Book Review

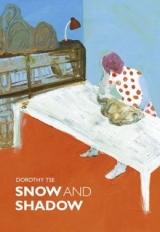

Fabulous, surreal, absurd. Had this collection been published when Robin Hemley and Michael Martone were gathering their selections for Extreme Fiction (Longman, 2003), a collection of the best nontraditional stories of the modern age, Dorothy Tse, one of Hong Kong’s most acclaimed young writers, might well have been among the authors included. Her accolades include the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature, the Hong Kong Book Award, Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, and many others. Her latest collection of short stories, Snow and Shadow, translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman, is a restrained—bordering on disinterested—dreamscape that spends much of its time in the realm of nightmare. Tse tells of women who transform into fish, lovers who sever their own limbs in a battle of affection, and a twisted chess-like narrative of incestuous emperors—a tale that seems to mock the very ridiculousness of the stories we tell our own children.

Fabulous, surreal, absurd. Had this collection been published when Robin Hemley and Michael Martone were gathering their selections for Extreme Fiction (Longman, 2003), a collection of the best nontraditional stories of the modern age, Dorothy Tse, one of Hong Kong’s most acclaimed young writers, might well have been among the authors included. Her accolades include the Hong Kong Biennial Award for Chinese Literature, the Hong Kong Book Award, Taiwan’s Unitas New Fiction Writers’ Award, and many others. Her latest collection of short stories, Snow and Shadow, translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman, is a restrained—bordering on disinterested—dreamscape that spends much of its time in the realm of nightmare. Tse tells of women who transform into fish, lovers who sever their own limbs in a battle of affection, and a twisted chess-like narrative of incestuous emperors—a tale that seems to mock the very ridiculousness of the stories we tell our own children.

Reading Tse is like wandering aimlessly through a dystopian world. In “Woman Fish” we experience the steady transformation of a man’s wife into a fish and his fear that she will slip into the lawless backstreets and end up auctioned off at a seafood market. And yet, life continues on in its usual manner, such as when they go out to their favorite Japanese restaurant:

The chef throws a chunk down onto the white counter. His eyes fix on the gleaming silver knife in his hand, then flicks towards her. He presses the blade down into flesh. There is an odd, sharp hiss as he slits it open. Her lips part, but no sound comes out from between her sharply pointed teeth. Her round eyes pop wide, revealing black centers buried in the silver surround.

In the title story “Snow and Shadow” Tse reinvents the tale of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, outpacing the absurdity of the original with unequaled precision in her attention to warped detail. The complexity of her storytelling will leave the reader tracing the characters out on paper to confirm suspicions of incest and inbreeding in a land where corpses pile in the road waiting to be burned by a man named Dumbo. And Snow is no ordinary princess:

Snow held the corpse of a young girl in her arms, and a pair of scissors in her hand. She had sliced open the skin from the corner of the girl’s eye to her neck, revealing the tissue—scarlet like raw beef—that lay underneath.

“It’s wounded,” said Snow, lifting her blood-smeared face and indicating an animal behind her. It took the serving woman a few moments to make out what it was: a deer with half the skin of its face removed. The woman watched as the princess, with astonishing skill, grafted onto the deer’s neck the resected skin she had just cut from the girl.

When dwarves discover Snow in the forest, they have no idea what to do with her. So they pile animal heads near her bed as offerings. Snow is a vegetarian, though, and nearly starves in their care. When she falls unconscious, they string her up naked in a tree where she is encased in ice until her prince arrives. The parallels to Snow White and the glass casket are obvious, as are the inclusion of a stepmother obsessed with the image of a young woman in a mirror. But the familiar is only sparingly laced into this story of two kingdoms. The rest is a puzzle for which there might be no true answers.

For all the confusion her work invokes, there is something mesmerizing that holds the reader captive. Her confidence in conveying the absurd, as if it is not only reasonable, but understandable that, in “Blessed Bodies,” the men of Y-land would willingly sacrifice body parts for sex until there is nothing left of them, or that birds representing aborted fetuses flood the city in “Monthly Matters,” is enough to propel the reader through her disturbing world.

The hallmark of fabulist fiction is its departure from the expected, and Tse’s work embodies this tradition in every aspect. There are similarities in her writing to Donald Barthelme and his representations of God and religion in “At the End of the Mechanical Age,” which was included in Extreme Fiction. Readers who crave the bizarre—the difficult to make sense of—will find a richness in these nontraditional stories that will bring them back again and again to reread and reimagine Tse’s glorious imagery and subtle references. Our appetite for incomprehension and nightmare is aptly fulfilled here.

About the Reviewer

Heather Sharfeddin is the author of four novels. Her work has earned starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews and Library Journal, has been honored with an Erick Hoffer award and at the New York and San Francisco Book Festivals, as well as the Pacific Northwest Book Sellers Association. Her first novel, Blackbelly, was named one of the top five novels of 2005 by the Portsmouth Harold. Sharfeddin holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is working on her PhD in Creative Writing. She currently teaches at University of Arkansas at Little Rock.