Book Review

We know the stories, or we think we do. The Sixties. Bombing in Birmingham. Murder in Mississippi. March on Washington. We’ve heard the speeches. We’ve seen the footage and the photographs. Sit-ins. Hoses. Dogs. Burning crosses. George Wallace making his stand in the schoolhouse door.

We know the stories, or we think we do. The Sixties. Bombing in Birmingham. Murder in Mississippi. March on Washington. We’ve heard the speeches. We’ve seen the footage and the photographs. Sit-ins. Hoses. Dogs. Burning crosses. George Wallace making his stand in the schoolhouse door.

We know the names. Medgar Evers. John F. Kennedy. Robert F. Kennedy. Malcolm X. Martin Luther King, Jr. We know the dates of their assassinations, the names of their assassins and, in at least one case, the assassin’s assassin.

These are big stories. They compose for our country its moral compass—frustrated as it often is. They compose its sense of progress, fortitude, scale. The tenets of our national religion, our centuries-long origin myth, complete with its lengthy list of the heroes and villains who created us, who made us, through battles we paint on the sides of our buildings, who we are.

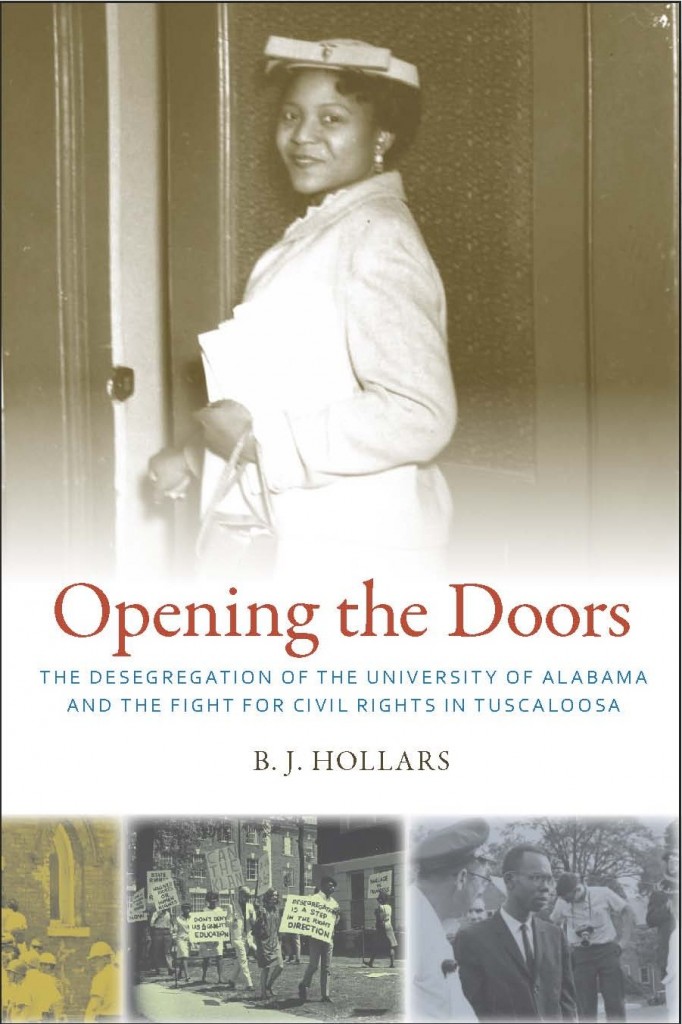

And yet, on the morning of the forty-eighth anniversary of James Hood and Vivian Malone’s National Guard-assisted entrance into the University of Alabama (an image made famous to a new generation by Forrest Gump, though now even Forrest Gump is relegated to the annals of film history), B. J. Hollars and his wife are the only ones present at Foster Auditorium. “Today,” he writes, “we are just two people walking a dog on a beautiful Saturday morning in Tuscaloosa. There are no celebrations, no vigils, no moments of remembrance.”

