Book Review

As a language virtually extinguished along with its speakers during the Second World War, all Yiddish literature bears great resemblance to eulogy. Yiddish books certainly exist as individual, standalone works of art, but as a group they are also powerful symbols of a world destroyed. So reading Yiddish literature today has the unique capacity to revive the people who once spoke the language, give them a new life, and allow the dead and their individual stories to stand in contrast to the anonymous wall of genocide.

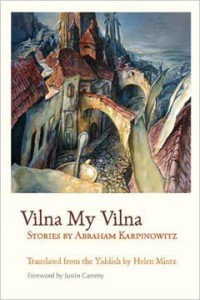

Abraham Karpinowitz’s collection of Yiddish stories, Vilna My Vilna, reminds us of this history and its unique cultural elements with a masterful and unerring sense of the liminal (even vanishing) status of Yiddish. His town, Vilna, now Vilnius, the capital city of Lithuania, was once a vibrant Jewish city were Yiddish played a prime role in both literature and life. Jews were a central part of the city for more than five hundred years, until the Germans exterminated most during World War II.

In the first story, “Vilna without Vilna,” the narrator returns to the city in 1989 for the first time since the war, only to find that “[a]bsolutely nothing remained.” But in his memories, every street corner and doorway is a reminder of a vanished Jewish world. The narrator’s memory places long-dead characters onto a strange gentile cityscape. This sense of discontinuity is jarring. The streets and buildings no longer align with memory—during the war they had “been mowed down like grass in a meadow . . . [and] [t]he new buildings don’t match their surroundings.” Vilna is Vilna—but erased of its Jewish past.

The stories wrestle with the intractable yet slippery line between reality and memory. In “The Amazing Theory of Prentsik the Shoemaker,” the main character experiments with crossbreeding animals to create a new kind of menagerie. Swayed by exotic scientific theories, Prentsik wants to teach God a lesson about beauty: “God himself would take notice. Prentsik argued that if the Creator wanted to, He could create animals as adorable as dolls. He even had the ability to reshape Prentsik himself so that one of his eyes would no longer be closer to his ear than to his nose.”

Of course, God does not change Prentsik’s appearance, and his experiments with beautifying the world’s creatures become literal monstrosities. In the end, Prentsik understands that “nature did indeed have its own laws . . . and his own life was controlled by a cruel law.”

Nature’s cruel law is also at play in the next story, “The Red Flag.” Abke—a well-known, petty Vilna thief—is punished for a moment of compassion. He feels sorry for a malnourished Jewish boy trying and failing to hang a Communist flag from a pole. Because “this is a Jewish child,” Abke hangs it himself and is promptly caught. He is accustomed to jail but has no experience as a political criminal. Unless he can prove his innocence to the anti-communist government of Poland, he will suffer for his show of Jewish solidarity.

In “Shibele’s Lottery Ticket,” two down-and-out musicians receive a ten-zloty handout from a famous pianist. Instead of using the money to buy new clothes or food, they purchase a lottery ticket. They win, but the ticket promptly disappears, and the entire Jewish community searches for it without success. Meanwhile, the two musicians fade away, falling into the cracks of obscurity, poverty, and exile as the lost ticket becomes a symbol for far greater catastrophes that await the Jews of Vilna.

In “The Folklorist,” Rubinshteyn ventures into the Vilna fish market to collect the sayings and curses of the fishwives for his research. He falls in love with a colorful fishmonger named Chana-Merka, and the two begin an unlikely love affair that briefly captivates all of Vilna. But it is not to be: with or without love, the folklorist and fishwife will share an equal place in death.

Karpinowitz’s fiction also explores Vilna’s vibrant Jewish criminal underworld, a lonely young woman trapped in a life of prostitution, and the colorful Yiddish theater. In the penultimate story, “Memories of a Decimated Theater Home,” the young narrator relates the highs and lows of his father’s theater. After all the drama and life he has witnessed, he asks:

What happened to that world? The Germans converted my father’s Folk Theater into a garage for military tanks. They tore down the balcony. Before they left the city in 1944, they destroyed the theater, tearing it down to the ground . . . He went to a mass grave at Ponar with his audience, the loyal Vilna theater.

In the final story, “Vilna, Vilna Our Native City,” the narrator attempts to disentangle his memories from nostalgia. He says that “[w]e should be careful not to idealize Vilna. . . . As well as light, there was plenty of shadow.” But Karpinowitz can never quite get away from painting a picture of Vilna as a Jewish paradise: “In Vilna, we lived a full-bodied Jewish life.” According to Karpinowitz’s fiction, in part because they were unaware of the coming storm: “We didn’t know that a day would come when we would be flung across the globe, forlorn and orphaned . . . and that of all of Vilna, only a pale memory would remain.”

Jewish Vilna is forever gone, but this translation of Vilna My Vilna does much to keep its pale memory alive. Helen Mintz renders Karpinowitz’s slangy, colloquial Yiddish into a lively and idiomatic English and graces both Karpinowitz’s stories, and even Jewish Vilna itself, with a second life.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his wife and two children and is currently at work on a book on Jewish religious recluses, a novel, and short stories.