Book Review

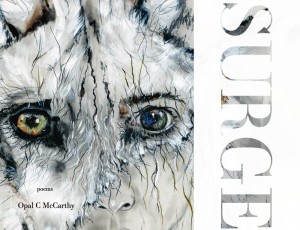

In a conversation for the podcast Commonplace, poet and activist Kristin Prevallet talks about our culture’s attitude toward female sexuality saying, “This culture will—if you express your sexuality [as a woman]—turn you into a goddess, fuck you, and then kill you for it. That’s the cultural paradigm.” Opal C. McCarthy’s complex and many-voiced debut, Surge, explores that process. Surge is both mythic and intimate, centered on girlhood and womanhood as well as the gendered violence women experience in small and large ways every day.

Surge overflows. The trim is larger than standard, the poems are long, the lines are long with wide gaps between words, the content is wildly embodied, and every page spans multiple registers. The book is divided into five sections, each a long poem in itself, with both the opening and the closing sections titled “Girl.” A passage from the opening section feels almost representative of the book:

Mulberry age: my heels stained purpling & raw & then

I kept my blood I took my nourish

through the soles of my feet

I turned away from my mother

furrowed her brow for me

I routed that crick in her back

and maybe I died

my blunt blonde lambent staring

Blood and bodies, especially those of mothers and daughters, are prominent. There’s violence in their living, too, in the way they exist in the world: heels are “raw,” taking “my nourish / through the soles of my feet.” Feet stained with mulberry and a mother with “a crick in her back” feel close to nursery rhyme or folktale, even if the rhythm is blunted and stuttering. Thematically, Surge is reminiscent of Lightsey Darst’s Find the Girl or Rebecca Dunham’s Glass Armonica.

Elsewhere in the book, a flood of voices clamor to be heard—clarifying, obscuring, interrupting, and speaking back to or against one another. These voices are part oracle, part innocent, and part streetwise, sometimes shifting mid-line or mid-page, a prophecy becoming a taunt or a confession:

who taught me

I taught me I taut antenna I thin skinned and scared I assumed the position of scant power lame resistance

I somewhere I

felt an undulation like bodies upon the gears like here I am Lord no doubt no doubt but where was She when

where was my

McCarthy’s language is fragmented and polyphonic, every voice trying to speak at once.

McCarthy may be a poetic descendant of Bernadette Mayer, whose expansiveness and frank sexuality are channeled here. McCarthy’s sprawling lines are also reminiscent of those in Rachel Zucker’s long, messy poems about motherhood. Near the end of Surge, McCarthy writes:

The day she was born you remembered her—

there was not a moment of amnesia

about who she was

The day she was born you wept fluid of every color

emptied out of all your plethora of pain

You emptied your pain to be filled by the sight of her face

There is birth and motherhood in Surge, but not a domestic, daily kind of motherhood. Here, it is raw and uncontrollable:

My girl you do not belong to me . . .

No—only to let us be she & she & she & we & in this wild our voices come

Surge implies that what men fear about women is that mothers can’t exist without sex. Men, the poems argue, want a goddess to sleep with, but in doing so may create a mother, and that terrifies them. The title of Surge’s middle section, “Hetaira,” is an ancient Greek name for a courtesan or mistress, further articulating the book’s mythic themes and complex representations of female sexuality. “Hetaira” begins with sex and closes with motherhood, opening with a passage that ends:

Desire me,

Dark mouth and I will desire you

“Hetaira” ends as a “belly throbs” and a voice says, “myself my womb my waves will rise / as if the first wet light breaking.” Between desire and birth comes the goddess, whom McCarthy describes in one of Surge’s most memorable passages:

One man came into the bedroom wearing: coat hanger angel wings

One man came into my mouth

in the vestibule

throat numb

clove smoke on my lips

He said: don’t all women

have an angel fantasy

I beamed at him glimmering bowed my head

not because I wanted to

fuck an angel

but because I knew it was

my call my pride

to wet his hard praise to lend him our tongue

for his own

mouth

There are several kinds of violence here, from “throat numb” to the forcing of a fantasy onto another person. However, McCarthy complicates the violence only a few pages later:

Don’t forget this:

Adele does ask for it:

Unleashes her will:

In each bed feasts.

The complexity of voices and the expansiveness of the form make an argument that women are as complicated and contradictory as men are always allowed to be, but women endure the burden of men’s expectations.

The fascinating thing about long poems is that they take a form—poetry—that is known for its concision and precision, and then expand it, add to it, and complicate it. Long poems are imperfect, contradictory; Whitman famously revised his throughout most of his life (“Very well then I contradict myself”). Surge adds to this tradition: it is a long poem or a series of long poems and it is imperfect. But perfection isn’t the point. The point is that McCarthy wants to pack in as much as she can, to show the goddess, the fuck, and the violence, sometimes all at once. In Surge, McCarthy announces herself as a versatile poet, willing to critique without, thankfully, feeling the need to comfort.

About the Reviewer

Timothy Otte’s poetry has appeared in or is forthcoming from Denver Quarterly, SAND Journal, Painted Bride Quarterly, Structo, and elsewhere. His other reviews can be found on Hazel & Wren and LitHub. Otte is from and lives in Minneapolis, where he works at Coffee House Press, but keeps a home on the internet: www.timothyotte.com.