And yet, Lurleen Wallace Boulevard provides “an invisible demarcation line that to this day separates blacks from whites…” And yet, when Hollars projects “the grainy black-and-white footage from June 11, 1963,” to his African American literature class, their “jaws [drop],” their “eyes [widen],” and one student asks, “This happened here?…At our university?”

In a recent interview, unrelated though applicable, author Rabih Alameddine said, “Sometimes I think that in this country—and in the West in general—we get one idea of a place and it sticks. We can never see the multiplicity of a country or a location or a people…” And this typifies precisely Hollars’s achievement. Opening the Doors is an insistence upon the long second look. Tuscaloosa, Alabama, becomes not that racist southern town trying to keep the blacks out of its university, but instead, and deservedly, a complicated city and people in the throes of social change. A city of multiplicities.

Hollars takes us from Autherine Lucy’s initial attempt to desegregate the university in 1956, which led to rioting and her expulsion, through James Hood and Vivian Malone’s successful though turbulent integration, and on into the years following, which contained some of the largest, and surprisingly forgotten, confrontations in the civil rights movement, including an attack on First African Baptist Church by Tuscaloosa’s police force. Hollars’s interest in this history, as he reexamines it, is two-fold, and appropriately contradictory.

“While Birmingham, Montgomery, and Selma all received full credit for their roles throughout the civil rights movement,” Hollars writes, “no one remembered Tuscaloosa for anything more than George Wallace’s 1963 stand…” Likewise, many of the town’s crucial figures, neglected in other histories, here receive their due attention. The university administrators whose job it was to integrate their school peaceably. The Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the Tuscaloosa News who took on, in print, not only the less progressive of Tuscaloosa, but Robert Shelton, Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. And of course, Reverend T. Y. Rogers, disciple of Dr. King and leader of the Tuscaloosa Citizens for Action Committee, who effectively mobilized the black community and led them in nonviolent protest. Not to mention the countless ordinary citizens whose voices Hollars features: young activists of the time, college students, business owners, the university president’s wife who stood up to the white mobs gathered on her lawn, the barber who washed the eggs Autherine Lucy had been pelted with out of her hair.

“While much of this narrative features nationally recognized figures,” Hollars writes, “Tuscaloosa’s civil rights history belongs foremost to the city and its people.”

But while Hollars emphasizes Tuscaloosa’s importance, he goes to great lengths not to mythologize. Whether it’s the circumstances surrounding the death, and likely murder, of T. Y. Rogers or the writing of James Hood’s controversial opinion piece, published in the school paper shortly after his admittance to the University of Alabama, Hollars opts for gritty complexity over the polish of grand narrative.

The example of James Hood is telling. Had he simply disappeared, in life as in Hollars’s book, after performing his part on the national civil rights stage, Hood would have become legend. His name would have been fastened to one significant act, and for those fighting for equality in Tuscaloosa, a talisman of sorts, a movement’s inciting incident. And while Hood has likely scaled to these ranks in the national schema, if only as a vague and nameless figure of discrimination overcome, Hollars refuses to consign him to abstraction. Because Hood did not take a graceful bow and go quietly to class. Instead, he wrote the following for the Crimson White:

Why doesn’t the negro race wake up and go about this thing in a more intelligent way?… It is my firm belief that through the process of education the sit-ins and swim-ins will be unnecessary. There must be more time spent in the classroom and less time wasted on picket lines.

The dips in Hood’s logic hardly need parsing, though as Hollars argues, the editorial was less intended as a critique of those still on the other side of Lurleen Wallace Boulevard as it was an attempt to further insinuate himself among his white schoolmates. Of course, the black community did not respond well, and finding himself caught somewhere between social movement and status quo, Hood left both the school and Alabama within months of his triumphant entrance. Not the way we remember it, but the way it happened.

