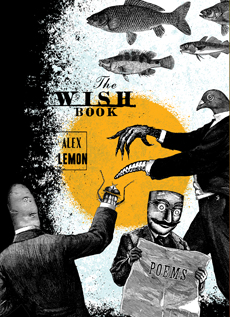

Book Review

In his introductory essay to the 1998 Best American Poetry, Robert Bly states that to sound authentic, a writer must use the language from the decade in which he or she was born. But how does a poet do that when language has become a pragmatic tool, used now to convince us that sponges can be both new and awesome, that the McRib is amazing, sublime, surreal? Lemon’s new book faces this challenge by stealing phrases from cashiers, billboards, movie trailers, television shows, the radio—anywhere, really, where our language has gone over to—let’s just say it—the dark side. And then he gives them back to us, brand-spanking new:

In his introductory essay to the 1998 Best American Poetry, Robert Bly states that to sound authentic, a writer must use the language from the decade in which he or she was born. But how does a poet do that when language has become a pragmatic tool, used now to convince us that sponges can be both new and awesome, that the McRib is amazing, sublime, surreal? Lemon’s new book faces this challenge by stealing phrases from cashiers, billboards, movie trailers, television shows, the radio—anywhere, really, where our language has gone over to—let’s just say it—the dark side. And then he gives them back to us, brand-spanking new:

Soon, no one will want unlimited

Texts because it will be known—

This here right now, this,

Exactly what you mean—

Is brought to you by

Every second that happens

Hereafter & how the sunrise

Holds your closed eyes.

How many times do we hear, “brought to you by” in a single day? How often do we actually listen to it, though? In the poem, we hear it fresh; all of its absurdity comes dripping out, and the speaker’s right there to play with it, just as he does with other, less commercially focused phrases:

I got to have whip-

Smart & boom

& no one’s

Getting any—

Midnight’s jiggling

Light says

Last call

& doomsday

“Last calls,” “getting any”—these are pub phrases, the words of friends with whom rapport has passed into the familiar. However in the context of a poem, with line breaks, enjambments, attention to technique, these phrases sound shockingly sober. Lemon writes from the place where language is a fascinating game and poetry is a joyful experience shared between friends.

The book reads quickly, in part due to the speaker’s confidence in sharing his worldview without hesitation or apology. Except for a handful of poems, the book exists heavily in the world of the “I”:

I’m a big jellyfish,

All grown-assed—I can

admit it now

And when the poems don’t exist in the first person, they rely on the second person, but feel like the “you” might as well be the “I” from earlier:

It will be last call. It will be the most

Perfect midnight in your life.

Right then, when it all seems like gravy,

Your dreams will shatter

& turn on you.

I remember my first time reading Ashbery’s “The Instruction Manual” and getting legitimately upset when he switched from “I” to “you” in the middle of the poem. (I wasn’t the one goofing off when I should’ve finished my assignment, and I didn’t appreciate the suggestion that I had slacked off, too.) With Lemon’s work, I feel accepted by and acceptable to the “you” in the poems. I’m not implicated by anything; I’m included. This counters the self-referential nature of the poems and saves them from becoming solipsistic and myopic by extending the focus of the poetry in a clever and sidelong manner.

In a lyric, first-person state, anything can happen. Because the poems don’t follow a strict narrative, the speaker has no reason to make sense of everything. We can have, as Lowell called them, the unexplainable details. These can lend the poems a sense of mystery, a sense of the unexpected. In the lyric state, nothing says you have to play in one particular way; nothing stands there to call out of bounds based on some preconceived storyline.

Two questions arise for me because of this freedom: 1) What does the poet gain by writing in a first-person lyric? and 2) What does the poet lose? In response to the first question, I believe that the poem “The Itching is Chronic” responds to this issue with much greater intelligence than any reviewer ever could:

Look: I can

Say the solar system is a fabric

Of hot dogs somersaulting

Through gaseous expansions

& make you think about it

For a second.

And then, for good measure, later in that same poem, he proves the point:

Let the record

Show I’ve cloned a human

In the upper right drawer

Of my desk.

Invention, creativity, alchemic lyric ability: that’s the advantage of writing in this lyrical, first-person model. He can create anything he wants, because that’s the power of language and the imagination. It’s exciting to see it used with intelligence and humor, but it can, at times—like any creature learning it has the power to create—become enamored with itself.

When he goes too far, the effect feels equivalent to a fire hose without a person guiding it: the sheer thrill of the water pumping through takes over the vessel and nobody knows who or what was supposed to get soaked.

Just five bucks & O my—

Welcome the razzle dazzle—

Parades, bobbing balloons

Granted, in context, these lines may turn out to be another reader’s favorite moment. But, for me, I felt gushed over by the language, the meaning drowned out by the spray.

The longer poems like “Disneyfication,” “Shake Down Machine,” and the entire third section, “Real-Live Bleeding,” didn’t work for me because of this effect. I find that Lemon’s style works better when the poems are short. After a while, I can’t take another drink.

In the end, what I love most about this book is how it drives itself and how it drives the reader to finish it. This is a book excited to exist, excited to play with the language, and joyful from the opening page to the end. Though many of the poems deal with death and dying, the real concern here is how every line has a charge to it and every phrase has a current running through it. And you can feel it positively humming when you pick it up off of the shelf and hand it over, as you will want to do, to the next person you see.

Published 5/5/2015

About the Reviewer

Patrick Whitfill has poems and reviews appearing or forthcoming in The Kenyon Review Online, Subtropics, The Journal, Mid-American Review, West Branch, 32 poems, and many other journals. Currently he lives in South Carolina, where he co-curates the New Southern Voices Reading Series.