Book Review

In a voice that is clever, ironic, and feels like listening to an old friend, the narrator of Road Trip, by Lynette D’Amico, offers a raw portrayal of living a life caught between the past and the present. As the title suggests, the narrator Myra Stark describes a road trip—that quintessential American experience that suggests good times and self-discovery in the abstract, but in reality conjures memories of bad food, aching limbs, and breakdowns, both mechanical and emotional. Myra does not follow a linear chronology of either her past or present, but reveals moments of truths and untruths in bits at a time. In the end, various story strands overlap and intersect in often surprising, sometimes disturbing ways, revealing how difficult it is to know ourselves well enough to motor through life with some semblance of happiness.

In a voice that is clever, ironic, and feels like listening to an old friend, the narrator of Road Trip, by Lynette D’Amico, offers a raw portrayal of living a life caught between the past and the present. As the title suggests, the narrator Myra Stark describes a road trip—that quintessential American experience that suggests good times and self-discovery in the abstract, but in reality conjures memories of bad food, aching limbs, and breakdowns, both mechanical and emotional. Myra does not follow a linear chronology of either her past or present, but reveals moments of truths and untruths in bits at a time. In the end, various story strands overlap and intersect in often surprising, sometimes disturbing ways, revealing how difficult it is to know ourselves well enough to motor through life with some semblance of happiness.

Early on, Myra describes herself as getting stuck on the dividing line between squares of a comic strip: “That’s what it’s like. I’m in one box with one set of words and images and then I jump to the next box—different pictures, different text—but it’s the same story.” The narrative structure of the novella reflects this state of in-between, alternating between descriptions of Myra’s own life experiences with her road trip companion and aggravating friend named Pinkie, and the past lives of members of her extended family. In doing so, Myra defines herself by who she isn’t because she does not yet understand who she actually is.

This state of negation is most evident in Myra Stark’s description of her family’s history. In text segments set apart by eerie black and white photographs and simple headings, she introduces the Starks, a Minnesota farming family, first by how and when they died, and then by who they were when living. “Pauline Stark died like a bird in 1951,” great-uncle Frederick Stark died in 1986, Herman Stark in 1960, Buddy Stark also in 1986, and the list goes on. The stories that follow depict the realities of a harsh midwestern farm life. We see a family short on emotions and shorter on luck. When Buddy Stark dies, his daughter JoJo breaks into his dry-docked houseboat and “took everything. She shoved it all in a black plastic trash bag. . . . She had the idea that everything that had gone missing from her childhood was stashed away . . . and this was her one chance to get it all back.” When Pauline’s baby, Benjamin, dies in a freak snowstorm, “[t]hey wrapped the baby in a flour sack and oil cloth and kept him out in the barn while the bigger boys built a coffin and waited for a thaw to dig a grave. Pauline stayed home and washed the kitchen floor the day Benjamin was buried.”

This cold reality is not cruel but necessary. Pauline, the matriarch of the Stark family, is described as stoic and humorless. “On birthdays, the ten or more kids got a handshake and a pair of socks for the boys, and an embroidered hanky for the girls.” There were no birthday cakes or Christmas presents. “Pauline didn’t want her kids growing up soft.” As a result, we begin to understand the box from which Myra has emerged as she moves into her own life and complicated—yet somehow enduring—friendship with Pinkie.

Pinkie, an odd person who carries with her an old stuffed Casper the Friendly Ghost doll and who, not surprisingly, has trouble making friends, serves as the narrator’s foil. Both women are social workers, but Pinkie works with abusive men, while Myra works with the women who have been abused. Pinkie never has an unspoken thought, while Myra hides behind her inherited stoicism. Pinkie needs her routines and analyzes everything, whereas Myra does not want to dwell on difficulties. When both women experience breakups with their respective girlfriends, Pinkie repeatedly asks why while Myra says, “There’s no point in going on when what’s done is done.” And unlike her objective retelling of the past, Pinkie rewrites the past to suit her present narrative. For example, at a sleepover in the seventh grade, Pinkie fell asleep (“I mean, who falls asleep at a slumber party”) and the other girls took her stuffed Casper and “put Band-Aids on his wrists, a noose around his neck, and hanged him from the bathroom light fixture.” When Pinkie bumped into him in the middle of the night she peed herself. Over the years the impact of this middle-of-the-night trauma changes to suit Pinkie’s needs and serves to explain why she has “trust issues with women in shortie pajamas,” “sleeps with the bathroom light on,” and has “a high startle reflex and sometimes dribble[s] pee.” In spite of these differences between Pinkie and Myra, they, like family, share a history, which makes their relationship at times “conflicted and claustrophobic.”

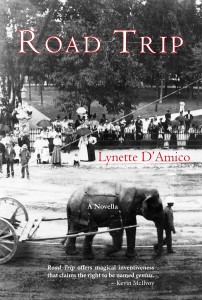

While the events on the road trip with Pinkie seem to be interjected at random points throughout the story, they are central to the development of both character and plot. D’Amico grounds these events with a bricolage of unusual images and sights like road markers: various makes and models of cars, elephants, embroidered handkerchiefs, and a girl made of butter. The significance of each detail is not always clear, but each adds an interesting dimension to the experience, even when its meaning remains mysterious, and seems to be pointing toward a deeper understanding both of and for the narrator.

On this journey to understanding, the narrator is clearly troubled and unsettled. She sees the world as black and white, yet she does not understand her relationship to her past or her present, so prefers living somewhere in between. D’Amico eventually and subtly suggests, however, that there is no way to live in between, and she begins to blur descriptions of past and present rather than separating them. She also introduces a strange encounter with a mysterious woman who seems to prophetically claim, “We all take a tumble from time to time, a header off the bridge, a wrong turn. Sometimes it takes something bigger to change our lives, change how we live, what we believe.” What Myra believes and what we believe is increasingly challenged as we head toward the story’s climax. Revelations of Pinkie, members of the Stark family, and Myra herself begin to belie our earlier understanding of each.

In the end, big events do happen and the road trip with Pinkie comes to a close. Myra does not exactly return home, however, but discovers that her own journey must continue. Like the worn and graying Casper doll she hooks to the back of her beat-up Bronco, her past is forever chained to her. Her job now is to drive recklessly ahead, because only then can she hope to discover not so much where she is going, but who she is along the way.

About the Reviewer

Susan Donnelly Cheever is an English teacher and poet. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts.