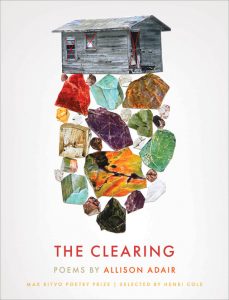

Book Review

The poems in Allison Adair’s award-winning collection The Clearing—electric, brilliant with loss and searching—gain strength and confidence as the collection progresses. The culminating “Bear Fight in Rockaway” remarks, “We’ve stopped worrying so much / about worrying” until two bears appear at the mailbox and tangle; their combat, the way “the bears’ bodies linger before they strike,” reminds the narrator that great trauma is often a heartbeat away: “we remember something of that from before / all the fences, the stairs and the cars, from a similar injury or kiss.” Many of the poems embrace a similar ethic in their theme: the world teems with beauties and wonder but also terrors we can only partially contain or conceal. As the poem “Whale Fall” signals, “Anyone who finds the sea placid / hasn’t been paying attention.” Adair’s poems bubble with tragedies that seem less unique than part of the common hum of human experience.

Perhaps we mythologize to handle our burdens, and Adair’s poems often create and embrace myths. The collection’s opening offer, “The Clearing,” suggests we may need new mythologies, or at least revised, to endure new terrors: “What if this time instead of crumbs the girl drops / teeth, her own.” Later, in the astonishing “Memento Mori: Bell Jar with Suspended Child,” lines simultaneously create a new myth (a unique lost child) while alluding to Sylvia Plath and a range of classical stories from Leda to Ariadne: “If he could, he would drink this river, / find the child at the bottom. Strangle the swan / and wrap our hard love in its wings.” Each poem embraces and contributes to a new mythology.

Some of the early poems feel jaunty and self-consciously stylistic, replete with fragments and brutal rhythms that, in part, feel like the music of their themes: “Fork-colored fan blades / warp stuck air into hymn” (“Memento Mori”) or:

The world’s getting bigger—truth is hard

To see. Try shaking a firefly until he vomits

Daylight. (Here’s wisdom they don’t print.)

The neon gel smeared across your hand can light

The way. Go ahead. Reach out for something dark. (“As for the Glossy Green Tractor You Were”)

The poems express the fuse-like warning of time: how what we get is not what we expect, that we may feel or see consequences only vaguely in the turmoil of a moment, and that history is always beneath us either in memory or literally. In “Debt,” the narrator says, “There’s a message / in his code: you’re afraid / of the wrong catastrophe.” In “Herr’s Ridge, 1983: A Reenactment,” one of several poems that brush up against Civil War battlefields, Adair suggests another way our actions intersect with time: while we are looking for the past (to understand, to accept, to move past), we miss what is alive, and while we are worried about past tragedies, new horrors surround us:

Their metal

Detectors warp and whine into the fields’ uncivil

Core. They live for war. But won’t trace the rabbit’s

Rapid pulse, bottom of the litter, drowning in the nest.

Subterranean images dominate Adair’s poems from old battlefields where collectors with metal detectors strive to uncover artifacts of the past to fields of snow that obliterate what was once vibrantly alive:

A black walnut’s roots

pierce the buried limbs of our grandfather’s fallen

spruce grove. The caterpillar inches along, lost

in its sad accordion hymn. (“Gettysburg”)

Emphasizing the same impulse, the poems embrace images of enclosure from caves and the bats who hide in them to jars of fruit arranged in cellars. Many of these images deepen the central metaphor of the pregnant belly and the life (and death) hidden within, but they also accentuate Adair’s insistence on the obscured world, the meaning that exists just beyond our seeing. If only we could locate the bullet fired from the Union gun or more clearly delineate what creature belongs to the eyes glimmering in the darkness, we could bring more light to the mysteries that are truly important to us: why did my baby have to die and what is the meaning of that small almost life? “I was a yellow stamen, then / a wheelbarrow full of empty sacks instead / of the ground you needed,” she writes in “Angelus.”

Adair deploys rich figurative language and enjoys a healthy conceit, often pulled through an entire poem. Experiencing a medical exam after a miscarriage is like, the conceit goes in “Ways to Describe A Death Inside Your Own Living Body,” looking for bats in a cave: first “I thought I knew the sound of darkness, the slow leather collapse of a bat’s wing” and then “for the bats under your ribs” and finally “the last headlamp can // finally click off and head // back into the night.” In later poems, we have conceits involving spiders, whales, rugs, and snails among others.

Our past dazzles, and the cost of dazzling is a present moment made spectacular but also poisoned. Experiences, memories from the past taint the current even as the sentimental joy enriches. We can’t seem to have one emotion without the other. But perhaps we need new myths to remind us of the glories, as in “RD 8 Box 16A (Rural Route)” when the speaker asks, “What ache is this” and then “So much gold, everywhere, gold.”

Despite being caught in the eddies of loss, returning in memory and emotion to past personal or collective horrors like domestic abuse, a bloody battleground’s dead, or a lost pregnancy, we can move forward. Adair’s imagery reminds us we aren’t always stuck:

We remember how to begin

again, day after day, letting others moor

Or latch as the ticking clock requires. For us, life

Drags on for two hundred years. Half-breathing,

Half-wake, floating or swimming.

The final poems are less mystical and more interested in finding rather than eluding (or giving in to the obfuscation of) meaning. A sudden impulse to narrative emerges, a kind of semantic order to help quell the chaos. In “At the Park One Day, My Six-Year-Old Asks Me if Mermaids are Real,” the narrator asks, “Can you blame me for saying yes?” The myths are true, both the ones the shield us from horror (Leda did not consent to the Swan’s embrace) and those that generate felicitous wonder and awe: “The park sprinklers spin, shoot / a fizzy mist, opal droplets glinting like fish scales.” As we read, we are on a journey into the woods with strangers, and The Clearing’s poems capture the beauty and terror of sudden, new site-lines.

About the Reviewer

Kyle Torke is a teacher of writing and reading, and he has published in every major genre. His most recent books include Sunshine Falls, a collection of nonfiction essays, and Clementine the Rescue Dog children's books.