Book Review

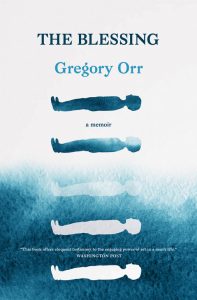

In the recently re-released memoir The Blessing, the poet Gregory Orr starts with two big questions. The first—“Do I dare say my brother’s death was a blessing?”—is the opening line of this slender, harrowing narrative of Orr’s dangerous, lonely, and redemptive childhood. The question refers to the death of his brother Peter, who Orr shot and killed in a hunting accident when he was just twelve years old. The second question—“Why was I spared?”—not only reflects on Orr’s survival from this unimaginable family tragedy, but eludes to his near-death many years later when, as an activist during the Civil Rights Movement, he is illegally detained and terrorized in the same Alabama hamlet where two other activists had been murdered. “It is a question that has moved like an underground river below my whole life since that day,” writes Orr, “moved there with the steady, insistent rhythm of a heartbeat,” and the author concedes from the start any possibility of reaching tidy conclusions out of the dark chaos of his early life. “I’m not sure there is any answer to my question . . . but I believe the answer to my question emerges from this odd word itself, this ‘blessing’ that conceals within its history such terrible words as ‘wound’ and ‘blood.’”

The wounds and blood are both literal and figurative. On the day of that terrible hunting accident, Orr learns his fate parallels that of his father’s. When his mother attempts and fails to comfort him, she reveals a family secret: his father accidentally shot and killed his best friend when he was nearly the same age as young Gregory. Orr’s mind fills with questions that will never be answered, at least not by his parents. Instead, it is in adulthood that Orr learns the details of the event, and is able to piece together it and other family tragedies—the accidental death of his parents’ first child; the slow unraveling of his parents’ marriage and untimely death of his mother; his father’s drug abuse, pathological recklessness, and philandering—to better make meaning of the trajectory of his own life.

Orr’s narrative is a page-turner and it’s easy to emphasize the sheer volume of tragic events that riddled his childhood, potentially overlooking the stark and moving prose in which he recalls his past. The most profound passages are contained in the space of non-events, when Orr runs wild through the rural landscape of upstate New York, catching turtles and fish, digging up bottles for his mother, riding horses and recalling “the sensation of peeling back the strata of hickory leaves—the top layers light brown and dry and lifting off in large patches like bandages, then each successive deeper layer darker and more compressed, the leaves now fragmented and finally wet and cold and traced through with white and yellow threads of mold.” It’s not difficult to see the metaphor here, not only of a family’s damaging history, but of the layering effects of poetry. It is poetry, after all, that saves Orr. Through art Orr finds his meanings and is able, in the end, to say yes to life.

Though full of artistry, Orr’s book is restrained, adhering dutifully to the facts of his childhood and early adulthood, moving swiftly, skipping overelaboration and speculation. While Orr says he is saved by teachers and poetry, his explanations hold readers at arm’s length. He reads “Wordsworth with pleasure because he seemed in touch with the actual, physical delights of nature,” and feels kinship with Keats because the poet has “no difficulty at all identifying with his desire to transcend bodily suffering through the ecstatic release imagination offered.” The book starts with two big questions, and concludes with many more that remain unanswered. In the midst of a near-suicide, what pulls Orr back to living? Why did his mother require the botched D and C that ultimately killed her? There are countless moments like these, ones in which the author demurs, reminding readers he was too young to know, or that his parents never spoke of it, or that he could no longer recall.

But books serve an infinite number of purposes, and it’s easier for me to forgive these absences when I consider the value of reading The Blessing during this moment in our nation’s history. The disturbingly violent and inhumane details of Orr’s experiences as a civil rights activist in the sixties underscore the sacrifices people were and still are willing—sometimes with their lives—to make. Now, as police shoot rubber bullets and use tear gas against the thousands of Black Lives Matter activists, as local law enforcement come up with false charges against protestors to restore “law and order,” and as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color continue to be persecuted by a society hell-bent on destroying them, some readers might understand this part of Orr’s story as a sad reminder of how little we’ve evolved as a nation. But as the writer reminds us “‘end’ is also purpose, your essential intention in life.” Despite his dark beginnings, Orr did not succumb to the terror of it; he was lucky and did not die. Instead, he writes, “my beginning of trauma and violence led me on to a lifetime of creation rather than destruction.” What might our country look like in ten, fifteen, twenty years, if we all were so bold as to envision our present moment in such terms?

About the Reviewer

Lenore Myka is the author of King of the Gypsies: Stories (BkMk Press). A recipient of a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, her writing has appeared in Poets & Writers, New England Review, Iowa Review, Massachusetts Review, and Quartz, among others.