Book Review

Spleen Elegy’s pastoral landscape is America seen from a Triumph Tiger in fourth gear, passing in flashes and throwbacks. Witness the roadside night fauna: freight trains, canals, livestock, roadkill, and off-ramp silhouettes of “hard-hitting cities” behind black treelines. Then repetitions, reconfigurations. Spleen Elegy organizes them in three sections—“Stitches,” “After Infection,” and “Bethany Dusk Radio”—that present the speaker’s experience of a motorcycle accident, his recovery, and meditation on the nature of memory and selfhood long after the event. Perhaps like all memories, particularly traumatic ones, the relationships between the lyric speaker and observable world in Spleen Elegy are all pixelated phenomena, shifting in and out of focus, hardness. One of Elegy’s blurbs, for example, sees the book as pairing “the good atoms of Whitman’s leaves of grass, and the engines humming their freedom across the highways that cut across those nineteenth century fields.” This is often the case, but Spleen Elegy’s speaker is also a Charles Wright pastoralist, one whose exploration of private mythologies through the recursive external landscape is equal parts Whitmanesque hope and Imagist suspicion. One poem, “When,” expresses the book’s deepest conviction about the pastoral lyric this way: “the delusion of the horse / is another way to say ghost.” If a horse, then ghost. If a train, ghost. If road, ghost. If speech, ghost. Spleen Elegy is Leaves of Grass as a rock-and-roll, information-age ghost story.

Spleen Elegy’s pastoral landscape is America seen from a Triumph Tiger in fourth gear, passing in flashes and throwbacks. Witness the roadside night fauna: freight trains, canals, livestock, roadkill, and off-ramp silhouettes of “hard-hitting cities” behind black treelines. Then repetitions, reconfigurations. Spleen Elegy organizes them in three sections—“Stitches,” “After Infection,” and “Bethany Dusk Radio”—that present the speaker’s experience of a motorcycle accident, his recovery, and meditation on the nature of memory and selfhood long after the event. Perhaps like all memories, particularly traumatic ones, the relationships between the lyric speaker and observable world in Spleen Elegy are all pixelated phenomena, shifting in and out of focus, hardness. One of Elegy’s blurbs, for example, sees the book as pairing “the good atoms of Whitman’s leaves of grass, and the engines humming their freedom across the highways that cut across those nineteenth century fields.” This is often the case, but Spleen Elegy’s speaker is also a Charles Wright pastoralist, one whose exploration of private mythologies through the recursive external landscape is equal parts Whitmanesque hope and Imagist suspicion. One poem, “When,” expresses the book’s deepest conviction about the pastoral lyric this way: “the delusion of the horse / is another way to say ghost.” If a horse, then ghost. If a train, ghost. If road, ghost. If speech, ghost. Spleen Elegy is Leaves of Grass as a rock-and-roll, information-age ghost story.

Whitman, in these poems, is as much horse as ghost—both object of examination and the Spiritus Mundi. This is particularly true in the final section, “Bethany Dusk Radio,” where he figures as a conduit for memory, part of Labbe’s formal architecture of the elegiac. In “Lullaby for Bethany,” for example, the speaker concludes with this evocation:

Don’t wake the miles between our dead and the tower’s red

Walt Whitman sing us a lullaby

that drowns out the chatter of the near-dead

the jingles for obsolete products and that devil of static

Elsewhere—in “Beginning with a Theme by Joe Brainard,” for example—Whitman is the “man of rivers and of every transition / ground to ether,” pixelated, atomized to pure wavelength in a book that is constantly tuning the radio, looking to jam out “that devil of static.” The range of musical allusions throughout Elegy are its AM dial—Captain Beefheart, Wu-Tang Clan, Woody Guthrie, Lungfish, and jazz pianist Bill Evans. In fact, a number of poems, notably “Waltz for Debby,” seem to channel Evans’s techniques—space for contrapuntal license, melodic sequencing, rhythmic displacements—but it is hard not to picture Whitman in the radio tower the whole time, working its red light, fading one track into another like some Transcendentalist daguerreotype of Wolfman Jack in American Graffiti.

I’m drawn to Spleen Elegy’s Whitman, perhaps, because Labbe makes him haunt “hard-hitting cities.” Here I can hear the Whitman of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” whose ebullience in “the impalpable sustenance of me from all things at all hours of the day” is for a moment detached from all those nineteenth-century-looking fields of grass. In Elegy, Whitman’s sustenance is instead drawn “from fire escapes and water towers, / from F train faces and sidewalk chatter.” So is that of Labbe’s speaker, the consciousness that is both listening to and watching the pixilation of phrases, memories, delusions, ghosts, road-artifacts. In “Highway Sweetheart,” Labbe writes:

The dream is to salvage the motorcycle

and ride deeper into the life-size atlas, the plan

I am drawing for a new and unlivable city

of obsolete electronics and broken guitar strings.

