Book Review

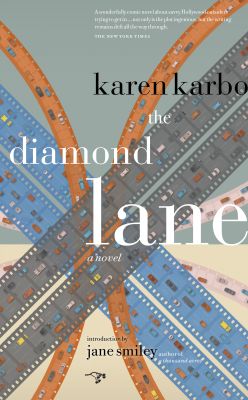

Karen Karbo’s The Diamond Lane offers a unique and humorous perspective on the materialistic values of Hollywood. An award-winning author, Karbo has published fourteen books: novels, memoirs, and nonfiction, including her best-selling “Kick Ass Women” series, a nonfiction series in which Karbo commentates on the lives of powerful women of the twentieth century—Julia Child and Audrey Hepburn, for example—and on the life lessons one can take from their stories. The Diamond Lane, first published in 1991, was Karbo’s second novel and was selected at that time as a Notable Book by the New York Times. The novel was reprinted this year as part of Hawthorne Books’ Rediscovery Series, an initiative to republish exceptional works by living authors. In the author’s foreword to this reprint, Karbo describes, Karbo describes The Diamond Lane as “an emotional autobiography,” using autobiographical elements to tap into “true, powerful, and usually conflicting emotions . . . to animate the characters and power the action.”

Karen Karbo’s The Diamond Lane offers a unique and humorous perspective on the materialistic values of Hollywood. An award-winning author, Karbo has published fourteen books: novels, memoirs, and nonfiction, including her best-selling “Kick Ass Women” series, a nonfiction series in which Karbo commentates on the lives of powerful women of the twentieth century—Julia Child and Audrey Hepburn, for example—and on the life lessons one can take from their stories. The Diamond Lane, first published in 1991, was Karbo’s second novel and was selected at that time as a Notable Book by the New York Times. The novel was reprinted this year as part of Hawthorne Books’ Rediscovery Series, an initiative to republish exceptional works by living authors. In the author’s foreword to this reprint, Karbo describes, Karbo describes The Diamond Lane as “an emotional autobiography,” using autobiographical elements to tap into “true, powerful, and usually conflicting emotions . . . to animate the characters and power the action.”

The Diamond Lane begins with Mimi FitzHenry, a receptionist for a talent agency and aspiring actress/screenwriter, telephoning her sister Mouse, a documentary filmmaker in Africa. Mimi asks Mouse to return home because their mother, Shirl, has had a tragic, if comic, accident with a falling ceiling fan. The novel follows Mimi and Mouse and their family and friends in the months after Mouse’s return home. A begrudging acceptance of an engagement, a wedding, a documentary, a worsening screenplay, and the convoluted intricacies of past and present relationships are all elements of the work.

Karbo’s clever title captures the many levels of her humorous, insightful commentary on Hollywood. The “diamond lane” refers to a car lane on the freeways of Los Angeles, used by cars with more than two passengers and designated as the fast lane through the traffic-filled highways of the city. The title suggests that the many who aspire to make it in Hollywood are looking to take “the diamond lane,” a shortcut to success, and that in many instances, as the characters of the novel discover, it takes speeding down the highway with others to realize who you are and what you really want.

Moreover, the title conjures wedding imagery—modern marriage being another theme of the book. The Diamond Lane juxtaposes the tendency of many young American women to see a white dress and diamond ring as a kind of finish line, the ultimate accomplishment of womanhood, with the same women’s common complaint that marriage steals away their hard-won independence. As Mouse’s wedding planner, Nita, says, “Used to be, everyone wanted to be free. Now everyone wants to be trapped. But at least they can do it in style, right?” Even back in 1991, Mouse agrees to have the entire process of her wedding filmed for a documentary that Ivan, Mimi’s ex-husband and Mouse’s first love, is filming. This novel’s relevancy may lie in the fact that Karbo seems to have predicted the trend toward making weddings and marriage into fodder for absurd television shows (Say Yes to the Dress, Bridezillas, Whose Wedding Is It Anyway, et al). Moreover, her depiction of Mouse’s moral degradation as she becomes more interested in the materialistic aspects of her wedding than the life commitment ones foretells our twenty-first century reality show brides.

