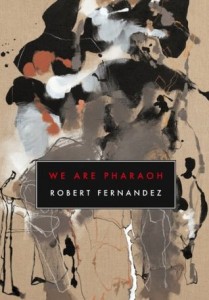

Book Review

Robert Fernandez’s ambitious debut, We Are Pharaoh, asks its reader to begin at the “billowing page,” a blank space of “intersecting possibilities.” The conjured image is a sort of endless paper sea, each line a current of images intended to flood our sensibilities—“the flesh calls back its bulls, the divers arrange themselves, occur as gods (loa) occur, that is, pliant: beds of mushrooms (pendentives) intersected by light.” As the poem’s title, “Polyhedron,” would suggest, Fernandez presents the reader with a figure possessing many faces: as we wind our way through a stream of images, the reader accesses a place of endless referentiality, suspending all expectation of narrative. Fernandez creates an experience akin to the headspace one enters when entering an art museum—a space dense with vision.

Robert Fernandez’s ambitious debut, We Are Pharaoh, asks its reader to begin at the “billowing page,” a blank space of “intersecting possibilities.” The conjured image is a sort of endless paper sea, each line a current of images intended to flood our sensibilities—“the flesh calls back its bulls, the divers arrange themselves, occur as gods (loa) occur, that is, pliant: beds of mushrooms (pendentives) intersected by light.” As the poem’s title, “Polyhedron,” would suggest, Fernandez presents the reader with a figure possessing many faces: as we wind our way through a stream of images, the reader accesses a place of endless referentiality, suspending all expectation of narrative. Fernandez creates an experience akin to the headspace one enters when entering an art museum—a space dense with vision.

Within the first few pages, the reader collides with what Fernandez calls “bacchanals of vision,” or prophetic utterances melding the real with the surreal, the contemporary with the ancient, the celestial with the mundane, the violent with the erotic. This kind of chaotic landscape, rife with color, violence, and urge, is harnessed by a sense of the visual—“Van Gogh paints a bouquet of pistols,” Velasquez sees a lakewater eye “rising into itself.” Through visual references, as well as pop-cultural ones, the reader engages in an act of creation—the reader becomes the artist, equipped with the tools and colors of the lyric to compress the drama of human history into the space of a book.

Fernandez conjures the entire history of lyric poetry and manipulates its potency to address the vastness and confusion of our age. The result is a challenging collage of amped-up lyricism, whose very definition is celebrated as much as it is interrogated and challenged: image-dense moments are interrupted startlingly with others. Just as viewers walking through a museum take in one moment of beauty in the same step as they take in another, all here is fleetingly explored as images are swept up in a tremendous wave of visual momentum. Fernandez’s lyric embraces the expansiveness of our world through the power of image, capturing the endlessly referential nature of the postmodern condition through the evolution of human vision. The ancient pushes up against the modern uselessly, deconstructing the linear so that time becomes strangely all-encompassing. Throughout the book, the lines lasso the ancient and yank it into the contemporary; coliseums groan their heft into the tropicalia of Miami; we are asked to consider Dionysus as much as Mike Tyson. This suspension of time allows Fernandez to lead the reader through discrete moments that mimic the experience of viewing art, the language itself performing a kind of sensual overload. Manipulating language as a painter manipulates a brush—melding color and texture through the visual field—Fernandez too constructs the “billowing page” as a field where all-time occurs simultaneously. He writes in “Emergence”:

If historical time is a tract of territories, like a field with various plots in rotation, and if each plot is an epoch of human history, say that we are coming out of the terrain of The Grand Tour, say that we have passed from the epochs of corn and wheat and entered the Epoch of the Radish. . . . A conceptualization of linear time as a splashing away and of a pushing forward onto a new barge that has miraculously offered itself up—La Muerte de Dios.

These lines establish the role of the collection, where all-time is visible at once. The viewer can begin at any epoch and move through eras at will. Fernandez harnesses the linear nature of reading—left to right, top to bottom—as if to mimic the linear passage of time—then to now, present to future—and manipulates it so that readers are able to experience this temporal dissonance as they move through the page. The effect is cacophonous as much as it is harmonious, “like a lattice of metaphysics.” We are pulled singularly through the many strands of time simultaneously, combing through the text as if through tangled hair.

But despite the expansiveness of Pharaoh’s scope, we are asked to delve deeper still into the possibilities of vision. Just as we are bounding across dreamy erotic landscapes of the body, we land in the viscous color of a Miró, the celestial spaces of Venus and Adonis, the wilderness of the Hyena Men from the photographs of Pieter Hugo. Fernandez renders the physical through the imagined, creating an ekphrastic feedback loop that performs the mimetic qualities of art through language, as in “Flowerheads”:

III.

Boom. Gainsay death metal is a window, ram’s-horn ripple. RZA shaved the track, niggaz caught razor bumps. Ascyltus: “To sell ’em, piece by piece, brick by brick, a catch!” Encolpius: “Twice the street value . . .” Homage gainsays a death-work of preterit lexicons. Tramlines etched adept, colossal rounded patterns.

The references to visual art act as a layer placed over the body of the book—a sort of veil, obscuring as much as revealing what it can about the text. Fernandez is interested in the potential of perception and how perception evolves contextually over time, often taking different shapes for different viewers, or in this case, readers. Fernandez asks his readers to approach the book with a new approach to the lyric—a form (if it is one) that prizes complexity over linearity, abundance over sturdiness. The effect can be confusing, maddening, baffling, but its intensity can’t be denied.

About the Reviewer

Vanessa Angelica Villarreal is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Colorado at Boulder, where she studies poetry and prose. She is the recipient of the Brian Lawrence Poetry Prize at the University of Houston, and her work has appeared in The Potomac Review.