Book Review

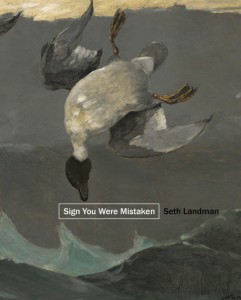

Seth Landman’s first full-length collection of poetry, Sign You Were Mistaken, ranges from the world of dreamscape, of promenading streets, to the ones you love and their palace, your place, and the gaps in-between. This is a book of necessity. Not in terms of our reading it or his writing it (though I believe this necessary, too), but in terms of what is at stake in this unassumingly powerful collection. Necessity is in what becomes the state of being—the world of things and our relation to them. In this collection we develop a sense that necessity is the state of being. And what is the condition of this state? God, Abandon, Dirt, Space’s space, Invention, Aphorism, the Immutable, the Mutations, Appetite, List, and so on. Necessity, of course, goes on. We get thirsty. Our cries are continuous. This is a work of multitudes that is beautiful in its grandiosity as much as in its smallness, its silhouettes. Landman has a wonderful way of not fearing the sacred nor being ashamed of the profane.

Seth Landman’s first full-length collection of poetry, Sign You Were Mistaken, ranges from the world of dreamscape, of promenading streets, to the ones you love and their palace, your place, and the gaps in-between. This is a book of necessity. Not in terms of our reading it or his writing it (though I believe this necessary, too), but in terms of what is at stake in this unassumingly powerful collection. Necessity is in what becomes the state of being—the world of things and our relation to them. In this collection we develop a sense that necessity is the state of being. And what is the condition of this state? God, Abandon, Dirt, Space’s space, Invention, Aphorism, the Immutable, the Mutations, Appetite, List, and so on. Necessity, of course, goes on. We get thirsty. Our cries are continuous. This is a work of multitudes that is beautiful in its grandiosity as much as in its smallness, its silhouettes. Landman has a wonderful way of not fearing the sacred nor being ashamed of the profane.

In this work, we see necessity is as much about presence as it is about absence. At times this comes as a form of potential energy. In his poem, “The Woods,” Landman writes:

Everything still

is running. I might paint.

“Everything” is a bucket of paint held above a canvas. This potential energy eventually succumbs to the gravity of words, spilling paint into Violence, Beauty, Soliloquy, Love, the

Nothing

but the spirit, a slab of mind.

How right this feels in his work. We become splayed in reading. Rawness is virtue.

It is evident too that Landman dwells (the poems often live) on the edge of presence/absence—this hollow that lets thought blossom into sensation—to make the world anew. The prose poem “The Four Questions” is emblematic:

I became lost and did not want a direction….

I carried the quilt outside. An airplane blinked across the sky and I

thought about all of the commandments. How could I dream of them?….

There is a legacy of nothing to understand, said the quilt in letters. You

will build an aqueduct, and you will not be destroyed.

Yes, sensation evokes thought (the airplane evoking the commandments) but thought, in turn, evokes the world of sensation—yes, how could one dream of them? The quilt is prophet—the quilt being the patterned, the tactile, the pieced together, the story-in-stitch that makes the world of legacy and prophecy—the world of creation and sensation. What speaks speaks in letters. Here an object stakes a center for our wanderings/wonderings. The quilt holds, its conceit draws outward. Here, what draws attention demands attention. The distracted mind feels of a tract.

It is (sadly) a rare thing to read love poems today. Landman does not shy away from love. Even if not explicitly about love, the poems breathe love. There is a patience and delicacy to the objects of this world—so much so that at times love is overbearing, awesome, and terrifying. He writes in “Red Eye”:

When there are too many loves, you love love.

This is not generalization, but rather the realization of love.

Landman does not avoid play in this work either—he makes it better. Play becomes the distance a certain violin’s string will bend, giving specificity to its timbre. In his work, the word turns not through sleight of hand, not through illusion, but through investment and a willfulness to stay just long enough in language—language not only as a sonic structure, but as this activity of mind and of feeling. It is this activity that makes his play genuine, that makes the head turn, that makes the eye turn from line to line. Landman’s lines vibrate. He has a timbre all his own.

One sees the realm of edges, of boundaries in this work—again occurring in the mind and in the tactile. Landman’s poem “When Seeing Mattered” (the title implying an edge in itself; sight/sightless, significance/insignificance) is a container of such limits. I am quickened by the transitory state of this poem in particular—the boundary between sleep and waking, silence and speech, town and elsewhere, hearing and deafness, light and dark. This constant turning evokes a mind of Wallace Stevens (here I am thinking of “The Domination of Black”). The nearby tree cries out in Landman’s work, but it is at the edge of town, it is where hearing becomes too distant, too discordant. He lives in the world of abandonment. He writes in his poem “So I Have Communicated”:

I deleted the barn swiftly in the chapter of bullets. I moved on to another thing.

What does it mean to move on? What is it that one moves to? And from? How do we negotiate the mechanism of our travels—the travel of mind to world, of world to world, of world to question; how do we question the question? Emerson writes, “The way of life is wonderful: it is of abandonment.” This collection is full of wonder, of disorientation even in places of exactness. I leave these poems and am beckoned back to them. I take comfort in Landman’s word:

When my life veers, it does not veer. It remains.

About the Reviewer

Grant Souders is a poet and visual artist living in Iowa City, Iowa where he is an adjunct professor in Creative Writing at the University of Iowa.