Book Review

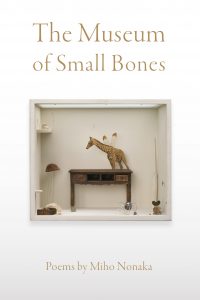

It seems ages since I walked through a museum. Of course, it’s only been a little more than two months since their doors were shuttered for the Covid-19 pandemic. And prior to moving to a city, more months would regularly pass between visits. My parents often took me to museums on vacation growing up, and it remains a given that we will visit at least one when they fly out to visit. Citadels of culture, art, and knowledge, museums are also fraught with a history of colonialism, looting, and the racist promotion of a singular trajectory of cultural progress toward Western aesthetics of the ideal. They are sites of violence. The father of birding himself, John James Audubon, killed thousands of birds in the name of preservation, in order to bring them to museums and Western society through paintings and taxidermized specimens. This underlying note of violence threatens to escape the poems Miho Nonaka writes to contain it in The Museum of Small Bones.

When learning to speak English, “The word harm never appeared in any of my textbooks,” Nonaka writes in the opening poem, “Rupture.” In the poem, the speaker is a child cooking marbles to release the “nebulous damage contained within clear little balls” as the radio relays news of the emperor’s impending death: “No longer a god, but a symbol emptying itself.” This tension between containment and the threat of rupture drives the collection onward, as does the tension underlying the meeting of two cultures, the endeavor of a bilingual poet from Tokyo writing poetry in English in both lineated and prose form, as in the second section, “Production of Silk.” The story is texture. Or rather, “Texture is story. Whose skin would brush against it, and for what occasion?”

The poems in Nonaka’s collection teeter between a desire to contain and be contained, between rupture and rapture, naming the nature of our harm as such and accepting the limits of our own small existence:

. . . It’s no accident

nightmares visit your town

in circular tents. Arms stretched out,

I will walk the tightrope,

never straying from the line

between reality and dream, beauty

and damage. No desire to ever

wake up on either side of the border.

We delight in the distractions of the circus, though we understand its wonders are illusions, our voyeurism and demand for entertainment perhaps culpable in the continued othering of those outside the sanctioned norm. And though we begin to see where the line between reality and dream have been laid, begin to see the structures that fix that line and by extension the barriers it creates, the us and the them, we choose to follow it. We neither look too closely at the dream nor the reality lest we wake alone on either side. We who are fortunate to be so able to choose, choose not to choose, and the show goes on. If not in rapture, nevertheless still alive in the rupture.

And what are museums if not structures in which both rapture and rupture are at once suspended and celebrated? Why do we frequent museums if not at once to escape our own singularity and also confront it? Museums simultaneously broaden our view of the greater world, of the diversity of peoples and achievements even as they reinforce a stereotyping sense of othering. Is there another way forward? Contemplating on her own position as tourist in another country, as one looking out and seeing other, Nonaka writes, “my senses became both numb and painfully acute the more I focused on the inconsequence of my being there.”

Do not, however, mistake The Museum of Small Bones for a monotonal lament of those very tensions that evoke our truest human condition. Despite palpable underlayers of violence, these are poems that remember there is also beauty, and that “The earliest Japanese poets attached power to longing.” And if the exercise of containment is fraught with rupture, so too such small works, as silkworms spinning silk from mulberry leaves, as the jewel box in which the poet keeps them at their work, as the marbles encasing their nebulous damage, “From day to day, far from the sublime, what saves me is not magical encounters or words of charisma, but small works I am equipped to do, tasks that require faithful use of my hands, shaping things for someone beyond my immediate reality.” And what we find contained in museums—and in poems—remind us equally of all the ways we are linked, that despite our separation, our daily isolation, “we are strong//enough to sing against the ringing of something/ever-splitting, something more than indifference[.]”

As fitting a museum, the poems in Nonaka’s collection are at times eclectic: in the long serial prose poem that comprises the second section, “Production of Silk,” we get a seemingly unconnected episode on a visit to the Spanish synagogue in Prague. But that, I believe, is the work of poetry, and the work most necessary to such times when our distance is felt most poignantly: to build connections. Or rather, to reveal them. The poems, like artifacts or displays in a museum, become launch points for considering an assemblage of observations in the context of an exhibit-in-poem on the production of silk. The silkworm, like those common household items exotified in the museum, is itself the thread of both daily life and our efforts to spin meaning from the accumulation of our days. And perhaps we gain insight into the role silk plays in Japanese culture, but as with any museum, more of our own desires are reflected back to us than any true knowledge of the other. In the museum, as in the poem, we project our own questioning and mysteries in an effort to connect to—what? To others? To ourselves? To arrive at some understanding of our own knowledge’s shortcoming? Or perhaps to recognize our desire to exist with purpose as does the silkworm. “There are more voices you didn’t know you have,” the poet reminds us.

Perhaps what Nonaka’s poems achieve most notably is to reflect our own imperative to sing the song that is only ours, that is incomplete but sincerely ours and our responsibility to sing.

. . . I dreamed of a power

to make small, imperceptible things

perceptible, like the pattern of bones of a bat

in flight. The power to stave off our despair.

In these poems we find not only that which we can contain, but that which may contain us. Perhaps we turn to poems for the same reason we continue to frequent museums and collect shells and rocks and other small ordinary treasures: to find the self, yes, but to find the point from which we depart the self, become separate from and more than the singular self.

About the Reviewer

Abigail Chabitnoy is the author of How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan, 2019), shortlisted in the international category of the 2020 Griffin Prize for Poetry and a finalist for the Colorado Book Awards. She was a 2016 Peripheral Poets fellow and her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Boston Review, Tin House, Gulf Coast, LitHub, and Red Ink, among others. She is a Koniag descendant and member of the Tangirnaq Native Village in Kodiak. Visit her website at salmonfisherpoet.com for more information.