Book Review

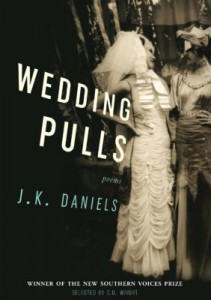

The poems in Wedding Pulls are energetic in language, theme, and form, marking both a fulfillment and promising debut. The late C. D. Wright selected it for the New Southern Voices Poetry Book Award, specifically noting that Wedding Pulls sought “a stricter ardor: being choosey with words. . . . Being particular about how the words rub or thwack against one another. . . . How a sentence is trimmed.” Brimming with characters, the poems are not narrative but tightly sprung lyrics whose wording reveals by doubling meaning and by doubling back to correct or redirect what’s been declared. Even the title, Wedding Pulls, plays on ambiguity. Mostly, it refers to the Victorian charms baked into wedding cakes or hidden in frosting. This increasingly popular bridal ritual foretells one’s love prospects. The title is also a sentence, declaring that marriage attracts, but the word “pulls” also implies “apart.” Through Daniels’s use of rich language and persona the collection is a restless inquiry into the meaning of marriage and family—presented in three sections.

The poems in Wedding Pulls are energetic in language, theme, and form, marking both a fulfillment and promising debut. The late C. D. Wright selected it for the New Southern Voices Poetry Book Award, specifically noting that Wedding Pulls sought “a stricter ardor: being choosey with words. . . . Being particular about how the words rub or thwack against one another. . . . How a sentence is trimmed.” Brimming with characters, the poems are not narrative but tightly sprung lyrics whose wording reveals by doubling meaning and by doubling back to correct or redirect what’s been declared. Even the title, Wedding Pulls, plays on ambiguity. Mostly, it refers to the Victorian charms baked into wedding cakes or hidden in frosting. This increasingly popular bridal ritual foretells one’s love prospects. The title is also a sentence, declaring that marriage attracts, but the word “pulls” also implies “apart.” Through Daniels’s use of rich language and persona the collection is a restless inquiry into the meaning of marriage and family—presented in three sections.

Each section is named for a different wedding pull. The first, entitled “Thimble,” refers to pulling a thimble from a wedding cake meaning that person will stay a bachelor or “old maid,” and the poems deal with the tempestuous search for love. The second section is named “Ring,” which foretells marriage, but the poems are not happily-ever-after. Finally, “Anchor” is the sign of hope, but it can also indicate being set adrift. Even this structure is ambiguous; the title poem both presents and questions these meanings. In it, the thimble is explained as “married never,” but another voice in the poem contradicts this, saying, “that’s not a thimble it’s a cup buy me a drink love.” The indeterminate nature of the symbols themselves demonstrates one kind of restlessness in Wedding Pulls while the polyphonic nature of this poem without context along with its lack of punctuation demonstrates another.

From the first poem, the pull of wedding, both as joining in love and in marriage, is ambivalent. The front piece, “On St. Charles Avenue” is set at a wedding. “Rosalind and her new husband enter,” but later, “she kisses you in the bathroom / lips the raw pink of carved beef.” This image—and situation—is unsettling in its vividness and mixed messages. In the next poem, “On Esplanade Avenue,” the section’s theme is stated: “you did not want to be a bride” but wanted the bride. Desire for communion is frustrated not only by being unrequited but by convention. In this way, the speaker demonstrates “multiple models of doubt.” Maybe the doubt is fueled by the tension of same-sex attraction in a social situation that denies it. Or perhaps it arises from a more basic masking of one’s identity. Either way, situations are pitched at the verge of such lyrical tension that speakers sometimes double up words, as if doubting their accuracy. For example, in “On Esplanade Avenue,” the speaker expresses longing for Rosalind who “might splint your sprained fingers but won’t accept their supplications” and then says, “Dieux not deux say I know no.” When knowledge is also denial, emotions are pent-up. Other times, a speaker distinguishes one word from another, mixing precision with a different kind of disclosure. In “As Thomas, Doubting,” the apostle who said he wouldn’t believe in the resurrection until he touched Jesus’ wounds observes that Mary has been “touched / too much.” This could be both a judgment that she is “touched,” as in crazy, but also too intimate with the savior, especially when he jealously states, “he kissed her on the mouth.” As if correcting these thoughts, Jesus says to him, “Thomas . . . you know / the difference between tender and tenderness.” Through these methods, Daniels evokes ambivalence about a loving communion.

