Book Review

Brenda Hillman possesses what many contemporary poets do not: both a political imagination and a poetic conscience. She does what Rosanna Warren says poets should do more often: she “wrestles with the polis.”

Brenda Hillman possesses what many contemporary poets do not: both a political imagination and a poetic conscience. She does what Rosanna Warren says poets should do more often: she “wrestles with the polis.”

Hillman has been an intrepid forerunner for a long time. In 1997, her collection Loose Sugar broke linguistic boundaries, forging an experimental and feminist voice. Her project since the mid-nineties has been to take up each of the classical elements—first earth (Cascadia), then air (Pieces of Air in the Epic), then water (Practical Water)—and to create her unique eco-poetry: words intersect world in its varied political and ecological dissolutions.

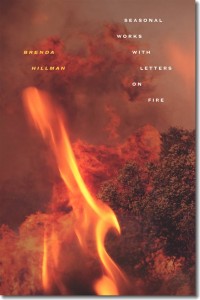

But it’s her fourth book in the series—Seasonal Works with Letters on Fire—that made the longlist for the 2013 National Book Award. This book—yes, every pun intended—does smolder with an inner fire. More so than her last three collections, Seasonal Works has a wise coherence—an energy that embraces the mundane and the sacred. Just read a poem like “Geminid Showers & Health Care Reform” aloud:

Behind the galaxy, there was a flute:

sound was making love to sound;

time was making sound

to sexual, textual, lexical space—

we worked too hard, we lay

near fields from which they gathered plastics—

mimics & contortionists—under the ping-ping

of meteors, under made-up constellations;

the planet flew through space junk

The poem rises sonically, folding us into its rangy universe, reveling the kinetic connections in the friction between words. Yet back on earth—

while the Health Care Bill was being penned

with pens from Chantix, pens from Lidoderm

& Protinix, with pens

from Actos, Lamosil, & Celebrex

—the glad-handing of politicians and lobbyists continues unabated. Hillman’s gift is to mediate between such extremes; in fact, I would venture that in a Hillman poem the mundane is sacred. Both here and in other poems she summons drones and their double-meaning: the bees that are dying away, and the ones that hover, then kill.

Characteristically, for this collection, Hillman draws on a Romantic spirit to conclude the poem, which reaches into an inner space with its final Dickinson-like inconclusive dash:

The sounds fly out, for thee—

we slept as many as the anyway

where meaning met material, that is,

inside the personal,

that is, for love of earth—

Hillman initiates the Romantic spirit in her expansive dedication. She dedicates the book “To Vanished & Vanishing Species” first and “To John Keats & William Blake” second. She doesn’t neglect her children, her husband (“To Bob Upstairs Working”), “People Moaning at Gas Pumps,” squirrels, or various poet friends. And in her tongue-in-cheekily entitled “Ecopoetics Minifesto: A Draft for Angie,” Hillman identifies the Romantics as her guiding force. The poem begins:

A—At times a poem might enact qualities brought from Romantic poetry,

through Baudelaire, to modernism & beyond—freedom of form, expressive-

ity, & content—taking these to a radical intensity, with uncertainty, com-

plexity, contradiction;

Throughout, Hillman invokes a fascinating animism in her poems. As she told me in an interview: “Every single poem has to do with that force: that voicefulness…I wanted to compact these utterances that had to do with the animation of life and letters… literally in words having forceful sensation…to capture the sense of the inner fire, the inner life.”

In poems like “The Vowels Pass By in English,” “Lyrid Meteor showers During Your Dissertation,” “The Fuel of an Infinite Life,” and “To Spirits of Fire after Harvest,” her poems are fueled by the mysticism of Blake. In “To the Spirits” she writes: “when autumn brings a grammar, / wasps circle the dry stalks / & you can totally / see through amber ankles dangling / in dazzle under our lord the sun / of literature—”. By the end of the poem, we do not doubt that Hillman’s vision is as mystical as Blake’s when he saw angels perched in the boughs of a tree.

Although the collection shows us that Hillman has a Wordsworthian way of seeing “into the life of things,” the poems can also be crisply funny. In fact, the placement of the word “totally” in the passage just quoted slyly wards off inflation. Hillman may be expansive, but she constantly surprises with her quick flashes of humor. The “mixed-genre” poem “Sky of Omens, Floor of Fragments” begins with the image of “some mixed-genre insect,” excerpts from a cartoonish graph from the Veterans Affairs website, and includes her quasi-confession: “Usually i don’t melt down anymore, usually / i feel furious enough to take action.” Witty on the surface, she is, of course, engaged in serious political commentary: a government that shows profits in the face of women and men needlessly losing their limbs in a corrupt war. The poem ends with the haunting lines “The spirit guides wait outside the human. / & if in the white cave of this depression / the old wound advanced itself—what then?”

To my taste, some of the political energy in her previous book, Practical Water, was drowned out by details and many of the prose poems lacked the lyricism that we find in Seasonal Letters. The poem “As the Roots Prepare for Literature” fully engages the theme of fire as both creator and destroyer, then becomes elegiac as it addresses this nation’s political, financial, and environmental tumult:

…On streets

named for forts or saints, news is brought

to foreclosed houses. The medicated grasses wait.

In other deserts, soldiers kill other people’s

parents. Here the unemployed wear boots

in cafés near terrifying pies

piled high with cream. Wrens make nests

in cholla. Cylindropuntia fulgida. Spirits

stand round in the bodies of doves.

Hillman has a penchant for including everything: she loves the sibilance and buzz of both creature and machine. The above poem begins: “Sound, what is your muse? Just now / we found a meaning but too soon— / cckkcckk…. Dawn sprinklers start.” As in Practical Water, small photographic images are embedded in the poems. In this book, she plays games with typography; the poem “Foggy Animist Morning in the Vineyard” begins: “—t t t t t t the letters / are lonely, they wait under the vines.” Some may say her diversions and inclusions are excessive and weedy. The block prose poem “Experiments with Poetry are Taken Outdoors: An Essay on Choosing a New Camera” is not one of her more successful experiments and “The Body Politic Loses Her Hair” could use some pruning. “A Brutal Encounter Recollected in Tranquility” which documents the well-YouTubed Occupy Oakland incident that resulted in police violence against Hillman, Hass and college students, to me, is saved by the fantastical ants at the end of the poem.

Yet Hillman’s mystical imagination, her exacting intelligence, and her sensuous play with words on the page often leads to a Mallarmé–like magic. These poems are about vision; like the sinewy forms in Blake’s cosmology, the elasticity of her poems require space, image, sound—well, it’s a whole new universe. Bravely, Hillman will take you there.

About the Reviewer

Amy Pence authored the poetry collections Armor, Amour (Ninebark Press, 2012) and The Decadent Lovely (Main Street Rag, 2010). She’s published interviews and non-fiction in The Writer’s Chronicle and Poets & Writers. She lives with her husband and her daughter in Carrollton, Georgia.