorado State University. He lives in Denver and teaches creative writing at the Jefferson County Open School.