Karbo’s satirical portrayal of the materialism of Hollywood is as apt today as it was more than twenty years ago. She gives us Ivan, the documentary filmmaker selling his organs and using sex with wealthy women to fund his documentaries; a preposterous “Save the Elephants” party hosted by a wealthy family that not only brings in a “gang of Africans in full tribal regalia” to speak on the growing need to save the elephants, but the party also includes an actual elephant in a cage on the beach. In addition, there’s Tony, Mouse’s fiancé, who when first seeing Los Angeles, observes that “in each minimall, the same shops, [were] all geared in some way to the upkeep of feminine beauty. … There seemed to be a preponderance of shops that recycled the same four words: Happy Nails, Friendly Nails, Friendly Rosy Nails, Rosy Happy Nails.” And there’s V. J. Parchman, the quirky man who works for Columbia Pictures and assists Tony with selling his screenplay. Karbo explains how Hollywood has created a senseless want of material things through V.J.’s absurdly blunt statement:

This is what I learned … from Hollywood…the rich man, his worry goes for useless, stupid things. Frequent-flyer programs are not a thing. It makes your soul feel like a used condom tossed out the car window … but what am I supposed to do … lose all those miles?

The Diamond Lane isn’t some lackluster analysis or vehement, dry criticism of materialism. Rather, the reader laughs along with Karbo at the consumerism to which we have all fallen victim to at one time or another, while still being able to consider how it affects the many characters in the novel and its role within our own lives.

Although the novel has many strengths, both the overwhelming cast of characters (over fifteen recurring characters) and the way in which Karbo uses multiple points of view become tiresome at times. With so many minor characters, they become difficult to remember. This may have been a strategy to depict the sheer abundance of individuals trying to succeed in Hollywood, and their failure to stand out in the crowd. Similarly, Karbo’s use of multiple close third-person points of view can become confusing. She delves into the thoughts of not only Mouse and Mimi, but also Tony, Mouse’s fiancé, as well as pulling back to a more omniscient viewpoint, leaving us scrambling to figure out when the narrator is switching to a different character’s point of view, and wondering why we are being held at arm’s length from these characters from time to time.

Similarly, Karbo’s creation of “the Pink Fiend,” a made-up conscience with traditional feminine characteristics that speaks in Mouse’s mind and is mostly depicted in italics, seems at times unnecessary and jarring. Mouse describes the Pink Fiend as either “her girlhood self or just a brutish enforcer of feminine values that lurked in the gene pool … passed on, quite visibly, from mother to daughter.” And though the Pink Fiend successfully illustrates the self-doubt that many women feel, its role as a character (as opposed to a voiceless idea or tool) feels unnecessary. Frequently the Fiend’s comments are redundant, as the reader had already drawn these same conclusions from Mouse’s keen internal insights.

These small criticisms aside, The Diamond Lane is a novel worth reading not only for its satirical sendup of Hollywood and its materialism, but also for its continuing relevance to the American way of life more than two decades after its first publication. Karbo speaks to all of us who have struggled to achieve our dreams, been fraught with the need for self-discovery, navigated intricate family relationships, and so often felt besieged by the expectations of society, especially in marriage. The Diamond Lane aptly captures the struggle to become an adult—especially for those who have daydreamed about forging a life in the glamor of the entertainment industry—in a way that makes us laugh out loud in the break room of our tedious day jobs, in the library of our film schools, or in one of our many hipster coffee shops.

About the Reviewer

Alex Temblador is a fiction and nonfiction writer currently based out of Los Angeles, California. This is her second book review in Colorado Review. She’s had fiction published in Cigale Literary Magazine and Scissortale Review and has recently had articles published by a variety of outlets such as the Huffington Post and Thenextfamily.com.