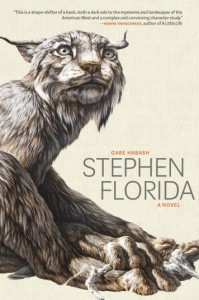

Book Review

Our late adolescent years, those seasons that mark our transition from teen to adult, can be an overcast and eerie stretch to navigate. For some of us, examining those years feels like staring into a murky mirror. Who stares back? What stews in that mind? Reading Stephen Florida, Gabe Habash’s debut novel, allows us unfettered access to those late-adolescent reveries and uncertainties. Narrated by a wound up college senior (misnamed Stephen Florida by a high school-to-college transcript glitch), Habash’s novel brings us derma-close to the surreal waking dream of a desperate young man living in a pressure cooker of obsession.

Our late adolescent years, those seasons that mark our transition from teen to adult, can be an overcast and eerie stretch to navigate. For some of us, examining those years feels like staring into a murky mirror. Who stares back? What stews in that mind? Reading Stephen Florida, Gabe Habash’s debut novel, allows us unfettered access to those late-adolescent reveries and uncertainties. Narrated by a wound up college senior (misnamed Stephen Florida by a high school-to-college transcript glitch), Habash’s novel brings us derma-close to the surreal waking dream of a desperate young man living in a pressure cooker of obsession.

Obsession, though, is an understatement here. Stephen Florida is a college wrestler with one—just one—goal:

My name is Stephen Florida and I’m going to win the Division IV NCAA Championship in the 133 weight class. That’s it. Do you believe me when I say I think about it every day, every hour, at least twenty times an hour?

This singular focus acts as a reverse eclipse, a phosphor-searing light that oversaturates to obliteration anything in Stephen’s life that doesn’t have to do with wrestling. In fact, obsession defines every aspect of Stephen Florida. There are the superficial elements, such as Stephen’s self-flagellating exercise routines, his biblical enumeration of defeated wrestlers, and his hawkish gaze at obstacles he must overcome: wrestlers, injuries, and physical fitness. Then there are the deeper-seated obsessions, manifested as a restless narrative interiority and clinical examinations of his own physiology. This latter tendency becomes a source of great delight for the reader, for Stephen’s bodily obsession finds him recounting details so grotesque they gleefully belong to the realm of “body horror.” Not only does Stephen alert us to the emergence of a cyst or a sudden erection, but he catalogs urine, sweat, swimming cartilage, acne-pocked textures, and all manner of moisture leaking from every orifice imaginable. In perhaps an homage to the master of “body horror,” David Cronenberg, passages of Habash’s novel echo a stomach-churning scene in Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly, as over the course of Stephen Florida the narrator slowly loses a fingernail to his own gnawing: “On Sunday morning, while I’m washing my hands in the bathroom, I notice my fingernail’s fallen off.”

Beneath the dermis of Stephen Florida’s bodily obsessions, we enter the fluid caverns of the narrator’s interiority, where a manic focus on the final wrestling match puts Stephen’s vision of the world increasingly at odds with that of society. This is the classic characteristic of unreliable narrators, a trait we’ve seen in Holden Caulfield, Chief Bromden, and Mr. Stevens. These characters (from The Catcher in the Rye, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and The Remains of the Day) showcase the profound alienation we all occasionally experience, though to such an extreme degree that each of them understand the workings of society as would spacefolk visiting from Mars. Yet, because many of us have experienced similar existential detachments in our own darkest moments, Habash’s narrative provides a line of compassion between Stephen and the reader. In doing so, Habash has curated an empathetic space where we are even allowed to feel compassion for ourselves.

Stephen Florida’s relationships provide an additional calculus for measuring his profound disconnection from societal norms. Yet, in spite of his sociopathic tendencies (he urinates on passersby, runs across town in a gorilla mask, and steals his coach’s journal), Stephen still manages to cultivate an on-again, off-again girlfriend, Mary Beth, and a best friend, Linus. Both of these relationships are marked by the sexual tension and social anxiety of someone trying to navigate human emotions after suffering a tragedy (Stephen Florida’s parents both died not long before he went to college); not only do these relationships feel real and fragile and absolutely heartbreaking as rendered in each vivid interaction, but they provide a glimmer of hope to the otherwise icy and suffocating nature of Stephen Florida’s narrative as he stares down the barrel of his destiny.

A final note: Several times during the first half of the book there are references to whales, a nod to Moby-Dick no doubt:

I saw a massive, ugly whale shored up on a beach, grinning dumbly with its big mouth and its small eyes while fishermen tromped along its back in their boots, stabbing and hacking with knives and hooks in straight lines to make panels of blubber to be peeled, just like wallpaper, the wet sucking noise as they’re pulled off a red-white underflesh.

Perhaps in part because Habash initially clings to Melville’s life preserver of fleshy symbols and sociopathic monologues, the first half of the novel feels overlong. However, after an unforeseen tragedy, the novel abandons whales and Melvillian aspirations in favor of Stephen Florida’s entanglement with Mary Beth and Linus. As these relationships ferment, Habash trades in whales for altogether more mesmerizing imagery like cannibalistic octopi and an absolutely terrifying “frogman” right out of a Lynchian universe. These latter images contribute to a book that is a vivid, visceral experience, filled with all the sweat, blood, and excretions of a postadolescent dream state. It is impossible to exactly describe the magic of this book in a few short lines here, which is perhaps a sign that Habash has written something truly special. Add Stephen Florida to the new canon of unreliable narrators, those outsiders who remind us of our own unknowable depths, and live with us long after we turn the last page.

About the Reviewer

Kirk Sever's writing has appeared in Angel City Review, Unbroken Journal, Rain Taxi, Bird's Thumb, and elsewhere. Additionally, Kirk's work has been recognized by the Academy of American Poets George M. Dillon Memorial Award, the Northridge Fiction Award, and the New Short Fiction Series. He currently teaches writing at Cal State, Northridge.