Book Review

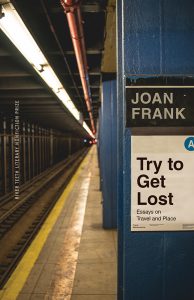

In “Cave of the Iron Door,” the rich and deeply moving essay at the heart of Joan Frank’s recent collection Try to Get Lost, the author stages a visit to her childhood hometown as a way to explore how our memories become rooted in particular places, even as those places continue to evolve without us. The essay first reads linearly as Frank arrives back in Arizona, but then, just a few pages in, she includes a remarkable montage of listed memories—this is an author who is very fond of lists—that pivots the narration immediately back to her childhood, from which point she proceeds to uncover hard truths about her family and its ultimate disintegration.

Frank pays affecting tribute to the lives of her mother and sister, both now gone, through the lens of place. And as the essay ends, she recalls visiting this same town years ago with her sister, before this present trip. They knock on the door of their childhood home, and because of the generosity of the strangers who now live there, they are allowed inside to explore. And when she finds herself standing in the bedroom where she had once discovered her mother’s body, dead from a barbiturate overdose when Frank was just a child, she’s shocked to see a baby sleeping quietly within. “New life could continue to gather itself, with normal ravenous fury, in the space where prior life had stopped,” she writes, “The space made no objection—exuded no residual poison.” And in this way, she concludes that we are the ones who give places their agency, their ability to affect us so deeply—indeed, to change us forever.

The subtitle of Try to Get Lost is “Essays on Travel and Place,” but Frank evades defining these words too plainly, allowing their meanings to complicate rather than interpret the pieces collaged together within the book’s pages. These conversational yet startlingly intellectual essays circle around notions of travel and place in order to make broader claims about our relationships with our own personal histories. There’s a range of place-specific essays focusing on both the merits and shortcomings of postcard-ready travel spots, such as her beloved France, a setting which provides an occasion to ruminate about how we come to possess the destinations we treasure. She turns her eye to England, too, which she writes about scathingly for its brutal class divisions, one’s “place” in that country less a physical location than a social standing. And while an essay about Florence can seem perhaps too much a catalogue of things to do and see, rather than a furthering of the ideas that simmer so intelligently elsewhere about the act of looking at all, these essays soar when the writer as thinker and the writer as traveler—in the sense of a person moving deliberately through the world—most wholly converge.

Similar to “Cave of the Iron Door,” another essay that combines travelogue with personal history in striking ways is “Little Traffic Light Men,” also about a return to a particular place after a long time away—in this case, Germany. Frank returns to the country twenty-two years after a previous visit shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and she’s surprised by her perception of a country that has, at least from her vantage point, successfully shed the darkness of its collective history. A childhood fear of annihilation as a young Jewish girl, after having watched the film adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank with her sister, had caused her to internalize the film’s wartime iconography and to later project her sense of horror onto its actual setting in person. But now she struggles to find evidence of what she’d always expected to see.

“But surfaces can mislead, or at least rarely tell the whole story,” she continues, before discussing an article about a type of group therapy designed to help Germans “exorcize the abiding internal connection with all the history [she’d] so blithely assumed them safely past.” And to illustrate how our buried traumas are always simmering just below the surface of our outwardly collected selves, she describes a moment near the end of her trip when she loses a museum pass in Berlin. Her husband is briefly angry with her, and suddenly her veneer of calm completely dissolves as she faces head-on a fact that has been only barely stamped down for the entire trip: her grief about the recent death of her sister. Only when she later watches a video at the museum depicting in montage the entirety of human history does her grieving mind finally settle, as she recognizes herself and her family as just one small part of “the continuum of human struggle, of atrocity, joy, agony and wonder.”

The personal is resurrected in the context of place; the buried thing comes alive in most unexpected ways. Elsewhere in Try to Get Lost, when writing about the shock of mortality—her own and that of others—Frank wonders whether “the fact of Place feels intimately bound up with the whole business—this acute, spreading recognition of a finite self, operating so briefly in time and place.” These essays cohere most completely when framed as an effort to witness both the outside world and the inner workings of an intricately coiled self, earnestly trying to make meaning from evidence both sporadic and fleeting. And the collection is understood most intimately when considering the whole idea of travel as a metaphor for life itself.

Frank’s early claim in Try to Get Lost about travel as “vital to the making of a moral citizen” is well-argued, but these essays are most successful when the writing is closest to home. Indeed, the final essay in the collection, “Coda: I See a Long Journey,” literally narrates a drive home, as though this is where we’ve been headed all along—home as an ending. On the drive, while listening to a Rachmaninoff concerto, Frank experiences the sudden procession in her mind of a series of intensely rendered memories from every period throughout her richly lived life, and she leaves readers with a directive to live purposefully—the “lost” of her title a sort of radical acceptance of the unknown—as well as the promise of an ending, mortality ultimately setting the terms of the longest journey of all. “[T]here is always, in setting out, the dream of the thing,” she writes. “In time, there is but the thing itself.”

About the Reviewer

Richard Scott Larson holds an MFA from New York University. His creative and critical work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Chicago Review of Books, Electric Literature, Slant, Joyland, Hobart, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and other venues. His writing has also recently earned notice in the Best American Essays series, and he has recently been awarded fellowships and residencies from the Vermont Studio Center, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, and the Millay Colony for the Arts. Born and raised in the suburbs of St. Louis, Missouri, he now lives in Brooklyn and works for the Expository Writing Program at NYU.