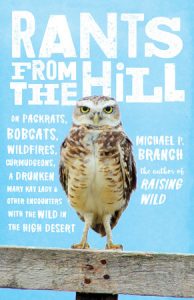

Book Review

Rants from the Hill, Michael P. Branch’s collection of humorous, sly essays is easy to underestimate. Branch has a smooth, disarming writing style that conceals his radical message: in a country overrun by consumerism, environmental destruction, and political decay, making a home in an inhospitable desert is an eminently rational choice. In the introduction, Branch explains:

Rants from the Hill, Michael P. Branch’s collection of humorous, sly essays is easy to underestimate. Branch has a smooth, disarming writing style that conceals his radical message: in a country overrun by consumerism, environmental destruction, and political decay, making a home in an inhospitable desert is an eminently rational choice. In the introduction, Branch explains:

I was not always devoted to the pastoral fantasy of living in the remote high desert of the American West. . . . But I like to think that I have become more focused over time, as I succumbed and committed to the driest and most impossible of pastoral fantasies more than twenty years ago: I am a confirmed desert rat.

For Branch, the desert Southwest is a place of last resort. People “hide” from society in this demanding land of dry creek beds, towering cliffs, scalding heat, wildfires and winter blizzards. We never learn why Branch moved to Nevada, and he offers only a clue in his first essay, “The Ghost of Silver Hills.” Instead of writing about his deep past, he focuses on the present, introducing his home in the eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains as a “desiccated hilltop mercilessly exposed to wind, snow, and fire . . . ,” which was, until recently, nearly uninhabited.

Branch had heard an “unconfirmed legend” of a hermit who lived on his land. In the first two years in the high country, he found no evidence of the hermit. Then, in the early spring of his third year, during a late season snow, Branch, an avid hiker in all seasons, decided to clamber “down a rocky slope . . . [and] crawl into a copse of junipers that was too dense to be entered upright.” After crawling he reached “a small, clear area that was ringed by an impenetrable halo of tangled trees.” He found a circle of blackened rocks that had once been a fire pit, as well as a “tidy pile of short juniper logs that looked as if they had been stacked that morning.” Above this was old rope, which had been used to tie a canvas tarp that was “now buried in the duff with what appeared to be a timeworn bedroll.” Next to discarded bottles of Miller High Life were “surprisingly well-preserved Nixon-era Playboy magazines.” Branch had stumbled upon the hermit’s lair. He muses: “[w]hat would this place have been like in, say, the early spring of 1973. . . . There would be no home within several miles, and it was a twenty-mile walk to the edge of town.” This leads to wider questions of why a person would hide in the desert in the first place. Branch speculates:

Was he on the lam? Or was he, like me, simply a man who had chosen the hills and canyons over some other life? Was his juniper-bowered Mancave an indication of sanity, or the lack of it? Would it be accurate to call him homeless, or was this his true home? Was he trying to get someplace else or only hoping, as I often do, that someplace else wouldn’t catch up with him out here?

Branch does not know the hermit’s motivations. He simply concludes that the hermit had chosen a “perfect spot, the kind of snug shelter where one might well wait out the Nixon administration—or a parole officer or creditor, or draft board, or the millennium, or whatever else might need waiting out.” We can presume that Branch too is “waiting out” something.

Hiding from American society has a long history formally initiated in literature by Henry David Thoreau. Branch is aware of this, and also of the dangers involved with being both alone and suddenly lost in such an unforgiving land, which he explores in “How Many Bars in Your Cell?” In this essay, Branch revels in solitude: “Whenever I am asked why I choose to live in the middle of nowhere, I’m reminded that, from my point of view, I have the privilege of living in the middle of everywhere.” But his long solitary hikes in the desert put him at risk. He states: “One practical problem with being a virtual uninhabitant of the middle of everywhere is that it is an easy place . . . to go out for a stroll and simply vanish. . . . ”

Branch’s wife reminds him of his paternal responsibilities and gets him a cell phone. But it works in only one place: “the very peak of our local mountain, about five miles from home and 2,000 feet above it.” Now that he hikes with the device, Branch realizes that before “getting the smart phone, I rarely contemplated the real risks I run in this wild place; now, because I have the phone and know it won’t work, I worry that this unreliable piece of emergency equipment will leave me vulnerable. . . .” Branch resents this, but there is also a positive side: the phone renders him humble before the dangerous majesty of the high desert “and in that humility I have become more vigilant.” He now packs extra food, water, and clothes, and before heading out, he checks the weather report. He is more aware of the elevation of his hikes and of staying hydrated. Ironically, the phone helps him “enjoy a more profound sense of my own isolation.” For Branch, it is “a sweet liberation to feel the modest rectangular bump in my pocket and be reminded that I am, just as I want to be, entirely out of touch.”

Branch’s collection of essays is humorous and displays a keen sense of down-home profundity. He is aware that as a person nearly alone in a desert, he is in a unique position to criticize the American culture he has abandoned. He is also highly skilled writer, and throughout the book he describes the vast and beautiful landscapes of the American West and the character of those who inhabit it with gentle wit, compassion, and understanding.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Trumansburg, New York, with his wife and two children. His book of nonfiction prose, fiction, and poetry, The Torah Sutras, will be published by Albion-Andalus Books in 2018.