Book Review

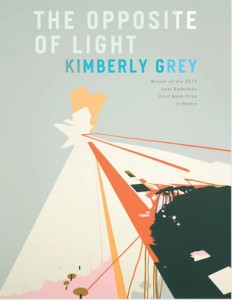

In her debut poetry collection, Kimberly Grey constructs grammatical worlds as a form of time travel. The Opposite of Light, winner of the 2015 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry, deploys grammar’s intricacies to explain the emotionally fraught complications that arise with distance, loss, and uncertain, untenable relationships. While sparse in number, these visually varied poems embody how textual and physical worlds collide: there are trials the speaker must face when navigating intimacy and in being able to express that intimacy within the realms of language and memory. In this collection, Grey mines vibrant grammatical traditions to illuminate memories, crafting them into little worlds of their own. This world-building begins with the sentence.

In her debut poetry collection, Kimberly Grey constructs grammatical worlds as a form of time travel. The Opposite of Light, winner of the 2015 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize in Poetry, deploys grammar’s intricacies to explain the emotionally fraught complications that arise with distance, loss, and uncertain, untenable relationships. While sparse in number, these visually varied poems embody how textual and physical worlds collide: there are trials the speaker must face when navigating intimacy and in being able to express that intimacy within the realms of language and memory. In this collection, Grey mines vibrant grammatical traditions to illuminate memories, crafting them into little worlds of their own. This world-building begins with the sentence.

Devoted to the sentence and its possibilities, Grey explores the broad category of the sentence through labeling memories as sentences. Interspersed throughout the collection, these “sentence” poems illustrate the sentence’s many reincarnations as well as how syntax and line generate momentum in language. The rolling conjunction “and” in “American Sentences” pushes the poem’s narrative forward, as the speaker tries to piece together a love story that takes place in the city: “Is this a love story for a man / or a country and what’s the difference / anyway?” The speaker continues this fatalistic train of thought, considering the relationship’s inevitable end: “it’s all provocative / and retrospective now, and before you / know it you are someone else’s baby.” Filling, rather than emptying, relationships, the speaker in “Hunger Sentences” calls back to the earlier poem, as the lovers have sex before eating. “If we weren’t starving for one thing, / we’d starve for another. We are American, / after all,” the speaker observes, fixating on carnal desire and bodily existence.

The sentence’s accoutrements follow suit in these syntactical explorations. The conditional “if” makes appearances throughout The Opposite of Light, beginning with “Conjugating,” where the lovers consume each other in every tense of their relationship. In attempts to make repairs, the speaker reminds the other, “That when I promised / you time, I promised nothing but the notion / of it.” The “if” that leads off the poem and ends as a question serves as the speaker’s inability to answer. And yet the speaker already knows the answer—that the pain will continue regardless of what actions are taken. A column poem, “Conditional Dreaming,” envisions a speaker who considers how “Your body is a place / (sometimes a thousand places) / depending on how it’s sold, bought.” In the tight, constrictive space of the poem and the dream within the poem, the body contains possibilities unavailable within the physical world, the short span of the relationship.

The body expands and shrinks—from nation to imagined space to physical, visceral flesh—in The Opposite of Light. Grey uses grammar and syntax to navigate and negotiate time in these poems, where moments in the past and present can be examined in minute detail, even from beyond the moment’s perspective. This visually textual manner of presenting memory through poetry demonstrates a reverberating power. “A Reconstruction of Memory” opens in the regretful conditional:

If only we weren’t a war, a history

I must keep. Then I’d work

my way through our ages, take the good

years and spill them

out on the floor in front of us.

Through the poem, the speaker can reorganize the sequence of events, viewing every aspect of the relationship through the assemblage of memories and objects that follow. This controlling process recaptures the past and forces it into the present. However, this act has a terrible consequence, as the final two lines show: “Grief is the machine / that lets us keep each other forever.” The poem, too, serves as a machine that cycles through that grief, giving syntactical order but not relief to an otherwise messy and unrepeatable sequence of events.

The Opposite of Light offers a momentary glimpse into the shards of a relationship that have been carefully pieced back together using poetry’s inner logic and grammar. While grammar and syntax may act as a form of time travel, they are unable to provide closure. Grey’s close attunement to the minutia of poems lends this brief collection weight; the more memory is reconfigured and reconstructed, the more there is to lose again.

About the Reviewer

Alyse Bensel’s poems have most recently appeared or are forthcoming in The Adroit Journal, Zone 3, Quarterly West, New South, Bone Bouquet, and elsewhere. She is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Not of Their Own Making (dancing girl press) and Shift (Plan B Press), and serves as the Book Reviews Editor at The Los Angeles Review. A PhD candidate in creative writing at the University of Kansas, she lives in Lawrence.