Unprepared for the complexities of love, each speaker pursues an appropriate place in life. Given our matchmaking obsessions, marriage seems to be that place, but the second section, “Ring,” denies such hope. The opening, self-contradicting prose poem “Wedding Pulls” ends, “anchors aweigh my dear the anchor’s hope if you pull it you’ll be adrift so there.” Is one adrift when one pulls up the anchor, as in losing hope, or is the speaker cynically declaring that if one pulls the hope charm from the wedding cake, they’re set adrift?

From wedding to consummation the section advances to “As Eve,” and the ultimate first-time-for-sex story from Genesis. Here’s the bleak ending:

He entreated. He entered. And I was

the epithet, the epitaph, the epilogue

and then the exit. We existed (or at least I thought we did).

What a difference a day and an s, well placed, make.

From this inauspicious beginning of the union, the sequence goes from “Multiply” to “Divide” and into further unraveling. In the prose poem “Physiognomy” the speaker admits that “yes I don’t always get my way let’s call that strength of character moral fortitude but what do we do about your eyes in someone else’s face let’s not call it infidelity.” This is a kind of masking, like creating a persona (in “As Eve” and many others) or using “you” as an oblique “I” (in “On St. Charles Avenue”). These methods all reveal as they obscure. In this case, naming what we should not call it (“infidelity”) actually invokes and emphasizes the idea.

All these techniques operate in “What Have You Gone and Done,” a poem where the speaker uses metaphor to disclose and make a reckoning. In the first part, the scene is rendered with all the wordplay and deftness of language we’ve seen, mixing the erotic intimacy with cold metal division:

I leaned against the smelted grate, she kneeled

on the concrete:

we unsoldered the iron gate

of mate and merge, her mouth

on the verge of my median, that short

weave. She drove

I rode

the trolley home.

Not trolley, streetcar.

Here sexual union and a parting of the ways are devoid of relational detail. And the speaker responds by trying to get the details, the language, exactly right—correcting the means of transportation, as if that were the central issue. However, instead of getting to the nub of the relational dynamics, the speaker dodges and evades. These continue in the middle section:

I can’t say

I didn’t because I did.

I won’t say

what will be will be

after three cheap drinks

under the green awnings of Que Sera—

Not median, neutral ground.

Is this a one-night stand, anonymous sex outside a bar? Is the speaker accepting herself by accepting the love of another woman, making her body no longer contested but “neutral ground?” The final section resolves into openness and a sexual pun:

What’s done is done. This

is my stop: neutral

ground, avenue, eight blocks

of cracked sidewalk,

an iron gate, unlocked.

This is where I get off.

Emphasizing neutrality makes the poem a statement, but not a romantic one. It claims one’s sexuality, but seems to still be searching for relationship with another.

The search for true communion is, at root, also a search for identity. And those roots begin amid the complexities and complicities of our families of origin. The poems of the last section, “Anchor,” reflect the dual nature of the self-claiming process. This doubling is shown in the speaker’s confession at the end of “If You See Something, Say Something:” “I am, as you have always found me, wanting.” The word “wanting” conveys both the unending nature of desire and the perpetual feeling of never quite measuring up. This legacy of feeling inadequate starts in the first poem of the section, “Bent She Is,” where the speaker ruefully states, “I wish / I could have been a better child not afraid of everything.” As we search for our true selves, it’s as if we are that optical illusion of the young woman and the old hag, an image used to start “In Waiting.” Our dual sense of self may sprout from the binary choices given to many of us about gender and marriage (though that is loosening).

Altogether, Wedding Pulls points to the difficult process of self-claiming. By refracting the narratives through masks and voice, J. K. Daniels achieves something more coherent than the story of what happened. Even so, while coherence is achieved, resolution is not. It’s as if the book unfolds a story in reverse chronological order, from the contemporary wedding scene with Rosalind back through time to the roots of family and identity, which is a search for ghosts amid ghosts. And yet, the pull to understand the past and to use that understanding to create a viable future is the process of unifying of one’s own disparate elements. It’s the internal wedding, and the pull toward wholeness is powerful. And, as this book affirms, it is necessary.

About the Reviewer

Edward A. Dougherty is author of several collections of poetry, most recently Grace Street (2016, Cayuga Lake Books) and Everyday Objects (2015, Plain View). He teaches at Corning Community College.