Book Review

Frederick Seidel has long taken pleasure in the absurdities of everyday American life. Under his scrutiny, the blandness of a chain store—a deeply American sight—becomes hard to distinguish from more scandalous forms of commerce. From “And Now Good-Morrow to Our Waking Souls”:

Frederick Seidel has long taken pleasure in the absurdities of everyday American life. Under his scrutiny, the blandness of a chain store—a deeply American sight—becomes hard to distinguish from more scandalous forms of commerce. From “And Now Good-Morrow to Our Waking Souls”:

The store he’s outside is a Petco,

Closed of course at this hour,

Food and treats and toys for pets,

Leashes and collars

And bondage for dogs.

The humor of that final line is not cheap, serving to make a point: little separates Petco from the aisle where one might purchase a human collar, both being (quite simply) places of business in this business-friendly society. The joke has a sinister bite. For Seidel, the absurdity of contemporary life is never entirely devoid of cruelty.

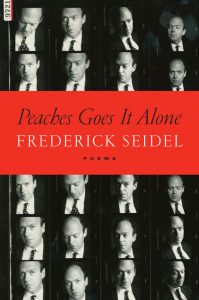

Yet something has changed in his new collection, Peaches Goes It Alone, and that something is the 2016 presidential election. A poet of Seidel’s temperament has needed to confront a problem shared by many satirists: how to reckon with a political scene so grotesque that it has gone beyond caricature. There are poems titled “Trump for President!” and “November 9, 2016” that announce their topicality up front. However, Seidel knows the 2016 election has so profoundly altered American life that even poems unconcerned with politics must find a way to reflect a new reality. “Thanksgiving 2016” makes no mention of the president, yet the title casts a shadow over the poem. Under the banner of 2016, the final lines, addressed to a woman performing a musical number, take on a dire cast: “We listen to you singing / Reasons for being.”

Political poetry always risks self-righteousness, but the best poems in Seidel’s new collection are alert to the paradoxes of this moment, and how such paradoxes have made it difficult to think and feel clearly. The city scene in “Trump” is one such example:

On Emotion Avenue in Queens—

Near Trouble Street—

Cops on horseback clatter

In their yellow slickers

Through the springtime drizzle

Toward Black Lives Matter.

White working-class

Clouds of tear gas

Cloud Emotion.

The pun on tear makes the clouds of tear gas an emblem of how emotions can saturate, rather than clarify, public debate. But emotion is also the very thing that the tear gas clouds. For Seidel, feelings can corrupt when used to overwhelm and thereby prevent deeper emotions from taking root—emotion itself being a vital human response to a world gone wrong.

Throughout Peaches Goes It Alone, Seidel is haunted by the sense that America, as defined by its values, principles, and aspirations, has come to an end. From “Trump” again:

The endlessness of America ends.

And what an ending.

A second-stage booster rocket ascending

From the one below that’s downward-trending.

At the same time—and here we arrive at another paradox—Seidel is conscious that America will not be over, and cannot be over, for those who now live in a far more hostile environment. In “The Ezra Pound Look-Alike,” he concedes that:

The future isn’t over.

Even for the people left out.

It used to be there was no place that wasn’t

Your stepmother making you a pie.

“Even” in the second line reads like “especially.” Seidel’s sense of America as having ended and simultaneously not ended leads him to view the United States as a zombie world, a ghost of its prior self. One poem about the economic recovery, titled “In Late December,” imagines a funereal Manhattan restocked by a sinister “They”:

They bring back billions of bodies

And pile them in the apartment building lobbies

And repopulate the financial world with the dead

Like a dog bringing back a stick.

History in this book repeats with comical horror, so that in “Generalissimo Francisco Franco Is Still Dead,” the 45th President appears as a patchwork figure of himself and the Spanish dictator:

Franco needs water for his golf courses so we can’t complain

Out loud but it’s insane—insane

Monsoons of rain

Drowning the automatic sprinkler systems that maintain

The greens, blinding windshields worldwide, Spain to Maine.

The rhymes accumulate deliriously across five lines, extending a chain from the president’s luxurious golf club to the ecological disaster that will one day subsume it.

There are moments where Seidel admits that he is tired of politics and wishes that he could enjoy distractions without feeling pained by their frivolity. In “Police Cars, Ambulances, Fire Trucks,” for instance:

Oh please! Don’t start in on how bad.

Please. Let me sing that it’s spring.

It doesn’t ruin everything that the president is embarrassing.

Politics takes up a lot of space but

Actually I’m trying to think a long way back

To one of the bridesmaids, who was astoundingly beautiful—

But the dash calls him back. Indeed, the impossibility of maintaining an innocent perspective on the world is beautifully stated in the book’s opening poem, “Athena,” which is addressed to a young child:

Your favorites are the polar bears

Who these days have to walk on snot,

Global warming underfoot.

The child’s point of view, whereby melting snow can be fancifully translated—and thus neutered—into snot, does not hold; global warming asserts itself with capitalized authority at the turn of the line. The danger is not subterranean, but plainly visible if we only glance down at our feet. Seidel’s book prompts us to try and make sense of our new situation, but it does not offer much hope that we will find a way out.

About the Reviewer

Florian Gargaillo is an assistant professor of English at Austin Peay State University, where he teaches modern and contemporary poetry. His articles have appeared, or are forthcoming, in such venues as MLQ, Essays in Criticism, Philological Quarterly, Twentieth-Century Literature, JML: Journal of Modern Literature, and the Journal of Commonwealth Literature. He has reviewed new poetry titles for PN Review, Chicago Review, Rain Taxi, and Harvard Review Online.