Book Review

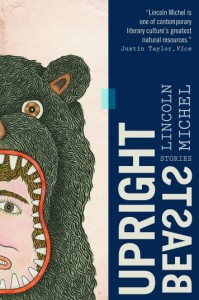

There are many ways to assemble and animate the flesh of those upright beasts called books. This is particularly true when dealing with short story collections, whose constituent parts (the stories) must somehow be fused into a viable creature. Sometimes the result is clean and lupine—think Alice Munro’s Runaway or Richard Ford’s Rock Springs, which achieve a sleek, forceful unity of subject, style, and tone. But Lincoln Michel, with his new collection, has produced a different animal completely: one made of mismatched limbs and patches of fur, with odd-numbered eyes and a hide seamed by hideous scars. It’s not immediately obvious what the method is behind this mad act of creation, but maybe that’s the secret to its vitality. There is a bold, unpremeditated feel to Upright Beasts, a debut whose great strength is a changeability that keeps the pages turning as it veers from lucidity to madness and back again.

There are many ways to assemble and animate the flesh of those upright beasts called books. This is particularly true when dealing with short story collections, whose constituent parts (the stories) must somehow be fused into a viable creature. Sometimes the result is clean and lupine—think Alice Munro’s Runaway or Richard Ford’s Rock Springs, which achieve a sleek, forceful unity of subject, style, and tone. But Lincoln Michel, with his new collection, has produced a different animal completely: one made of mismatched limbs and patches of fur, with odd-numbered eyes and a hide seamed by hideous scars. It’s not immediately obvious what the method is behind this mad act of creation, but maybe that’s the secret to its vitality. There is a bold, unpremeditated feel to Upright Beasts, a debut whose great strength is a changeability that keeps the pages turning as it veers from lucidity to madness and back again.

In twenty-five stories (twenty-six if you count an unusually haunting Note on the Type), Michel ventures through a tainted American landscape full of monsters, pitfalls, neglected gods, and robot butlers. The appeal here is in being disoriented, moving abruptly from one reality to another—even within the confines of a single piece. The slow dissolution of a marriage can, and will, be interrupted by episodes of paranoid delusion or paranormal fear. A story that begins as an Edith Wharton-like drama of sexual rivalry can transform smoothly into a spot-the-imposter murder tale. Michel tries on a variety of structures and genres, and in the process he lets some seriously wild animals out to play.

Take “Dark Air,” in which three young city-dwellers drive into the hills to “get a little . . . country air,” guided by a clickbait article: “Top 10 Secluded Spots for Selfies.” In addition to this (probably accurate) potshot at a generational subset that can’t go hiking without consulting Buzzfeed, Michel none-too-subtly introduces some love-triangle tension: while our narrator drives the car, his girlfriend Iris flirts with roommate Dolan, touching his arm and laughing at his inane remarks. Moments later the narrator imagines “the door popping open when we went around a sharp turn, then watching [Dolan] tumble down the cliff and disappear.”

Just as both narrator and reader settle in for what looks to be an ill-fated, somewhat laborious emotional excursion, all hell breaks loose. They run over a bizarre creature: “It looked like a crow, except the feathers had fallen off its back…the exposed skin was split in half by a row of translucent spikes.” The car smashes into a cliff face and is immediately swarmed by bees. (Iris’s automatic response is to begin snapping selfies.) But all this is only a prelude; our three intrepid hipsters are soon enmeshed in a full-fledged horror story involving extraterrestrial orbs and a family of backwoods psychics dining on “the flesh of the star-fallen.”

For all the sensationalism of this premise—and restraint is not Upright Beasts’ defining quality—there is nevertheless something understated about the way Michel handles it. Watch the narrator in “Dark Air” sum up his experience with dry humor and plainspoken language—he’s still reckoning with getting dumped by Iris as much as with the strange force that’s taken up residence inside him:

I’m not as angry as I used to be. When I get worked up, my head throbs, so I have to be calm and let things move through me. The eye on the back of my neck doesn’t look too much bigger, but it’s hard to tell. I wear a lot of turtlenecks.

Michel’s style is spare and conversational almost throughout, frequently employing somber first-person narration by ordinary people whose circumstances grow increasingly extraordinary. In fact, one could argue he hits his highest register in the acknowledgements, when he thanks “you, you vile, luminescent animal, sitting there with this book in your gnarled and sculpted hands.” But he does show a broader range on occasion. Some of the collection’s best pieces are its shortest—these display deft sensitivity alongside bursts of unhinged imagination.

“Little Girls by the Side of the Pool” is a standout, both convincing and fantastical, tender and alarming. Entirely dialogue, it begins with childish boasts: “My father is really good at tossing me into the water” and “My father once threw me like ten feet out of the water,” evolving into a mature, unsettling discourse on the oppressive physicality of a world filled with men:

“I hate all fathers. It is the way they touch you.”

“Their hands are swollen. When you are born they can carry you in their palm. You grow older and taller, and yet their hands never shrink. When one wraps around your shoulder, the weight immobilizes you.”

And later:

“Sometimes Jimmy takes me out of the water to a dark place behind the bushes, and he takes off his sunglasses . . . ”

“And these are the eyes you hate? The eyes that thin to the edge of a knife when he approaches?”

“No, it’s as if his eyes are clouds that have emptied themselves of rain…It’s the way he looks at me afterwards, in the light, with a great sadness . . . like a father.”

Michel gets obliquely political in another short piece, “What We Have Surmised about the John Adams Incarnation,” which has a far-future anthropologist lecturing on “the ‘Constitutional Pantheon’ of the United Statsian religion.” It’s a parody of the misguided way we often interpret ancient or aboriginal cultures, but at the same time perhaps not such an inaccurate description of our own national belief system:

The Founding Father, in this conception, was a shape-shifting and eternal god believed to have formed the nation by tearing apart fragments of the Life Tree . . . and regurgitating fifty large bark chunks into the sea to form the collected states.

Say what you will about this origin myth, it’s approximately as believable as the prospect of a Trump presidency. The story’s final note is sobering, and more than a bit diagnostic of the country’s current mental frailty: “It is important to remember that the early United Statsians were a frightened but proud people . . . the world was as confusing and painful a place to them as it is to us now.”

Confusing and painful it is, full of monsters real and imagined, those that we’ve created and those that have waited for us since time immemorial. Lincoln Michel has done us a favor by rounding some of them up and giving us a motley menagerie to examine—with the understanding that we can’t hold them for long, and there are a whole lot more still out there to find.

About the Reviewer

Benjamin T. Miller is a writer whose fiction and essays have appeared in Zyzzyva, Santa Monica Review, Epiphany, and others. He earned his MFA from UC Irvine, and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. www.benmillerwriter.com