Book Review

The persistent species of poem known as the “self-portrait”—hardy, it would seem, as the Pacific eucalyptus, as enduring as the horseshoe crab—has drawn its lifeblood since its inception from a certain vein of irony that has managed to endow the species with more than narcissistic interest. One of its earliest specimens, Rilke’s “Self-Portrait, 1906,” frames the poet as the picture of humility, “most comfortable in shadows looking down,” “never in any joy,” Rilke says, of “a firm accomplishment;” yet the poem, a sonnet, ends with an image of the poet looking as if “from far off, with scattered Things, / a serious true work were being planned,” a work, of course, that is the poem itself. Rilke’s initial humility here, ironized by the flourish of the ending, serves as a kind of wink-and-nudge culminating gesture, pointing, as if far in the future, toward an aesthetic achievement the poet has just now, in fact, accomplished.

The persistent species of poem known as the “self-portrait”—hardy, it would seem, as the Pacific eucalyptus, as enduring as the horseshoe crab—has drawn its lifeblood since its inception from a certain vein of irony that has managed to endow the species with more than narcissistic interest. One of its earliest specimens, Rilke’s “Self-Portrait, 1906,” frames the poet as the picture of humility, “most comfortable in shadows looking down,” “never in any joy,” Rilke says, of “a firm accomplishment;” yet the poem, a sonnet, ends with an image of the poet looking as if “from far off, with scattered Things, / a serious true work were being planned,” a work, of course, that is the poem itself. Rilke’s initial humility here, ironized by the flourish of the ending, serves as a kind of wink-and-nudge culminating gesture, pointing, as if far in the future, toward an aesthetic achievement the poet has just now, in fact, accomplished.

Yet the portrait—if indeed it is that—is hardly as coherent as an initial reading might suggest. Is Rilke’s cagey self-description here actually the “serious” work that the ending announces? And how “true,” by the way, can such a portrait be, since its speaker proclaims, in Rilke’s characteristically luminous style, that he’s only “comfortable in shadows”? Just what kind of self, exactly, are we looking at here? Like its descendants, Rilke’s self-portrait seems blurrier with every brushstroke, less portrait, we might say, less stable, painterly mimesis, than a kind of ignus fatuus, flickering and dancing in its frame yet receding each time we approach it. “Self-portrait,” it would seem, is never exactly that.

While poetic “self-portrait” probably pre-dates Rilke—one thinks of Sappho, perhaps, as our earliest portraitist—the genre began, as its name suggests, in response to the visual arts, rising to distinction as part of the modernist adaptation of painterly technique to poetic production. Like modernist painting, the poetic self-portrait refuses a unified image of the self, representing identity not as fixed and coherent but as fleeting and contextual, open to reinvention, perceivable, like Picasso’s musicians, from a multiplicity of angles. Its genealogy, then, is not so much Van Eyck’s stolidly straightforward Portrait of a Man in a Turban as it is Velázquez’s Las Meninas, with its vertiginous mise en abyme, or Botticelli’s Adoration, where the painter appears at the birth of Christ—in an hilariously lavish gold robe no less—flanked by almost the entirety of the Medici family, his patrons. Though the painterly self-portrait emerges during the Renaissance alongside a renewed, humanistic interest in the individual subject, there has always been something more playful in the genre than mere self-portraiture, always some element of humor or irony in these often tongue-in-cheek efforts toward self-representation.

It is this tradition—of play, of wit—to which poetic self-portraiture responds. We are most familiar with the tradition, perhaps, in Ashbery, where it shows up as a whimsical refusal to portray the self as anything more coherent than a set of shifting propositions, hypotheses that form and reform and that disappear, as David Perkins puts it, “in the very process of being proposed.” Ashbery is often described as the “postmodern” poet par excellence, and indeed the term seems fitting for a poet whose style incorporates, among other sociolects, the language of corporate memos, news reports, psychoanalysis, sports, science, literary criticism, and—appropriately—Renaissance painting; but in Ashbery’s variegated, richly heteroglossic linguistic play, we hear the death gasp of the modernist self-portrait, a project—arch, evasive, at times glib—whose self is nothing so coherent as an “identity” but a tissue of languages stitched together and walking around—self-portrait as Pinocchio?—like a real boy.

