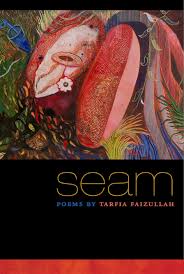

Book Review

Winner of the 2012 Crab Orchard Award Series in Poetry, as well as the 2015 Great Lakes College Association New Writers Award, Seam by Tarfia Faizullah is a stunning first book that defies the conventions of a “first book.” While first books tend to have a theme of exploring and discovering the self, Faizullah also goes beyond the self to write about and translate tragedy, as well as explore the right of a poet to speak on tragedy. Faizullah’s poems focus on the 1971 Bangladesh war through the testimonies of women survivors, as well as the poet’s own family history. Being Bangladeshi American, Faizullah also reflects on her own connection to tragedy, questioning and exploring her own right to tell these stories. Despite the dissimilarities between the privilege of Faizullah’s American experience and the devastation experienced by the survivors of war, Faizullah creates a seam that unites these different lives into one coherent lyrical narrative of the human experience.

Through the introductory poem “1971,” Faizullah sets up her own authority as a poet, as well as her connection and lack of connection to the war. Faizullah establishes her home in Texas, juxtaposed against her parents’ home in Bangladesh—while both exist inside her, she acknowledges the border dividing them, describing the country of her mother’s birth as “a veined geography inside [her].” Born in 1980, Tarfia Faizullah was too young to experience the 1971 Bangladesh war that devastated her family. Despite not being an active participant in the war, Faizullah feels an urgency to understand this history, asking her mother: “Tell me . . . about 1971.”

On receiving a scholarship to travel to Bangladesh, Faizullah explores her ethnic identity through encountering the testimonies of Birangona women, Bangladeshi survivors who were raped and attacked during the war. All the interviews are given the same name: “Interview with a Birangona,” each poem beginning with the question posed to the interviewee. This way, each voice remains anonymous yet autonomous. Some voices are lyrical: “the silence clotted thick / with a rotten smell, dense like pear / blossoms,” while others are more narrative: “I twine a red string / around my thigh. That evening, / a blade sliced through the string.” Some implore the speaker: “Don’t you know / they made us watch her head fall,” while others seem to accept what happened quietly: “Yes, there were others there.” Each poem gives voice to a unique individual Birangona, yet by giving the poems the same title, the testimonies are united into one powerful entity.

Despite the suffering these women endured during the war, they became ostracized from society for being “defiled.” In “Interviewer’s Note,” Faizullah describes: “there are words / for every kind of woman / but a raped one.” Faizullah crosses over this barrier of ostracism, creating a seam between herself and these women. But what is the seam connecting these two seemingly dissimilar bodies?

By exploring the 1971 Bangladesh War, Faizullah wrestles with her own identity as a privileged Bangladeshi American. While her mother and grandmother experienced the war, her only experience is secondhand through family stories. Traveling to Bangladesh and hearing the accounts of the Birangona women, Faizullah confronts her own American privilege, trying to understand her Bangladeshi identity alongside french fries and McDonald’s paper bags. In “En Route to Bangladesh, Another Crisis of Faith,” she confronts her own prejudices:

I take my place among

this damp, dark horde of men

and women who look like me—

because I look like them—

because I am ashamed

of their bodies that reek so

unabashedly of body—

because I can—because I am

and American, a star

of blood on the surface of a muscle.

How does a poet reconcile this “I am ashamed…because I am American” with the “veined geography inside”? Faizullah creates a world where this dichotomy comes together, through the juxtaposition of Birangona interviews with her own responses as an interviewer.

Faizullah creates a separation between herself and the Birangona through clear delineation of the “interview” and the “interviewer.” Faizullah never inserts herself in the interview poems, but allows herself to speak and respond through the interviewer poems. Faizullah not only makes this difference clear through her titles, but also through her use of person. The interviews are always in first person, while the interviewer poems are always in second person, with the interviewee transformed from “I” into “she.”

By keeping her story and the stories of the Birangona in separate spaces, Faizullah doesn’t impose herself into that which she didn’t experience, but also allows for herself to be present and active in the narrative. Faizullah gives space for her own response to these accounts and events, allowing us as readers to see how she both relates to and is distanced from the Birangona women.

That said, it’s important to acknowledge that Faizullah’s poems are translations of the Birangona’s answers. By converting a testimony into a poem, Faizullah has taken some liberty to transform and translate the Birangona’s voices. We cannot see the transcripts from these women, so we are reliant on Faizullah to give us accurate testimonies. Through the act of translation, Faizullah creates a seam between herself and the Birangona: she allows the Birangona voices to channel through her own poetic craft.

Many of the interviewer poems come directly after an interview poem, creating a call-and-response conversation between the Birangona and Faizullah. This is most clearly seen in “Interview with a Birangona” that starts with Question 7: “Do you have siblings?” The interviewee responds to this question, but so does Faizullah through the interview notes that follow. Faizullah reflects on her own lost sibling:

…you want

the darkness she stood against

to be the yards of violet velvet

your mother once cut into dresses

for you, your sister when she was still

alive. Rewind. Play. Rewind. They tossed

me—river—me—

Here, the barrier between self and interviewee becomes unclear, stitched together. We get no transition between the memory of the sister and the interview, except for that turn word “rewind,” which can refer to both the looking back on a memory as well as the literal act of rewinding a tape. In responding to the Birangona, Faizullah discovers a seam that unites her story with theirs: the seam of tragedy.

The title Seam allows for reconciliation of these seemingly impossible connections: privileged America with war-stricken Bangladesh, family history with self-identity, the familiar and the foreign. Throughout the book, the image of the seam transforms and performs diverse functions: seams are divisive, reflections of the self, a sign of abandonment and defilement, and a mark of cultural identity. There’s the reoccurring image of Bengali fabric, the seam functioning both literally and metaphorically. Despite how different Faizullah’s interviewer’s notes are from the Birangona testimonies, the two are seamed together into one narrative. Faizullah, raised in Texas, and the Birangona in Bangladesh create one body.

In reading Seam, the reader is haunted by all these women, all of their stories. Even though most readers may have little to no experience or previous knowledge of this war, the interviews grip at what it means to be human, what it means to be a woman. Even though we may not have had rocks thrown at us, we can still feel the “each day, each night: river, rock fist—”

One of the Birangona asks: “don’t you know / they made us watch her head fall / from the rusted blade of the old / jute machine? that they made us / made us made us made us made us?” The demand of “don’t you know” also reaches out to the reader—don’t we know: the horrific acts enacted on fellow human beings? The use of repetition of “made us” further increases the urgency of the demand. It’s easy for a demand in a poem to become didactic, dogmatic, sermon-like. But Faizullah’s witness to these Birangona women, alongside the vulnerability and honesty in her own personal narrative, creates a powerful testament, challenging us as to be participants against tragedy.

About the Reviewer

Meg Eden's work has been published in various magazines, including Rattle, Drunken Boat, Poet Lore, and Gargoyle. She teaches at the University of Maryland. She has four poetry chapbooks, and her novel "Post-High School Reality Quest" is forthcoming from California Coldblood, an imprint of Rare Bird Lit. Check out her work at: