Book Review

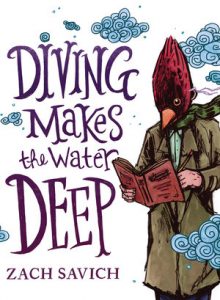

Zach Savich’s recent memoir, Diving Makes the Water Deep, is composed of a series of short, numbered essays within five distinct chapters that don’t try to come to terms with illness as much as they try to make sense of a life spent ill. The way these essays work toward that aim is through the exploration of a patchwork of stories from Savich’s own life, irritated rants about various academic and artistic upsets, bold descriptions of what it is like to be actively in crisis as a cancer patient, and a whole lot of quoted poetry. A section from the memoir’s first chapter, titled “The Disentangling,” perhaps best illustrates Savich’s expert weaving of the varied subject matter at the heart of this book, which includes an example of his thinking about death, family, and poetry:

Zach Savich’s recent memoir, Diving Makes the Water Deep, is composed of a series of short, numbered essays within five distinct chapters that don’t try to come to terms with illness as much as they try to make sense of a life spent ill. The way these essays work toward that aim is through the exploration of a patchwork of stories from Savich’s own life, irritated rants about various academic and artistic upsets, bold descriptions of what it is like to be actively in crisis as a cancer patient, and a whole lot of quoted poetry. A section from the memoir’s first chapter, titled “The Disentangling,” perhaps best illustrates Savich’s expert weaving of the varied subject matter at the heart of this book, which includes an example of his thinking about death, family, and poetry:

The other singular dream I had, the night before my father last lost consciousness: Jake Adam York, the poet, dead several months before, at forty, was waiting for him at a campfire. I woke crying, not because I thought Jake’s spirit was waiting to meet my father in the afterlife but because of how much they would have enjoyed meeting in this life.

Savich uses the form of short essays to create connections in the way a poet might. He juxtaposes the many interests of his mind in a way to better understand the world as a whole—connections between his sickness and that of his father, between poetry and sickness, between the poets he loves and the stories of his friends and family. As the memoir progresses, and its speaker progresses in his illness, the attempts to invoke connection become more important. In the fifth chapter, Savich writes, “Full-time sick. Just days ago I resented the doctor who implied I was nothing but a patient, and now I am grateful for his being ready to be with me in this.” Then, in the following section, “NPR racism, in bubbly tone: ‘There’s a lively debate about whether ISIS and the attacks of September 11th represent Islam.’ A lively debate among idiots.” The speaker finds gratitude for the doctor, returns to the world to renew his fight.

The memoir’s central question seems to be articulated when Savich finds himself in his first poetry workshop. In the workshop, Rick, the workshop leader, has answered the other students’ questions: “how do you know when a poem is done, how do you come up with titles. But not mine: what should poetry be accountable to?” (emphasis my own). In so many different ways, the essays of this memoir are always pointed toward this question, to making some sense out of what a poem—or for Savich, a life—should be accountable to. Savich tries to answer this question by asking, “isn’t it better to prefer complexity, difficulty, the thick of life, even its losses?” but then immediately points out the futility in such ideas of preference: “as though one has a choice, as though preference matters, as though his preference didn’t come from pains I couldn’t see.” I find this statement so interesting because it claims that preference could be the outcome of pains not visible on the surface, and that life is the search to understand the complexities that aren’t immediately glossed in a person, a relationship, a poem, a life. Poetry, the poetry scene—as Savich describes it—often seems interested these days in a sort of simplicity I am uncomfortable with. Diving Makes the Water Deep calls for a greater and fuller picture of the world. It calls for complexity over simplicity. It calls for us to untether ourselves from what we think we know. It calls on the imagination to play its part in creation.

Later, Savich paraphrases another of his teachers, historian Jim Clowes, from the last lecture he gave before dying: “In favor of contradiction, attention, unknowing.” Savich then juxtaposes Clowes’s lecture with a short section on desire and the poetry community. Savich says:

For years I’d earnestly ask friends, after a disappointing reading, when they were excited by the reading, what they loved about it. Out of my desire to desire more. I have stopped asking this question, just as I have stopped thinking that my “community” is everyone who happens to share my interest in poetry, rather than my neighbors, coworkers, friends. Why can’t poets just say “scene” like punk rockers used to? What’s a we.

Savich here elevates the “desire to desire more,” and, implicitly, the desire to know more, and he does so as a poet does so, by juxtaposing competing views and disparate subjects, by thinking hard and boldly about the movement of his mind. He later writes:

The poem says that art can mask suffering? Or that it can convey it, secretly, in a way that exceeds and contains the original volume of one’s cries, while being socially OK, a formal feeling that can get integrated back into any day’s to-do? Today I think it’s saying that we are often abruptly altogether elsewhere, via the ordinary instantaneousness of the imagination, not in a metaphor but in a poem. The orchestral trepanation seems almost painless, though not without suffering.

What does Savich mean by the use here of the plural “we”? We are instantaneously elsewhere through the imagination of the poem. For Savich, there is no difference between that which is learned in the world and the learning that can happen in a poem; the one aids the other and vice versa. As he says, “One writes to find out what it is.” This memoir is an attempt, written in crisis, to do just that—to find out what a life is accountable to, to find out what a life is.

About the Reviewer

Steven Kleinman's poems have appeared in the American Poetry Review, the Iowa Review, and elsewhere. He has work forthcoming from Oversound and the American Literary Review. He lives in Philadelphia where he teaches poetry at the University of the Arts and is a founding member of the Philadelphia Poetry Collaboration.