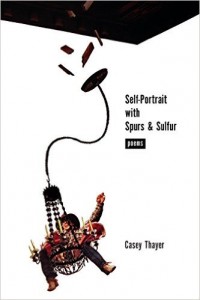

Of course, the self-portrait is far from dead, as even a cursory survey of today’s literary journals attests. Indeed, a veritable cottage industry exists whose workers seem to be churning out poem after poem with titles like “Self-Portrait as Wikipedia Entry” and “Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath’s Braid.” What began, however, as a philosophically motivated endeavor to think across aesthetic media has devolved for the most part into mannerism, into a predictably arch genre whose two-word carte de visite—“self-portrait”—serves as a ticket-of-entry these days into nearly any mid-level literary marketplace. But while the present collection—to which I am very slowly slouching around—sometimes descends into this kind of tartuffery, Casey Thayer’s Self-Portrait with Spurs & Sulfur is ultimately a refreshingly keen take on the parody of self-portraiture itself, a smart, deeply felt intervention in the contemporary genre—and in the rich historical tradition—of the poetic self-portrait.

Half farce, half tragedy, Self-Portrait with Spurs & Sulfur is a kind of spaghetti-western love story centering around the shotgun marriage, and eventual separation, of two characters straight, it seems, from a Tarantino film, their lives a heady mix of pills, pickup trucks, high-powered rifles, cigarettes, snake-handlers, and backwoods church revivals. Yet the narrative here is a relatively loose one. If the collection’s three sections begin each with a prefatory prose summary—think of the “Argument” in eighteenth-century religious and philosophical texts—those summaries are not so much accurate descriptions of what follows as they are coy allusions to the faintest outlines of plot. Here’s the second section’s: “In which disaster hits & her body betrays her. He becomes a cattle brand, then an apparition. She tries to burn off her foot with a bucket of ice. Instead, opens up her bed.” Suspicion of narrative, of course, is a by-now standard characteristic of associative poetry, poetry that sees in narrative a disingenuous simplification of our twenty-first-century lives. But Thayer’s abstraction here is more than just whimsical obscurity, for central to the project of Self-Portrait . . . is the idea that the narratives by which we construct a self are always—and necessarily—multiple, always abstract cubistic perspectives on that irreducible kernel of identity they attempt to describe.

The central narrative arc of Self-Portrait . . ., then, is cross-cut by a proliferation of stories, myths, alternate endings, legends, fairy tales, and B-sides that attempt, cumulatively, to capture a fugitive self characteristically resistant to poetic representation. In these pages are Samson, Pandora, and Narcissus. Over here is Frida Kahlo. Here, Sarah Palin. And here, too, are the sundry objects of western life that stand in as self-portraits of Thayer’s speaker—saddles and cowboy hats, cattle brands and riverbeds. In “Self-Portrait as Stetson Hat,” for example, the eponymous object speaks in a language—half parodic, half Rilke’s true, serious work—we will by now recognize as the quintessence of ironic self-portraiture:

I complete the costume, my open-mouth O,

my silk lining that makes a good photo holder.

Hey, come fill me up with whatever you own.What is devotion if not an openness to be used

in a range of poses: for shade, for sweatband.

To serve upturned as your cup of last resort.

Let me be more than what I’m made for.Ironized as a ridiculous costume, yet charged with emotion and sexual energy, Thayer’s Stetson asks us to attend to the ways in which objects, too, come to image the human psyche. For all our concern with identity and interiority, that is, Thayer suggests here that humanness itself might best be understood as a kind of costume, a uniform to be taken on—and cast off—depending on the context. If self-portraiture begins by drawing a frame around that which is other, Thayer attempts to think beyond this boundary in Self-Portrait . . ., refusing hard and fast distinctions between people and their things; though he is not, I don’t think, an ecopoet, Thayer’s positing of a continuum of life between objects and humans puts him in dialogue with contemporary ecocritics like Bruno Latour and Jane Bennett, invested as such thinkers are in redefining what constitutes a self—what deserves portraiture, we might say, and what gets relegated to still life.