I often found myself fighting Hollars’s history, or rather, fighting myself as I read Hollars’s history. I did not want Hood’s editorial or its consequences to alter my conceptions of the moment, nor did I want to read of the petty jealousies and contentions among the leadership of the civil rights movement. Nor did I want to find myself, given the brutal tactics of so many of the region’s law enforcement officers, sympathizing with the frequently reasonable Police Chief William Marable. Here was a man who, according to his son, spoke of and treated everyone as though he were “introducing me to the greatest people in the world,” and who worked closely with T. Y. Rogers, often with mutual respect, to coordinate lawful marches and demonstrations. Yet he also allowed, or couldn’t prevent, his police force’s bloody attack on First African Baptist Church and the subsequent mass arrests, which included T. Y. Rogers’s arrest by Marable himself.

This is getting too tangled, isn’t it? Governor George Wallace, for instance, is supposed only to be the villain, or at the very least an unscrupulous politician, not, as it turns out, a figure of redemption. After being confined to a wheelchair “due to a failed assassination attempt in 1972,” Wallace alleged to have found God, confessed his wrongs, and did what he could to make up for them in his final term. Later, he would attend a ceremony awarding the first Lurleen B. Wallace Award of Courage to none other than Vivian Malone—the infamous George Wallace, whose funeral was attended by approximately twenty-five thousand people, half of whom were black, and one of whom was James Hood.

“[There] are no villains here,” Hollars writes, “merely people who believed what they believed due to an amalgam of experiences, traditions, and geography.” But more fascinating than the discovery that our country’s darker figures are not always so easily sorted are the unexpectedly modest responses of many of the period’s heroes.

Jefferson Bennett, then assistant to the university’s president, drove the getaway car that rescued Autherine Lucy from a violent mob of two to three hundred, yet when asked about the incident decades later, “he refused to credit himself with acting beyond the call of duty and reacted with great disappointment for what he viewed as the administration’s failures…”

Of her first and only day of class, Lucy says, as though it were not the accomplishment it was, “I just walked through and smiled and said, ‘Excuse me, please’…”

Of his editorial endorsing desegregation, which led to numerous death threats, Crimson White editor Mel Meyer says, “The truth of the matter is, I got put into this whole thing…not because I was a passionate person for the cause, but just because I agreed with it.”

And when college student Donald Stewart noticed that James Hood had been eating alone in the university dining hall, he decided one day to sit with him. Hood would later consider this “a fairly significant and courageous act,” but according to Stewart, “it was just something I did.”

Even T. Y. Rogers’s wife would say of her husband, “I couldn’t say that he really emulated King—because that has to be a gift from God—but [Rogers] most certainly was in sync with all of his ideas.”

A history, then, with no villains. And with heroes who, despite all evidence to the contrary, do not consider themselves heroes, perhaps wishing not to corrupt, due to whatever self-conscious sense of imperfection or commonness, the grand civil rights narrative. And how indeed can one compare to the legends of Kings and Kennedys? A thorny question much deserving of B. J. Hollars’s long second look.

Imperative as it is to remember the warriors and battlegrounds of our past, in particular those long-neglected or wrongly assessed, it is tempting to force distinctions between good guys and bad. It is also a comfort. But perhaps it isn’t the most helpful, or even the most revolutionary, way to examine this history. Thankfully Hollars agrees. Confronted with the very real problems, then and now, of racial prejudice, violence, and socioeconomic strife, it isn’t enough to simply excuse ourselves from the fictitious “bad guy” court—Well, I’m certainly no villain, so I can’t be part of the problem—especially when chief among our problems is political apathy. Perhaps we don’t need to wait around for idealized leaders to make things better for ourselves and others. Perhaps, as Hollars’s book beautifully illustrates, we need only be human.

Published 3/31/14

About the Reviewer

Nicholas Maistros holds an M.F.A. in fiction from Colorado State University. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Bellingham Review, Nimrod, The Literary Review, and Sycamore Review. He is currently finishing his first novel, These Imaginary Acts, and living with his partner in New York City.