I trust this thematic variation on the Whitman lullaby, even though I know I shouldn’t. I suspect that, at turns, the speaker of Spleen Elegy doesn’t either, and knows that my delusion of Whitman is “another way to say ghost,” too.

In “Flung Likeness,” Labbe observes:

Where certain combinations of light are difficult

Walt Whitman is best experienced

on the molecular level. As vapor, as cloud, as the formation

of objects and animals. All is work and near to everything . . .

Here’s Whitman as frequency, as force, as Emersonian truth-value. America. But is there not, as there must be in all elegies, also the nagging consciousness of poetic curation, of arrangement, of the fact that the vital force of the subject is really only present in the speaker’s description? Here’s the “horse,” the vehicle, the rhetorical figure that is as much entangled in “certain combinations” as the speaker is in deliberately choosing his precise experience of light. In “Five Discreet Scenarios with Deep Field Background,” Labbe returns to the “molecular” Whitman, the one who “illuminates / the signal, our midnight vision of a train, atom by atom.” But I suspect the title’s proximity to “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” is no accident. Wallace Stevens is the unseen physicist fusing Whitman’s molecules in Spleen Elegy. Labbe, for one, acknowledges that the beautiful concluding sequence, “Bethany Dusk Radio,” borrows many of its principles and formal themes from Stevens’s “The Idea of Order at Key West.” If Whitman’s a DJ in the Bethany radio tower, Stevens is the apocryphal “Taos Hum,” present whether heard or not, the unexplained phenomenon where the book’s deep lyric work occurs.

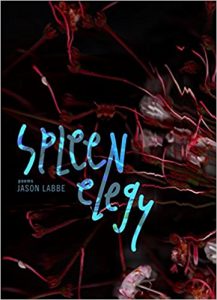

Like Stevens, Labbe is unrelenting in his focus on the friction between metaphor and referent, medium and meaning. The artful curation of the book itself extends this interest beyond the hermetic confines of any given poem. Rather than an author photo, he gives us a line-drawn portrait reminiscent of R. Crumb’s serigraph “Heroes of the Blues.” Similarly, Spleen Elegy’s sections divide—pixelate—with images by the photographer Melanie Willhide, whose work, Labbe tells us, is “often generated on cheap scanners—modified to the extent of sometimes breaking.” Of course, this is an apt metaphor for the literal trauma inflicted on Elegy’s speaker, the Triumph accident, and several of the work’s most striking early poems—“Tattoo Removal,” “A Reception, A Garage, Mountains North and South,” “Waltz for Debby”—linger on the means of modification, the moments of almost breaking. We get to watch the “literal” (re)construction of the lyric speaker from different angles, a machine for remembering that whirs into gear in the last act. “Modified to the extent of sometimes breaking” is Spleen Elegy’s ars poetica of the lyrical body and soul, and the Stevens-like repose that Labbe earns over the course of the book.

In Spleen Elegy’s final poem, “Variations on Stevens with Primary Colors,” Labbe returns to Whitman’s red-light radio tower, but now, he is the DJ:

There is a redder way to say it inside a fading hour

but I don’t know a word of it. If I tell you

transmit all of yellow me while I tilt in a bed of blue.

Red in my ear, in my head, all right all night goodbye.

Not a conclusion, but a means of signing off the transmission with the right doubt, the hard question: Are there ghosts, Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, Jason Labbe, reader? Having assembled the components of Spleen Elegy’s clean machine, what is the soul in this engine? Or ours. And if, like its good horse, Whitman, Spleen Elegy asks us to consider the possibility that there is some “impalpable sustenance of me” drawn from mostly manmade things—say, Triumph Tigers, radios, guitar strings, and other analog relics in “hard-hitting cities”—then it does so with Kerouac’s dictum, and his doubt on behalf of poor all-of-us: “whither goest thou, America, in thy shiny car at night?”

About the Reviewer

Matt Salyer is an assistant professor at West Point. His work has appeared in Narrative, Poetry Northwest, Beloit, the Common, Florida Review, Massachusetts Review, and numerous other journals. In 2016 and 2017, he was a finalist for the Iowa Review Prize. His first collection, Ravage and Snare, is forthcoming from Pen and Anvil Press.