This is not to say that the human is a secondary concern in this collection, for part of Thayer’s delightful complication of selfhood is his simultaneous mythologizing and parodying of the genre of the western, a mode whose characters he both reveres and ridicules in his own wild, pseudo-western romp. Thayer’s protagonists—reminiscent, to a degree, of Harrelson and Lewis in the Tarantino-scripted Natural Born Killers—struggle to overcome the poverty and violence with which they’re surrounded, their lives, as Thayer renders them, deeply moving yet ridiculous at the same time. The collection’s strongest poem, “Anti-Epithalamium,” describes the couple’s separation after the death of their unborn child. “We unmarried,” Thayer writes, “the minute the doc brought the boy back // to us in his hands like a limp sack, untied / by that grief.” And earlier:

we unmarried in the infinitive:

to mislead, to miscarry, to kiss the steel

muzzle of a gun before kicking the door inon no one, the unmarriage of hair, of him,

of him & her. . .This last passage, especially, is striking for its ability to move between pathos and parody, to “code-switch,” we might say, between wildly disparate linguistic registers. Thayer’s allusion to stock cinematic technique bespeaks an ironic yet highly seductive imagism that runs throughout the collection. In “Rehab is for Quitters,” for example, the speaker “palm[s] the stick shift as the canyon // gapes along the strip of highway, shocked / and wide mouthed. St. Christopher swings // the neck of the rearview.” As earlier poetic self-portraiture looked to painting for its inspiration, Thayer turns to film, his kitsch imagery re-investing the cliché with the power to arrest us. Everything, to be sure, is dusty in this collection. Everything—objects, people, landscapes—is well worn. Yet Thayer makes things shiny and new again; or—to re-vitalize my own cliché—shiny and sharp, capable, like spurs and sulfur, of snapping us out of our dulled modes of perception.

Another way of saying this is that at a moment when much contemporary poetry seems characterized by an uncritical, sometimes indulgent lyricism, Thayer’s language ironizes that lyricism, treating lyric itself as a subject, a mode to be turned and turned again on the wheel of his wit. In “Trying Not to Love You, Sarah Palin,” Thayer walks a razor edge between love lyric and political parody, writing that “I try // not to love you, Sarah Palin, but dogs / in every country standard die and I // get teary-eyed.” The end of the poem nicely encapsulates Thayer’s tonal range:

If you’re listening, let me carriage you

to the End of Days in my pickup,gun down moose for food as weeds overrun

the Capitol and the oceans choke usslowly down. At least consider it. You—

the cradle of civilization. Me—the deer skinner,clothes sewer. If I swear to badger the blue

state of my heart, will you please keep me?As this passage attests, Thayer’s tone in Self-Portrait . . . is a sensual one, part Anglo-Saxon earthiness, part Southwestern patois. If at times Thayer is a bit too heavy-handed in his sonic texturing—“with debts of flesh to settle, rage I caged”—this is the easily forgivable fault of a first book, the warming-up of a symphonic voice which promises to enchant us well into the future. In the collection’s opening poem, “Self-Portrait as Saddle,” Thayer’s saddle asks us to “give up the reins for a desperate // grip on my pommel.” What follows is a rollicking, sexually-charged tour-de-force of language, a self-portrait which refuses the glib mannerism of the genre and which shows us, indeed, what a self can be. We’d do well to hold tight on that pommel.

About the Reviewer

Christopher Kempf is the author of Late in the Empire of Men, which won the Levis Prize from Four Way Books and is forthcoming in March 2017. Recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Artsand the Wallace Stegner Program at Standford University, he is currently a Ph.D. student in English Literature at the University of Chicago.