Book Review

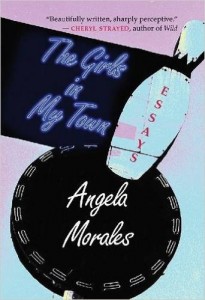

The winner of the 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, Angela Morales’s debut collection of essays explores her coming of age. Morales examines the impact of the important women in her life, as well as some unlikely heroes. In her introduction, Morales refers to her autobiographical essays as her “oddly shaped children” who “all line up and stand . . . side by side . . . [as] beloved orphans . . . in one family portrait.” With humor and compassion, Morales vividly captures the quirky imagery of growing up in 1970s Los Angeles. Thus, while Morales’s individual essays offer richly crafted scenes depicting her moments upon adulthood’s threshold, the collection as a whole provides an intimate, warm-hearted meditation on what it means to live and learn as a compassionate daughter, mother, and teacher in an unkind world.

The winner of the 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, Angela Morales’s debut collection of essays explores her coming of age. Morales examines the impact of the important women in her life, as well as some unlikely heroes. In her introduction, Morales refers to her autobiographical essays as her “oddly shaped children” who “all line up and stand . . . side by side . . . [as] beloved orphans . . . in one family portrait.” With humor and compassion, Morales vividly captures the quirky imagery of growing up in 1970s Los Angeles. Thus, while Morales’s individual essays offer richly crafted scenes depicting her moments upon adulthood’s threshold, the collection as a whole provides an intimate, warm-hearted meditation on what it means to live and learn as a compassionate daughter, mother, and teacher in an unkind world.

Morales situates her story within the hazy, working-class outskirts of Los Angeles and does not miss any opportunities to reflect on her past misperceptions. In the essay “One Small Step,” Morales recollects her eleven-year-old perspective on the nation’s shifting social context amid the women’s liberation movement: “families seemed to be falling apart—my own included—and we couldn’t decide if that was good or bad.” Morales, inspired by Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, challenges her school’s status quo of allowing only boys the privilege of working in the highly coveted position of cafeteria dishwasher. So she and her friend, Lara, take their battle to the student council, and win. But the sweetness of this feminist victory soon sours when at recess the girls are encircled by a group of jealous, rock-hurling boys. Morales continues to smartly sprinkle her recollection with irony: “And these . . . were good boys who came from good families . . . What did they have to be angry about?” Even though Morales ends the essay with the girls escaping from the extremely gendered charade of a sixth grade school dance, readers appreciate Morales’s ironic treatment of this brief moment, which defined Morales’s sixth-grade concept of feminist progress.

Morales juxtaposes whimsy with the disappointments of her childhood, which allows her to create a high-spirited collage of everything from her grandmother’s racy courtship with her grandfather, to a series of eulogies for all the dogs she has ever owned or loved. Notably, in “The Burrito: A Short History,” Morales embraces her Mexican-American heritage, as she traces the etymology of the word burrito to images of her mother “eating her lunch in the school bathroom, always ashamed of food that looked and smelled so ethnic.” This essay is short, but Morales goes on to powerfully reclaim the burrito as not only highly portable, versatile, and currently en vogue, but also as an act of faith, because “what’s inside is naturally concealed by the cylindrical structure…a mystery.” In this way, readers get a sense of Morales’s value in her Mexican-American culture, which is also punctuated with her unique honesty and humor.

Morales’s careful reflection on her past perceptions does not end with her examination of her childhood, but reaches into her current work as a writing professor. In the most heart-wrenching essay of the collection, “Bloodyfeathers, RIP,” Morales shares the story of the menacing ex-con who joined her remedial writing class at central California’s Merced Community College. Bloodyfeathers is one-of-a-kind who, defending his unconventional name, introduces himself, “That’s what it says on my birth certificate . . . My dad wanted me to have a warrior’s name so I could beat the shit out of people.” Morales illustrates her new student as “lumber[ing] to the front of the room,” but even more telling is her attention to Bloodyfeathers’s impact on her other students: “a sudden gravitational compression occurred, or the air pressure changed somehow, as [they] flattened themselves into their desks.” Despite his alarming demeanor; homemade tattoos; and “smallish nubs of teeth that had either stopped growing when he was six years old or had been filed down on purpose,” Morales describes, echoing the old teaching adage, how Bloodyfeathers teaches her more than she does him. Morales realizes that her job “was not to judge but teach—to give this man a small door that he could walk through.” Unfortunately, as alluded to by the essay’s title, Bloodyfeathers’s end comes too quickly, but the real focus of this essay is on Morales’s examination of her own assumptions. Through her reflections, she teaches the reader to find meaning in examining one’s own past judgments.

Morales closes her collection with the same careful observations with which she opened. In the titular essay, “The Girls in My Town,” Morales braids the anxiety she felt as a new mother with her contemplations on Merced’s high population of teenage mothers. On an early morning walk, Morales pushes her daughter in the stroller past “the Bad-Girl School,” a continuation high school, where the young new mothers walk, like prisoners, along the track fence in matching gray. But despite this grim reality, Morales closes with the hospital scene after giving birth to her daughter. She shares the room with another new mother who is only fourteen years old. Morales describes the common ground they find, despite their seventeen-year age gap, and Morales’s automatic assumption that the teen’s daughter will face many of the same challenges her mother has. In the essay’s final lines, Morales shifts from this judgment and ruminates on hope: “As for our daughters, the fortune-teller might peer into her crystal ball or examine our girls’ palms and see a whole web of alternate realities. ‘Anything can happen,’ she might say. For all of us, the road is wide open.”

As a whole, Morales’s collection offers a tender and affectionate perspective on the struggles she and others have faced growing up in America. Morales’s honesty and well-placed humor encourage readers in their own lives to continue to find humanity in unexpected places.

About the Reviewer

Jamie Utphall is a graduate student in English at University of Wisconsin Eau Claire interested in nineteenth century African American women’s writing. In her spare time, Jamie also enjoys writing short stories and short memoirs.