Book Review

The philosophical attitude of existentialism so perfectly fits our time, you’d think it was invented for us. Popularized in the twentieth century by writer Jean-Paul Sartre, existentialism is the theory that although we exist, we have no meaning outside of this existence. Therefore, we act in a way that is totally free, but we are also totally responsible for the consequences of those actions. You can see why the term gets bandied about when referring to many of our current problems—population growth, climate change, deranged world leaders—and the depression that sets in because of them. I picture nervous people sitting around a coffee shop, aware of a vague responsibility to act but also not believing a good and right way forward exists. How long before someone in a suit, latte in hand, mutters “get a job” as he slides out the door?

The philosophical attitude of existentialism so perfectly fits our time, you’d think it was invented for us. Popularized in the twentieth century by writer Jean-Paul Sartre, existentialism is the theory that although we exist, we have no meaning outside of this existence. Therefore, we act in a way that is totally free, but we are also totally responsible for the consequences of those actions. You can see why the term gets bandied about when referring to many of our current problems—population growth, climate change, deranged world leaders—and the depression that sets in because of them. I picture nervous people sitting around a coffee shop, aware of a vague responsibility to act but also not believing a good and right way forward exists. How long before someone in a suit, latte in hand, mutters “get a job” as he slides out the door?

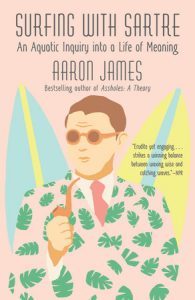

As revealed in his newest book of nonfiction, Surfing with Sartre, philosopher Aaron James suggests we ignore such advice and hit the beach: “This is a book of philosophy. It asks whether the surfer might happen to know something about questions for the ages, about knowledge, freedom, control, flow, happiness, society, nature, and the meaning of life.” If that seems like quite a bit to ask of practitioners of a water sport, James doesn’t demure. If existentialism teaches us one thing, it’s that brains will get us only so far.

So what are the rules for acting more surfer-like in a world careening toward chaos? “Just as we can construct a theory of our sense of justice,” James writes, “perhaps we can draw out and articulate what’s implicit in surfer competence, in what philosophers would call a ‘constructive interpretation’ of the surfer’s practical knowledge.” That knowledge pertains not only to the thrill of riding a wave, but also to the broader practice of surfing itself: chasing down waves, communicating with other surfers, dealing with the days when the waves don’t come. James’s account isn’t so much an approach to a sport as a raison d’être, and to hear him describe it, an inherently sound one considering our current condition.

Central to a surfer’s attraction to a twenty-foot wave is the sense of impotence it imbues, a feeling any existentialist can relate to. “The surfer’s delight comes while he or she is right there in harm’s way, just beyond the impact zone, where a ‘sneaker set’ (of larger than average set of waves) might take you out.” For James, the success that comes from surfing such a monster has nothing to do with dominating nature but instead leads to feelings of “joy, or momentous gratitude, for great fortune.” The world is so big, so chaotic, yet somehow we manage not to be crushed by it. Isn’t that alone cause for “momentous gratitude”? This adjustment in perspective is essential to the capacity of surfer attitude to solve the modern existentialist’s most troublesome dilemmas.

It’s hard not to be enamored by the good vibrations James picks up in the water, but just as compelling are the glimpses he offers into surfing life for those who may never try it. In an attempt to describe the etiquette surfers practice to determine who gets which wave, James offers:

It’s comparable, but still more fluid, [to what pedestrians] practice on a busy city sidewalk. In walking along, we each adjust our walking pace and side steps to accommodate the others, giving way or speeding up, each doing our parts, moment by moment, in a scheme by which each goes his or her own way in a hum of togetherness.

Sure, people sometimes push past, but the system doesn’t break down because of a few unfortunates. This mostly unspoken surfer behavior is just one example of the implicit wisdom inherent in the the practice, which offers us a sporting chance at transcendence in a world where seven billion people all want a shot at the stuff. No one, after all, can own the sea.

There are, of course, those who aren’t likely to take up surfing—non-swimmers; people in Omaha, Nebraska; anyone who saw Jaws at too young an age (that’s me)—but for James, despite his compelling arguments for his particular leisure pursuit, surfing’s hardly the point. The book expounds the practice of any low-carbon-burning activity that offers both moments of high fulfillment and a way for the body to adapt to an awesome and ever-changing world: “A surfer philosophy of life and society holds a convenient truth: life can be better for all of us.” If we must act, why not in a way that offers a break from our daily toil and the massive burden we exact on the environment? I’m all for it. The next step might be to find a way to keep others from complaining about it.

About the Reviewer

Art Edwards’s reviews have appeared or will appear in Salon, Colorado Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, Electric Literature, Barrelhouse, the Collagist, Word Riot, JMWW, Entropy, and theRumpus.