Book Review

In Karen Leona Anderson’s second collection, Receipt, Adam Smith, T.J. Maxx, and Judith Butler mingle. The first half of the collection is, on its surface, about food and dress. The speaker of these poems is often in a moment of choosing and combining ingredients and clothing, our oldest commodities. The poems, often short lined and intensely punctuated, deftly slide between subjects:

In Karen Leona Anderson’s second collection, Receipt, Adam Smith, T.J. Maxx, and Judith Butler mingle. The first half of the collection is, on its surface, about food and dress. The speaker of these poems is often in a moment of choosing and combining ingredients and clothing, our oldest commodities. The poems, often short lined and intensely punctuated, deftly slide between subjects:

I need to fit

in that satin dress? I need to say what? If I

had coated myself in cream, my in-laws say,

I’d like me better

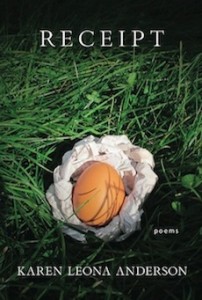

Receipt renders the domestic sphere as not cozy and private, but a place where capitalism, home economies, reproductive labor, and circuits of social feeling collide. Like and need, dress and food—the poems curl around the desires, often in conflict, and what constitutes those desires. The cover image is apt: an egg cradled by shopping receipts twisted into the shape of a bird’s nest.

Formally, the poems are short and grammatically precise (hello colons and semicolons). Rather than taking leap after leap into oblivion, they often fly back to where they started. In the best poems, the staccato syntax clamps down our attention and invites reflection:

Two of me at market: I see Zea,

tinny jewelry and micro-mini, or May,

in cape and dress to her shins; sustained

grain by grain, through, a monoculture.

The poems themselves often end with the let-down of the speaker, the exhaustion of desire among a number of compromised options. We’re delivered into these spaces with a terse kind of brio:

Breathing, heartbeat,

plot in the chart. In the beep that I am

Do you want to go. No. Do you want.

Again, no.

If Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts presents a memorable visceral account of how pregnancy distorts the body, Anderson is similarly unsentimental in her narration of pregnancy as indivisible from financial, existential, and ethical worries and resolves. If “Clearblue Easy ($49.99 CVS)” lists the many obstacles toward pregnancy, the moment of its revelation is wrapped in the wet blanket of a conversation about insurance: “Is it covered, she says as she looks up.” The poems startlingly meet the benchmarks of happy middle-class existence in the backlight of well-founded worry.

The book’s sections “Recipe,” “Receipt,” and “Re” movingly stage the gendered exhaustion of the speaker—the presentation of food, self, home for others—which is constituted by the eternal picking and remixing of elements. “Recipe” diminishes to the stub “Re.”

Anderson’s most challenging poems operate via self-implication in the normative order they seem tired of. One begins with “So, Nature / is not at all that hetero,” suggesting an implicit desire of the speaker to partake of the queerness of nature. However, the poem ends with a startling portrait of the speaker’s acceptance, bound by an erotic charge, of a hetero ordering of the landscape through the tractor:

Friends,

I doubt I can speak of us, actually, without

thinking of the tractor mags he’s so hot about,

his plain black mailbox, my being into it.

And though exhaustion is the arc of the book, it’s not a sour slog. Some of the poems’ most dazzling moments come in representing how this exhaustion is reconciled. “Pizza Night” re-examines this family ritual from the perspective of a “you,” exhausted by meeting the bar of culinary niceness (fresh! organic!), capitulating to convenience. The moment is rendered, intriguingly, as a deep mystery:

All at once you are: needing to feel

full of the worst thing you can

without meaning anything: dark, a star.

Where the first two-thirds of the book tends toward the micro, it ends on the macro. In “Re,” Anderson calls us back to the foundations of capitalism. One epigraph refers to economist Adam Smith, calling to the mind Smith’s assertion that its human nature to truck, barter, and exchange. This is part of the exhilaration in these poems, as the attention moves from the small and everyday—the component—to the systematic:

In the horse

and buggy, in the spinners of the car

that won’t stop and the poisoned river

of bills and coins

These poems are spring-loaded: by turns quirky, tough, and always clear-sighted.

For another perspective on Karen Leona Anderson’s Receipt, see Phillip Garland’s review here.

About the Reviewer

Joseph Hall is a writer, scholar, and a founding member of the bookmaking collective Hostile Books. Black Ocean publishes his collections of poetry. He lives in Buffalo, NY.