Book Review

We tell ourselves stories to make sense of who we are. While these narratives are grounded in lived experience, they are also shaped by absences and distortions. Memory is artful: the mind’s retrieval of old scenes leads to revised retellings. This process, combined with errors of recall and unconscious fantasy, crafts stories of the past that can feel almost dreamlike. Narratives of trauma seem especially marked by the uncanny or unreal. The traumatized self is haunted by impressions of past harm that shiver out of view, appearing in the present as new panic and dread. In remembering old pain, we experience a partial failure of sight and long for sharper vision.

We tell ourselves stories to make sense of who we are. While these narratives are grounded in lived experience, they are also shaped by absences and distortions. Memory is artful: the mind’s retrieval of old scenes leads to revised retellings. This process, combined with errors of recall and unconscious fantasy, crafts stories of the past that can feel almost dreamlike. Narratives of trauma seem especially marked by the uncanny or unreal. The traumatized self is haunted by impressions of past harm that shiver out of view, appearing in the present as new panic and dread. In remembering old pain, we experience a partial failure of sight and long for sharper vision.

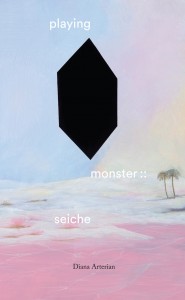

Diana Arterian’s arresting debut book of poetry, Playing Monster :: Seiche, sees all this clearly. Its narrative of family trauma, which reads like sparse, poetic memoir, is concerned with the struggle to recall and make sense of what occurred. Playing Monster tells a story of abuse that the speaker, her mother, and siblings endured at the hands of a monstrous father. The “seiche” of the title—a stationary, standing wave in a disturbed pool— gives image to the book itself as a document of disturbance. Arterian’s language also has a static quality: plain, spare, and exacting. There is often no music in her lines. I don’t mean this as a criticism; the voice that delivers scenes and images to us speaks numbly, as if from a trance—an emotionless residue of trauma. In one poem called “after my mother is granted,” Arterian writes:

full custody

I stop crying completely

I do not cry

for four years

My siblings tell me

I am a robot

with a heart of stone

The affective flatness of the book could be read as anti-lyrical, anti-confessional—pure reportage with the quality of testimony. Of course, however, the book is confessional. Its story is emotional and tells many family secrets. Perhaps it is inaccurate to say there is no music here. In poems which retell specific memories, Arterian’s voice is devoid of embellishment and sonic associative leaps. Yet in other pages that focus on concept rather than narrative, we find transporting lines like these:

Violence is the heart of it

A sure hand all its capacity

Violence whistles sparks The hand

clawing windfire

Poems written from the speaker’s point of view—a “Diana” I assume is the author—are balanced by two other voices woven throughout the book. One voice is the poet’s mother’s, whose 1986 diary entries appear as italicized fragments. These lines celebrate small moments of everyday life and make the abuse suffered at that time more awful in contrast. I found the mother’s memories to be poignant in their cataloguing of the mundane: “A triple hug from the kids for my birthday,” “The girls jumping to ‘Yellow Dog Dingo,’” “Diana walking to pick up William—trying to carry a book and a jack-in-the box.” The other recurring voice in the book comes from newspaper articles about Onondaga Lake in New York in the 1870s through the 1890s, which are repurposed into found-text poems about violent, macabre events. These poems provide aesthetic distance from the personal trauma narrative and seem to suggest that Onondaga Lake, where the poet’s mother lives, has its own haunted history and legacy of suffering.

There are other family voices in Playing Monster too; at times, the book has the quality of a group interview. Recollections and interpretations from the poet’s sisters or aunt are quoted directly and the poet allows their language autonomy and weight. In a particularly powerful piece called “two men yelling,” the speaker describes calling her mother and wanting to tell her what she has been writing about. Instead, the poet speaks more distantly:

I tell her I am writing about

Onondaga Lake

But Diana, she says

you haven’t even been there.

In memoirs about family trauma, there is always the ethical question of whose story is being told by whom. Arterian handles this delicately and fairly, falling into none of the usual traps. She doesn’t romanticize or elevate her own suffering; her voice is part of a chorus.

For a book with so much pain in it, Playing Monster :: Seiche is quick-moving and engaging. The poems are arranged in a narrative arc that builds suspense like a true crime novel with its slow reveal of danger. It begins with small acts of violence and neglect, continues into frightening abuse, and ends with a tentative pursuit of peace. To its credit, Playing Monster :: Seiche offers no perfect closure, no sentimental “and then I learned” takeaway. As the poet moves between remembered dangers and present-day fears, what links the past with the present is worry, just as what connects the speaker’s voice to the voices of her family is sympathy. The various landscapes of the book are similarly joined by feeling. In an ongoing untitled poem, the speaker imagines horrific things happening to her mother at Onondaga Lake, as if the abuse suffered decades earlier in Arizona has followed her to the East Coast. The found-text poems about this same region pull scenes of terror from mundane news reports and demonstrate how a traumatized mind can see threats everywhere. As a whole, the story that Playing Monster :: Seiche tells is one of survival and bearing witness; Arterian’s narrative of damage continues to haunt and hurt. Yet reading the book was an elevating experience—one that reminded me of the power the best art has to give meaning and sight to life’s most difficult passages.

About the Reviewer

Claire Cronin is a poet, songwriter, and doctoral student in Athens, GA. She is the author of the chapbook Therese. Her work can be found in Bennington Review, Sixth Finch, Vinyl Poetry, Prelude, BOAAT, the Volta, and other places.