Book Review

The opening lines of “This Bridge Across,” the first poem in Turning into Dwelling, introduce us to a flow characteristic of Christopher Gilbert’s thought and voice:

A moment comes to me

and it’s a lot like the dead

who get in the way sometimes

hanging around, with their ranks

growing bigger by the second

and the game of tag they play

claiming whoever happens by.

I try to put them off

Though not his most dramatic writing, it gives a sense of an ease of movement and association, even playfulness in his tone that can thread together an yet undefined moment with the dead and their game of tag getting in the way. These lines also introduce one of his preoccupations—the moment, how he’s at once rooted in but pushing beyond a given moment. In the case of this poem, ancestry creates something larger than the present and himself, a way of finding himself in his ancestors. In Gilbert’s words, “each moment is a boundary / I will throw this bridge across.”

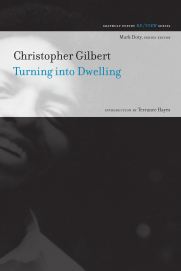

Turning into Dwelling, published in 2015 by Graywolf, reprints Gilbert’s Walt Whitman Award-winning debut Across the Mutual Landscape, originally published in 1984, followed by a manuscript of later work which, with the exception of individual poems, hasn’t been published before. Gilbert died in 2007 of a hereditary kidney disease.

One of many relationships between Gilbert and boundaries is illustrated in the aptly titled poem “Pushing,” showing us a young Gilbert and his brother testing the boundaries of a grocery store owner who, likely because they’re black, has an eye on them. The owner tells them, “buy something or else you got to leave,” though they repeatedly return to the store to “try his nerve again, ” often looking without buying, which Gilbert explains to his brother by saying, “Some things you do because you want to. / Some things you do because you can’t.”

Many of his poems don’t just push boundaries of time, place, race, and self, but seem to simply blow past them through their breadth of vision and striking diction. “Exactly Passing Through (Horn Player)” centered around hearing a horn player on a corner, ends with:

our attention is blue-insistent and forward-looking,

a kind of sky which has gained a way of being inside

its wholeness—not ideal nor abstract but exactly

what is happening.

Along with a striving for wholeness, the relationship of individuals to the sky comes up often, including in “The Directions,” about a dancer:

The sky has always wanted something

to belong to it. Its backward gravity

pulls the dancer’s shape, and he flies

upward in himself airy in the mind.

And this symbiosis between dancer and sky, individual and surroundings, which in turn pushes toward a new wholeness, shows up expressed as direct statement in “Listening to Monk’s Mysterioso I Remember Braiding My Sisters’ Hair,” where he writes:

this coming into newness, this dis-

continuous mind in you looking up, finding

an otherness which trusts what you’ll become—

What I admire about Gilbert also challenges my conventional conceptions about good writing. When he turns his eye toward what’s continuous in the discontinuous, Gilbert swims against the current of contemporary aesthetics, which emphasizes breaking the narrative and looking for what’s discontinuous among the continuous. Both approaches can juxtapose disparate words, ideas, and experience, so they also have potential to create energy and insight—in Gilbert’s case, to cause startling reorientations of vision. Both can be honest. But Gilbert’s approach I think is far rarer and harder to pull off, in part because I don’t think I’m alone in being used to and looking for writing that creates energy through expressing feelings of disorientation and disconnection rather than connection.

Proclamations about “finding an otherness” out of context feel like telling rather than showing, or making sweeping generalizations. In this case the “otherness” he speaks of is his sisters inviting him to learn how to braid their hair, the comb pulled through the “knots and their little Vaseline,” specifics that give this poem and others—including the broader, sweeping statements—the sense that they’re honest, urgent expressions of their moments.

His later, previously unpublished poems continue similar themes, including references to music, improvising, and one’s life being an improvisation. In “Chris Gilbert: An Improvisation” we read:

I feel a gathering possibility passing from temporary

articulation to articulation the way the horizon

arises in the sun as a series of evident illuminations

The later work also offers a number of poems about plain, old-fashioned feeling out of place as a black man “playing cultural solitaire,” poems like “Pleasant Street,” “The ‘The,’” and “Tourist.” In the opening of “The ‘The,’” Gilbert stands outside a library with an expired ID card:

locked outside the language

through which I am

the things I mean.

And the long poem “Into the Into” has enough to engage with and think about that it deserves a review of its own. The addition of this later manuscript adds more layers of emotional depth and rounds out what was an extraordinary first contribution.

His soaring lines hold together because of his individual voice and vision certainly, and because they’re rooted in the world. Gilbert’s presence is like the kite-flyer in one of his poems, his feet planted while his mind races ahead, reaching. The loss would be ours if we aren’t reading and discussing him years from now.

About the Reviewer

Brian Satrom lives and works in Minneapolis. His poetry has appeared in journals like Knockout, TAB, and Poetry Northwest, and was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize.