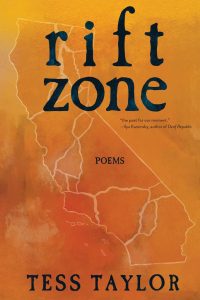

Book Review

From the first poem in Rift Zone, Tess Taylor’s much anticipated third book, the grandeur of tectonic plates are found floating in a cup of cocoa as literal and metaphorical fault lines trace their way through every aspect of life, from the civic to the personal, from the schoolyard to the coastal shelves off Alaska.

The slow break of shifting continental plates and patterns of repeated faults play themselves out in the theater of Taylor’s poems, which become themselves “great fissure where the earth / destroys and births itself.” We emerge from such histories “lately learned,” as Taylor’s poems return us to the landscape written and rewritten, only through poems, through language. Energy builds line over line, mimicking the physical buildup of pressure beneath our feet that will eventually cause the ground itself to shift, while images reverberate like aftershocks throughout the work. These poems seek to create not only space in which to dwell within the fissure, but also to reassemble the pieces.

I retrace so many fragments:

what did I not know was already happening

Ghosts from history are summoned in these poems, drawn into the daily, evoked in details so small as sidewalk crosshairs. Evidence of rift is everywhere, and yet these poems look not just to ruin but to reassembly. What is it to gaze at the point of rupture and will the wound to heal itself? What is it to see this world about to break and have the audacity to hold it together with nothing more than a song and dream of “lungs as cloud as tidal skein”? Perhaps they offer us a pattern by which we too may collect our pieces and move forward in these unsettling days. The poet reminds us there is space for singing these pieces back into a whole.

Then there are the ruptures of our own making, lest we forget—our own violence superimposed on the landscape in the shape of cheap suburban luxuries that persists even as “we stroke their burls / with short-lived hands.” Not all divides are to be gently bridged with dreaming. Cracks separate and defy our efforts at order and taxonomy; everywhere a rift might be lurking. In the poem, “DOWNHILL WHITE SUPREMACISTS MARCH ON SACRAMENTO,” only bones of those abused before lay out any sort of road to traverse in the high country—even if they do “blaze in their graves.” Or perhaps when all is said and done, we will find that which rushes in to fill the rift inhospitable. After all, worlds have ended before.

Whatever can wait waits for uncertain water

The mod suburb beyond us

crumbles already.

I watch an unmoving freeway.

Stalled tankers grit particulate air.

Now, from the ridgeline, I glimpse the sea.

If the temptation is to “each hurry on, not looking,” these poems nevertheless call us to attention. From schoolyard gun violence experienced firsthand as a child to crumbling infrastructure, unstable foundations, neighborhood gentrification, to anticipating having to explain mass extinction to one’s child, no rift is too small, no plate stable. Still, what is this poetic enterprise if not, too, a search for stable ground, as excerpts from the Roadside Geology of California attempt to ground us at the preface of each section. We consider the frame narrative in prose, but what poem is not framed by the poet’s own persistent search for understanding within myriad frames of reference, texts read, objects observed, memories interrogated, narratives visited? “We wrote this book for those friends who want to learn a bit about the geologic foundations of their surroundings” Taylor quotes before section IV. Remove the word “geologic” and we have as true and worthy a premise for any book of poetry. And while these poems are perhaps searching for some kind of stable ground, the poet is gracious enough to let the ruin collect on the page, to allow the reader to sit with her and the pieces of these poems, as in the poem “RAW NOTES FOR A POEM NOT YET WRITTEN.”

The charge is often leveraged, though perhaps less these days, that poems attempting to talk politics have a limited shelf life. Yet we still discuss works such as The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, which could arguably be charged with being “merely” a catalog of the daily, idle gossip and observations from the court of the Empress Consort. And are not our daily lives rife with the threat of white supremacy, school shootings, and the knowledge that this once noble experiment of democracy continues to hold children in cages? These poems do not just speak of the rift, but out of it to declare that we:

Are alive together.

Must now be shields to one another.

& John said: Be a witness.

We brace one another. Plant our feet.

In fog, promise

to stay together.

We will not raise our hands. We are not leaving.

Perhaps we are unsettled. Perhaps poetry offers a language by which we may become, if not settled, at least stable in the unsettling that binds us each along, across, through, and out of the fault lines we must inevitably face. And still there is hope. Still there is singing:

unburied water claims its path

a force acquires

a voice

a valence

also: It sings as it goes

About the Reviewer

Abigail Chabitnoy is the author of How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan, 2019), shortlisted in the international category of the 2020 Griffin Prize for Poetry and a finalist for the Colorado Book Awards. She was a 2016 Peripheral Poets fellow and her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Boston Review, Tin House, Gulf Coast, LitHub, and Red Ink, among others. She is a Koniag descendant and member of the Tangirnaq Native Village in Kodiak. Visit her website at salmonfisherpoet.com for more information.