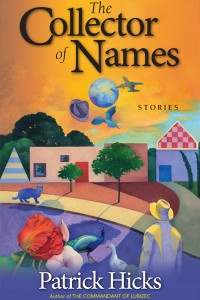

Book Review

The Collector of Names by Patrick Hicks is an uncomfortable book. It deals in disquieting moments and raw emotions. Readers will want to put the book down to get away from the difficulties of human existence that are brought too vividly to life by Hicks’s stories. Having put it down, however, readers are equally likely to feel the pull of the tales calling them back. The immediacy and urgency of the depiction of crisis moments make these stories magnetic.

The Collector of Names by Patrick Hicks is an uncomfortable book. It deals in disquieting moments and raw emotions. Readers will want to put the book down to get away from the difficulties of human existence that are brought too vividly to life by Hicks’s stories. Having put it down, however, readers are equally likely to feel the pull of the tales calling them back. The immediacy and urgency of the depiction of crisis moments make these stories magnetic.

Most of the stories in The Collector of Names portray elements of modern existence in the midwestern United States, with characters who are ordinary enough that it seems they could know one another around town. Some of the stories explore a familiar struggle: an odd person out trying to navigate a disinterested world. In the title story, for example, the narrator defines his life in terms of a written catalog of people he has met during his life. In “Picasso and the Tornado,” a chubby girl finds the courage to become an artist after living through a tornado. In “The Chemical Equation of Loss,” a woman seeks consolation for the death of her father and the loss of her mother’s consciousness.

Part of the pleasure of these stories lies in the familiarity of their predicaments and the plausibility of their resolutions. However, Hicks is also not afraid to venture into the realms of the fantastic. “The Lazarus Bomb” tells the story of a World War II bomber whose bombs restore his target instead of destroying them, and “The Missing” is about a trio of neighbors who find that a long-dead figure from each of their lives has returned to them. These stories are handled just as deftly and their resolutions feel just as inevitable as in the less fantastical ones.

What is not immediately obvious about this collection is that all of the stories share a common strand: confronting loss in its many guises. This commonality creates a reverberating pleasure while reading. Each story builds on and replays similar notes, like different instruments playing together in an orchestra.

In some of the stories, the loss at issue is the death of a loved one, as in “Invisible World,” in which a woman unravels in the face of the death of her mother and the simultaneous departure of her spouse. Or in “Cabin #5,” in which a young wife is unable to connect with her military spouse, who suffers from PTSD, which ultimately kills him. Each of these is a survival tale for the living left behind. Others portray loss through death on a societal level, as in “57 Gatwick,” about a local coroner in the aftermath of a plane crash. “Living with the Dead,” the story of the strange, but appropriate, first date between the son of an undertaker and the daughter of a breast cancer patient. Whatever the context, Hicks forces his reader to face death squarely. As the protagonist in “Living with the Dead” recalls: “‘Maybe,’ my father said, ‘maybe it’s not healthy to keep death from a nation? It makes us forget how precious each day is….’”

But death is not the only way the book addresses loss. There are also stories that confront loss in a more abstract way, as in the loss of expectations or narratives of memory. Take “Wood Shop,” a first-person account of a journalist researching a story he remembers from his youth about the day a classmate used the school’s drill press on his own leg. It’s an apparent tragedy until we learn that the leg in question was an often-replaced wooden fake and that this prosthetic was something of a trophy, envied by the other kids. The protagonist adores this story. It is part of his personal legend. But when he conducts a formal interview, he discovers that the shop teacher, who should have been a direct witness, has no memory of it. Ultimately the protagonist decides not to seek further corroboration because the tale is too important to his sense of self. While this is not loss or ostracism in any traditional sense, the story still touches on the loss we feel when a memory is stolen from us.

“Burn Unit,” a story of the aftermath of a fire, falls into the category of loss of expectations. An aunt quietly comes to terms with the fact that her pleasant life must change so that she can parent her injured niece. This story is perhaps the sneakiest in its exploration of the theme of loss because the story seems, on the surface, to be about much more attention-grabbing things (fire! pain! abandonment!), but the protagonist’s thoughts—as a mere spectator to the seeming action—form the real narrative. Here, as elsewhere, Hicks hits his reader with emotionally powerful descriptions: “This house fire had been branded onto her skin. The past was tattooed deep into her flesh. Decades of gawking strangers waited up ahead.” And yet the reader retains affinity for the characters and a certain optimism that everything will be okay, despite it all.

More than simply cataloging or describing these confrontations with death or loss, this collection offers readers hope about how they might face character-defining moments and come out undaunted. Hicks does so without pulling any punches to soften readers’ discomfort.

For example, “Leaving the Hospice” is a brutal story of an adult son’s decision to place his ailing father in end-of-life hospice care, and it leaves the reader feeling like a wrung towel. The poetry of the story particularly comes from its refusal to sugar-coat any portion of the son’s experience: “His unconscious father, who was once a mailman, a choir singer, and a little league coach, breathed on in irregular gasps, he was a sucking black hole with shuttered eyes.”

It is a strong reader who won’t find him- or herself tearing up and then smiling through those tears. Hicks once again demonstrates how we may confront death, loss, and non-being, yet still come through it without having averted our gaze. There are moments in the collection that feel somewhat over-orchestrated, but these minor missteps are small prices to pay for tales that are, overall, so compelling and inspiring.

About the Reviewer

Amanda Moger Rettig is a writer living outside of Boston with her husband and three children.