Book Review

Summer, 1983. Thea—short for Dorothea—Knox has just graduated from college, just shorn her hair, just adopted an abandoned dog she names Josie and is driving her best friend’s Buick Skylark across the country from California to New York State. As she approaches the fictional college town of Merdale, Kansas, a storm blackens the sky. Lightning zig-zags, hail the size of chestnuts pounds the Skylark, curtains of rain descend. And then, miraculously, the storm breaks just before she arrives in Merdale: “The road was silver, shiny, as if made of mercury. The wet grasses on either side glittered gold and green in the watercolor light. The sky was violet.” We must be in Kansas.

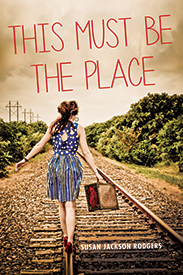

Although there are few overt references to the Wizard of Oz in Susan Jackson Rodgers’ This Must Be the Place, allusions to it abound: the road, the name Dorothea, and her little dog, too. Ruby red slippers become red Converse sneakers. The good witch of Merdale is Thea’s Aunt Wendy, who lives in a cornflower blue house fronted by a wildflower and prairie grass garden filled with garden gnomes; when Wendy kisses Thea’s forehead, Thea wants to wear the pink lipstick mark on her forehead like a charm. The Wicked Witch is a lawyer named Amira, who first appears in the novel as a “thing [that] seemed to shimmer. Ghost? Shape-shifter?” Like Almira Gulch, the Kansas-side villain of the Wizard of Oz film, Amira quickly finds her nemesis is a dog; Josie barks at Amira when she arrives and nips her finger. But what are we to make of this Dorothea’s unplanned sojourn in Kansas?

Thea describes her arrival in Merdale like this: “One of my English professors once said that there are only two stories in the world. Someone goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town. But that’s just the same plot from different viewpoints. I was the traveler, and the stranger.” In a 1987 op-ed in the New York Times, novelist and travel writer Mary Morris wrote that it was John Gardner who once said that there “only two plots in all of literature: you go on a journey, or the stranger comes to town.” Morris continues: “Since women, for so many years, were denied the journey, we were left with only one plot to our lives—to await the stranger. . . . Women’s literature, from Austen to Woolf, is mostly about waiting, usually for love.” By going on her own journey and arriving as a storm-tossed stranger in Kansas, Thea subverts both the Wizard of Oz and the traditional plotlines of women’s stories that Morris describes.

And yet, the subversion of traditional women’s literature may end there. The novel can’t seem to decide whether it is a journey story, a coming-of-age story, a murder mystery, a tragi-comedy of love errors, or a straight-up romance. Among the characters who move across the Merdale stage is Thea’s love interest Jimmy: white-blond handsome, kind, simultaneously a down-home Kansas farmer and a history professor. Then there is witchy Amira, Thea’s interfering rival who concocts drugged Jell-O shots for a party and may have had a hand in setting Jimmy’s home on fire. And there’s Thea’s employer Professor Pierce, a paraplegic psychologist in his fifties and wheelchair-bound voyeur for whom Thea is a willing participant in peep shows involving Thea, dressed in a French maid’s costume, flashing the Professor. Can we learn something from the novel’s characters about coming-of-age as a woman in the early 1980s?

Summer, 1982. As I read this novel during the fall of 2018, the nation collectively returned to the summer of ’82. Everyone, it seemed, was glued to coverage of Christine Blasey Ford and Brett Kavanaugh’s testimonies before the Senate Judiciary Committee and their recollections of that summer. As I both read and watched, I looked for connections between Thea’s recounting of her summer of ’83 and what those testimonies might tell us about how women and men’s stories of the early ’80s were told, listened and responded to. There’s no mention of boofing or devil’s triangles or sexual assaults in This Must Be the Place, although there are boozy parties and those spiked Jell-O shots brewed up by Amira. But Jimmy still says things like, “’You can help cook if you want, or just stand in the kitchen looking pretty.’” And Thea still responds with: “You sure are a smooth talker.” At least Jimmy cooks, I suppose. Despite a female protagonist who both goes on a journey and is the stranger in town, the story leaves its heroine waiting. After Jimmy and Thea have sex for the first time, she waits for him to say something. “[M]ostly,” she says, “I was waiting because that’s how I was back then. I had to know what he was feeling before I could know what I was supposed to feel.” Here, the heroine is not only waiting for love but waiting for a man to tell her his version of the story so that she knows how she is “supposed to feel.” Perhaps this reveals more about women’s coming-of-age in the early ’80s than Thea intends. The reader is left with the hope that by identifying that instinct to wait as belonging to “back then,” Thea has since moved on from the young woman she was in 1983 and has recognized that this is her story to tell, her love to describe, and her complicated place called home to find.

Ultimately it is the novel’s repeated return to the search for home that seems to be at its core. An epigraph to Part II reminds us that the book’s title stems from the Talking Heads song “This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)”—released in November 1983, the season after this story takes place—and that two of the song’s lines are: “Home is where I want to be/ But I guess I’m already there.” Rodgers isn’t the only novelist (or memoirist or filmmaker) to be inspired to use it as a title. Three other novels entitled This Must Be the Place predate hers: Anna Winger’s 2008 novel follows an American named Hope who tries to make Berlin a home after the trauma of New York City post-9/11; the home in Kate Racculia’s 2010 novel is a boarding house in New York State; Maggie O’Farrell’s 2016 novel is about an internationally famous actress who decides to disappear from public view by making her home in rural County Donegal, Ireland. The question of what makes us feel we are truly at home is a universal one, one we all wrestle with. “There’s no place like home,” says Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz and returns to Kansas. In Rodgers’ version of This Must Be the Place, Thea’s home for the summer of 1983 is Kansas; there may be no place like it, but whether it is the home where Thea wants to be is a question she must answer for herself.

About the Reviewer

Lisa Harries Schumann lives outside Boston and is, among other things, a translator from German to English, working on texts whose subjects range from penguins to poems by Bertolt Brecht and radio shows by the cultural critic Walter Benjamin and the radio pioneer Hans Flesch.