Book Review

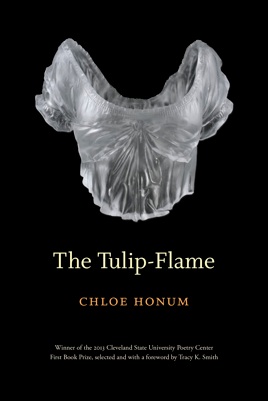

Chloe Honum’s The Tulip-Flame stretches eloquently across themes of love and loss and recovering from what we cannot control. The collection was selected by Tracy K. Smith as winner of the 2013 Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Contest. In this debut collection, the speaker is a ballerina—full of control and beauty, poise and restriction—who loses her mother, her romantic partner, and—for a time—her own identity.

Chloe Honum’s The Tulip-Flame stretches eloquently across themes of love and loss and recovering from what we cannot control. The collection was selected by Tracy K. Smith as winner of the 2013 Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Contest. In this debut collection, the speaker is a ballerina—full of control and beauty, poise and restriction—who loses her mother, her romantic partner, and—for a time—her own identity.

The opening poem delivers a jarring first line: “Mother tried to take her life.” Yet in this poem, the speaker details how life grows and expands during spring, how the garden blooms and birds take flight, even after the loss of a loved one. Some things, the speaker suggests, are like moonlight, “which has no pace to speak of” and has its own path outside of season, perhaps beyond reason.

The theme of seasons carries through not only the mother’s life and death, but also through the speaker’s relationship with ballet. In “Ballerina in Winter,” the speaker reflects on how “Through this season given to storms, I wake at dawn to practice.” In this prose poem, the speaker drifts delicately through an early morning dance session where she “drag[ged] aside living room chairs, like heavy dreams,” while the world outside her controlled environment is less rigid, less predictable: “Sometimes lightning slices the hills / straight through and doesn’t hit a nerve.” The outer world may not be as choreographed as the speaker’s moves, but the speaker is unnerved by the exterior chaos enveloping her practice. She is aware of what is outside her control, but poises herself against distraction by engaging in her ritualistic practice.

This desire for control proves ineffective as the speaker clings to her mother and urges her to live. As she sits at her mother’s bedside in “Visiting Hours,” the speaker urges the mother to want to live, to be happy that she is alive, though in her reflection the speaker realizes “My love was a knife / against her throat.” She must express her desires to her mother, but the speaker knows it is self-serving and a burden to the mother. The speaker can only control what is within her own power—dance. This acceptance is reiterated in the title poem from the first section, “Seated Dancer in Profile,” in which the poet calls on the art of Degas to reflect on a dancer gracefully depicted, though facing the horizon behind her. “To love her is to accept that she will never turn around,” the speaker reflects, which is not unlike her relationship with her mother. The speaker longs for her mother’s survival, yet she must accept that the mother’s decisions are her own.

In the second section, the speaker turns toward reflection and memory, which is full of her mother’s past and empty of the speaker’s own unknown future. As she comes to terms with separating from her mother, the dancer no longer dances with dignified poise, but “yearn[s] for the ballet master,” and for the life she once had that resembled a sense of refinement. Now, though, she recalls “seeing us together / in our white tutus— // like roses standing naked / on a coffin.” Here the themes of life and dance merge. With the loss of her mother, the dancer becomes unrecognizable to herself. It is in this section of poems that the speaker’s mother dies, “as was her plan,” and it is also where the speaker comes to terms with acceptance: for what she can control and that which she cannot. In the title poem “The Tulip-Flame,” the speaker confesses “It’s simpler to imagine something could / have intervened,” acknowledging her struggle to prevent the inevitable, while understanding how little control she had over her mother’s fate.

Themes of loss and control carry on in the “Fever” section of poems as the speaker turns her reflective tone toward a failed romantic relationship. Still wounded by the loss of her mother, the speaker has “grown / fond of silence, how it sits / beside me like a pet.” Yet even in her familiarity with silence, the speaker clings to what once blossomed yet now no longer exists: “Alone, which has grown to mean without you.” In this poem, the speaker weaves in and out of acceptance, recognizing what she has lost, but not removed from denial as she “imagine[s]: you’ve just left and will come / back for me soon.” A failed romance may feel like death, but unlike the experience of losing her mother, the speaker believes she has a chance to reconnect with her lover. This belief, though short-lived, is the speaker’s only way to exercise control. She cannot bring her mother back to life, but the poem suggests her relationship has potential to be revived.

In the final section, “Dusk,” the speaker settles in with a new life, having accepted her losses. In the poem “Evening News,” she moves beyond sheer acceptance into a realization that part of her mother lives on with her, even after death: “it crosses my mind / how gone you are, and stars, / if stars say anything, say Otherwise.” She may have physically lost her mother, but the memories stay alive within her and the speaker now allows her memories to live and breathe on their own. Like the sentiment from the opening poem, “Spring,” the speaker embraces how life continues in its own unpredictable way. From chaos and uncertainty, life is revived in due course.

Published 5/12/2015

About the Reviewer

Lori A. May writes across the genres and drinks copious amounts of coffee. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Brevity, and Midwestern Gothic. Her sixth book, The Write Crowd: Literary Citizenship & the Writing Life, was published by Bloomsbury in December 2014. She lives online at

www.loriamay.com.