Book Review

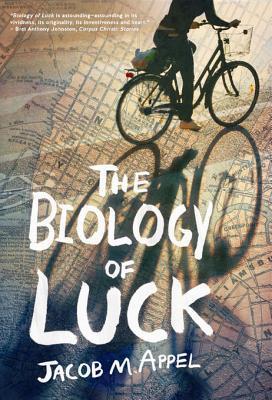

Jacob Appel’s second novel, The Biology of Luck, follows a New York City tour guide and lovestruck novelist, Larry Bloom, as he leads a flock of Dutch tourists around Manhattan on the day of his much-anticipated date with Starshine Hart, the girl of his dreams. Larry’s so consumed by his love for Starshine that he spends two years writing a novel (titled The Biology of Luck), which imagines her adventures on the day of their all-important dinner meeting where Larry plans to profess his love and find out once and for all if it will be returned. Also at stake is the potential publication of Larry’s novel—he’s received a letter from a literary agency, and decides to wait until after his date with Starshine to learn its contents—making Appel’s novel one about the tension between seemingly “inevitable” failure and “the remotest of hopes” for happiness in love, success in enterprise, and immortality in art.

Jacob Appel’s second novel, The Biology of Luck, follows a New York City tour guide and lovestruck novelist, Larry Bloom, as he leads a flock of Dutch tourists around Manhattan on the day of his much-anticipated date with Starshine Hart, the girl of his dreams. Larry’s so consumed by his love for Starshine that he spends two years writing a novel (titled The Biology of Luck), which imagines her adventures on the day of their all-important dinner meeting where Larry plans to profess his love and find out once and for all if it will be returned. Also at stake is the potential publication of Larry’s novel—he’s received a letter from a literary agency, and decides to wait until after his date with Starshine to learn its contents—making Appel’s novel one about the tension between seemingly “inevitable” failure and “the remotest of hopes” for happiness in love, success in enterprise, and immortality in art.

The Biology of Luck is a novel deeply interested in the literary, scattered with references to Washington Irving, Whitman, Melville, Lucien Carr, Norman Mailer, Hart Crane, Jack Kerouac, Truman Capote, and others. It is also the story of a quest, and a journey across New York clearly intended to conjure another Bloom’s voyage through the streets of Dublin, as well as a certain heroic Greek’s homecoming odyssey across the ancient world.

Writing is an act often defined by the conflict between faith and despair, and though Larry is often tempted to give up, the reader will find The Biology of Luck charged with an appealing earnestness and crafted with understated precision at the sentence level. It’s also inventively designed. The novel’s structure alternates between the events of Larry’s day leading up to his date with Starshine and chapters from his novel imagining Starshine’s progress during the same day. On the surface, this technique offers the experience of toggling between two different characters and their overlapping stories, but having been ostensibly authored by Larry, the chapters about Starshine are also (if not solely) extensions of our main character’s writerly compassion and romantic longing for the woman he loves. The ambiguity afforded by this approach is characteristic of Appel’s novel—it’s at once playful and resonant with emotional power. We’re offered a nuanced and sympathetic exploration of both characters, but the nuance and sympathy in Starshine’s narrative also suggest the fullness of Larry’s love, the degree to which Starshine has come to rule his imagination.

Is the novel-within-a-novel conceit—Larry’s attempts to understand and relate to his beloved by imagining and narrating her consciousness—a postmodern technique? I’m far less interested in this question than I am in Appel’s explanation, in an interview that functions as the book’s afterward, that he thought of the novel’s structure as a means of simulating the experience of a love that is itself postmodern: “hyperaware, ambivalent, fragmented. That’s the world of romance that we live in today.”

This same intermittent hyperawareness colors all interactions in the novel. The Biology of Luck—both the novel itself and the other within—is often interested in how people work to perceive each other. As in life, such efforts in Appel’s novel often reveal more about the perceiver than the perceived. Reflecting on “a stunning young woman performing a public striptease…on the fifth story ledge of a residential building” across the street from her bank, Starshine decides that she “loves the girl for all the reasons people love one another, for her beauty, for her vulnerability…but primarily because she sees herself mirrored in another human being, a girl not too much closer to the edge than she is…a girl who could easily be her.”

In perhaps telling contrast, Larry explains why he so dislikes Peter Smythe, a sixty-eight-year-old municipal bureaucrat who’s recently found love online. Larry dislikes him “for the only reason people truly dislike one another, because they are all too similar, because he sees his future in Smythe’s isolated labor and Internet romances. He will age into a leaner, less presumptuous Peter Smythe.” Larry, a chronic self-loather hungry for acceptance and affirmation, finds himself revealed in the most alienating flaws of those he meets.

Starshine’s greatest fear—at least as interpreted by Larry in his novel—is the decline of her youth and beauty, and perhaps their limited ability to impact the world even now, at the height of their powers. Starshine often reassures herself near the end of chapters: “She is beautiful. She is happy”; “She will not lose her beauty. She will not grow old.” Despite her beauty and the burden of anxiety that comes with it, Starshine cannot heal the confused and broken men she meets: an Armenian florist who gives her a lucky pineapple; Bone, the one-armed super who shuts off her hot water when she complains about his impromptu visits; Colby Parker, flattering son of latter-day New York aristocracy; a roguish former activist gone to seed named Bascomb; a middle-aged banker named Hannibal Tuck; our protagonist, Larry Bloom.

But that’s not to say that her charms are powerless. Her beauty and the innocence men associate with it inspire generosity and hope: gifts of money, flowers, charter flights to Amsterdam, a novel. “Please tell me you love me as I love you” reads the anonymous note dropped into Starshine’s postal box. Her roommate scoffs: “That could be half of New York.” The island of Manhattan may be prepared to fall at Starshine’s carefully-painted toes, but her aunt reminds her that she was named for Mussolini’s favorite prostitute, a woman who “died hanging from a meat hook.” Whatever Starshine’s dignity and agency in this world, she is constantly haunted by the specter of time and her physical beauty’s creeping demise.

As the day ends, so does the book. In the final chapter’s conclusion, Larry is reborn with new determination to be the master of his own destiny, to meet Starshine and win her love. But the novel ultimately closes with the final chapter of Larry’s book, effectively extrapolating Larry’s desires: “What better place than Greenwich Village to start a romance, to end a story, to escape?” In closing with the novel that Larry wrote, Appel teaches us that regardless of the endings we imagine, there always remains more that we must hope and more that we must do.

About the Reviewer

David Bowen is a senior editor at New American Press and MAYDAY Magazine, and a contributing editor at Great Lakes Review. His work has appeared in such journals as The Literary Review, Flyway, and Cream City Review, among others. He received his MFA from UNC-Greensboro, and is currently working on his doctoral degree at UW-Milwaukee.