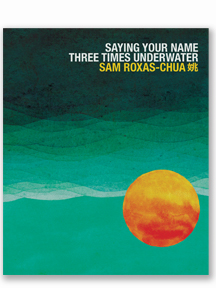

Book Review

In his poem “Puer Before Bedtime,” Sam Roxas-Chua 姚 writes, “I don’t / speak the language of the dead, fluently.” It’s an arresting sentence, one that reverses its meaning entirely with a select, final word. One cannot really speak the language of the dead, though throughout Saying Your Name Three Times Underwater, Roxas-Chua 姚 attempts this seemingly impossible task, while also bridging other, nearly separate, worlds. In his book, he offers the reader access (like Dante) to fantastical places that fill the space between the stanzas and lines of his elegantly imagined poems. Across sprawling spaces belonging to longitudinal coordinates and those spaces that don’t—the Philippines, the depths of the sea, China, our corporeal world, and the one beyond it—the poems act as an atlas, a set of different maps and charts that allow us to explore varied worlds within us, eventually bringing us back to an idea of home.

Sensemaking, the process of assembling shards of memories and elements of identity, plays a large role in Saying Your Name Three Times Underwater. In “Guyots,” Roxas-Chua 姚 describes it one way: “This is how I made sense of guyots. The observing, the asking to step down, the / searching, the orange glow inside a red lantern, the forehead touching forehead.” This inquiry, this patient observation from one angle to the next, leads to a telescoping of perspectives and associations as seen in the lines that continue the poem: “finger / touching God, the healing, the blood as wine, as water, as ether.” This free association, crisscrossing of meaning from one word to the next—finger, God, healing, blood, wine—is a willingness to be guided by the unruly, temperamental seas within us, and what ultimately steers the collection’s compass to its meaningful destination.

The moment of origin in this book, or where meaning begins to unfurl in a myriad of derivatives and directions, comes in the early poem, “Egg Brooding.” Roxas-Chua 姚 starts, “An octopus, miles deep in a bay / covers her eggs for four years, / I don’t know of such dedication / from anything living.” Just a few stanzas later, he contrasts that with:

On my first birthday,

you bit my lower lip

so you would have a story

to tell me about not being yours—

how I came out of a woman

who was nineteen in the Philippines.

And how she left me in the cradle

of a tree limb, unwrapped.

This hatching moment of abandonment and subsequent adoption spawns a self-generative inquiry into identity within the book, which refuses to yield throughout.

As he bestrides far flung worlds, Roxas-Chua 姚 zeros in on the commonality and vagaries in which language naturally inhabits. In “All We Ever Wanted Was Everything,” Roxas-Chua 姚 skips across English, Spanish, Tagalog, Cebuano, and marks of Catholic identity throughout the poem: “The light of Christ, kandila, / sounds like Candle, dila, tongue—” In some ways, it is similar to Li-Young Lee’s poem “Persimmons,” where Lee remembers being chastised for not knowing “the difference / between persimmon and precision. / How to choose / persimmons. This is precision.” These words, for Roxas-Chua 姚 as well as Lee, display both the vagaries and certainties in which language inhabits. If words are delicate gauze, mutable and fussy, then it makes sense that within the poems of the collection, Roxas-Chua 姚 inhabits so many worlds simultaneously.

Roxas-Chua 姚 delights in this word play, writing in “My Last Packet,” “It’s why I write poems. I write for him, my sister, my red / mother, and for our phantom father. All I have to offer are the many octaves of my / emotions on paper, all I have are sunflowers.” These octaves—one word or emotion representing multiple registers—abound within the book. Themes of alchemy and change are present throughout, the mutability of language and identity: “the sailor turned harpist, turned feather—his brother,” as he says in “Atlas.” This poetic shapeshifting is ever present. Of his mother, he writes, “Fathom her / name, urchin her eyes” in a poem of the same name. The word “fathom” is characteristically Roxas-Chua 姚, as it represents both a search for understanding, a mark of measurement below sea level, as well as a nod—1.8 meters is six feet—to symbols of mortality. His note here operates octaves above and below its own original note of meaning.

In a book that travels frequently in origin stories, it is not surprising to see the influence of religion in Saying Your Name Three Times Underwater. The themes of Catholicism in the poems, however, seem less about explicit belief or faith and more about searching for a sense of meaning within a tapestry of existing symbols and myths. In “Iloilo,” the speaker washes the feet of a woman named Mila, which invokes Jesus washing the feet of his disciples. “I wash Mila’s feet. Alone, / to scare away the purple / lines that want to wring / the small necks of her veins.” Mila is a Slavic name, Iloilo is a large city in the Philippines, and the feet washing here isn’t necessarily religious or erotic, it just is. The image is based in religiosity, but it’s also in context with multiple cultures and identities within the poem. It’s an opportunity for the narrator to propel into an origin story, and return back then to Mila’s feet, which he says are “white as stars.” It concludes by tracing the corporeal network of veins, the poem straddling notions of eros and agape, “I now know / blood changes color / from red to purple / as it traverses the veins, / how deep a voice travels / to swallow / a name—beloved.”

If the act of writing is one of discovery, then in a similar way, these poems act like a compass, tracking north, west, sometimes sideways, and even underwater. The poetic compass Roxas-Chua 姚 relies on takes him to far-flung places and ideas—across the natural and supernatural worlds—and he fearlessly charts a course through these disparate ideas of identity, and in the process, seeks to find a common language he can speak, fluently.

About the Reviewer

Dan Varley's essays and reviews have appeared in Mockingbird, the American Interest and the Colorado Review. He is working on a book of short stories and poems. He lives in Brooklyn.