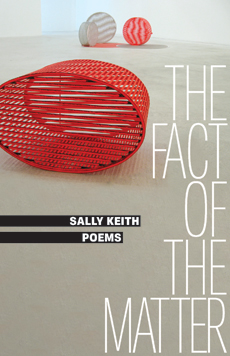

Book Review

There is a set of instructions one should follow before reading Sally Keith’s The Fact of the Matter. First, make a knot with your hands by wrapping your fingers around one another and gripping them tightly. You must add extra fingers to your hands so the knot, further complicated, looks impossibly rational to anyone watching you follow these instructions. You must think of your fingers, all twelve of them, all eighteen of them, as your wares. Ply your wares in such a way that you manufacture a bodily logic.

There is a set of instructions one should follow before reading Sally Keith’s The Fact of the Matter. First, make a knot with your hands by wrapping your fingers around one another and gripping them tightly. You must add extra fingers to your hands so the knot, further complicated, looks impossibly rational to anyone watching you follow these instructions. You must think of your fingers, all twelve of them, all eighteen of them, as your wares. Ply your wares in such a way that you manufacture a bodily logic.

Such a knot is assuredly Sally Keith’s form, especially in her third book, The Fact of the Matter. Consider the poem “Knot.” Did you know the spine is made of knots? Twenty-four of them. Did you know the spine is stained by blood? Bathed in it. Did you know the rhinoceros printed by Dürer looks like an armored contraption? Like Dürer’s rhinoceros, which partially resembles Keith’s description of the spinal column as a “series of knots under skin,” a poem should hold what is unspeakable inside it. “Knot” shows, as do many poems in this collection, that Keith is the cantor of the implicit. Take this selection from “Knot,” which follows an allusion to the scene in Book VII of The Iliad where Ajax and Hector step into battle. Keith considers what may be going through their minds:

Can you hear a sound in the back of your head urging against this?

Go home, go home.

Blood stains all systems in the body an equal red, explains Leonardo:

“You can have no knowledge of one without confusing and destroying the other.”

Nearby Dürer paints on linen.

Dürer cuts a block of wood to print The Sixth Knot on Italian paper.

Keith works from the fear of intention to the anatomy of intention to the philosophical underpinnings of intention to intention’s art. All thoughts, knotted together, are mutually relevant and mutually referencing, for if “the spine is the series where all action begins” (a statement made earlier in the poem), then all action must carry with it the complicated structure of the spinal column. Imagine Dürer’s print of a rhinoceros actively lumbering through the streets of Lisbon. Do you see the image of intention here? Is it encumbered by armored plates?

Intention and the dissected anatomy of intention have always been at the center of Keith’s work. Her first book, Design, touches on loss, but not with the presumption that her reader needs to participate empathetically with the speaker’s grief. Rather, Design is more the design of grief inside the body. As Keith writes in “Migration,” a poem from Design, “That ghost in me. That blown net, / a gate at the base of the mouth, unsheathing / words, turning them to speech.” The tangle of migrating birds is a model of strife that the speaker absorbs into her body, and that emotion, along with its particular construction, creates its own intentionality for the speaker.

The Fact of the Matter is lost in intention, but “lost” in the constructive sense of the word. In the book’s central poem, “What Is Nothing but a Picture,” the intention of intention is intentionally obscured. While that might sound like a bit of tricky wordplay, how else could one describe a speaker who is painting a mural of a battle that may or may not have been decided? In this painting, the victor is hardly the most important feature. Instead, the act of painting is most prominent. The painter’s life while he’s painting is a life that is continually altering, perhaps because the painter actually lives inside the mural. From Part XI:

The battle scene should be cleared

of bodies blocking the field. Help will

have to be hired in taking the stump

down to the ground. What do you call

the problem of losing words on the way

to your throat? They’ll have to hire men

to grind the stump, wait for the roots

to disintegrate, malnourished then, for

the roots to turn into earth, for the loam

to let the roots back in. Where is the quill;

the lantern, the desk of oak?

Is the painter here asking that the painting be erased of bodies so the field can be painted first? Does the stump exist in actuality, or is it a stump that appears in the painting and requires an imagined crew of hired men to grind it down? These potential confusions of reality versus canvas, of work crew versus army, and of circumstantial life versus mural narrative are layered throughout the poem.

I would contrast this technique in “What Is Nothing but a Picture” with that in “Rooms Where We Are,” a poem from Keith’s second book, Dwelling Song. In “Rooms,” Keith relies on a clipped, self-reflexive fragment. The gesture is so brief, however, that I am uncertain how much empathy I am supposed to give the reading and how much emotional weight the fragment is meant to evoke. What is at stake emotionally as I move from section to section of “Rooms”? How does this seemingly empty space impact the speaker, and how, then, is the reader affected?

But light is not

wind. I sent it.

And the sky went

gray lost texture. I

tried to still it.

Then smoke. Then cars.

I’m left wanting, which, from the implied emotional weight in the poem, is not what I think the poem intends. In many sections of “Rooms,” I can sense the emotional consequence (“Let me live— / where cove ice is / coming fast), and I am aware that it lies just outside my reach. Why does the poem require me to travel so far to meet its point of consequence? Am I not being generous enough as a reader? Many poems in Dwelling Song may make me cognizant of a crisis, but I don’t feel involved in it, which is what I’d prefer in this case.

There is no such distance in The Fact of the Matter. Keith unfurls her fragments, but these fragments are the product of a relaxed voice. They gather beneath a series of impressions and intentions. They lay out a lush paradox. Keith sets many poems in a marshland, or at least references one. A marshland seems like an obvious formal description for these poems because it doesn’t resolve—it moves in on itself and away from itself. It shows the nature of Keith’s careful stitching of concepts. The most difficult task of describing The Fact of the Matter is doing justice to this stitching. Keith’s multiple narratives speak individually and collectively of a single idea, but the stitching is loose. This allows all the more space for Keith’s delightful knots to draw themselves into even more complicated forms.

About the Reviewer

Kent Shaw's first book, Calenture, was published by University of Tampa Press. His poems have since appeared in the Believer, Ploughshares, Boston Review, TriQuarterly, and elsewhere. Other book reviews can be found at the Rumpus. He is currently an assistant professor at West Virginia State University.