Book Review

The abstract painter Barnett Newman had specific instructions for how viewers might approach his enormous canvases. They should stand no more than twelve inches away, so as to feel “full and alive in a spatial dome.” From this intimate angle, the viewer might achieve an ideal balance of foveal vision (used for tasks such as reading) and peripheral vision. Newman’s 7’11⅜” x 17’9¼” painting Vir Heroicus Sublimus (1950-1951), for example, presents to the close-up viewer a garnet expanse that stretches in all four directions. Newman likened taking in a new painting to meeting a new person: “If you have to stand there examining the eyelashes and all that sort of thing, it becomes a cosmetic situation in which you remove yourself from the experience.”

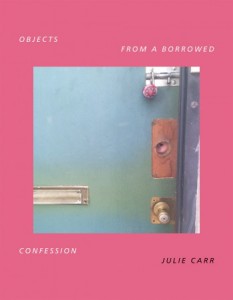

Julie Carr is a poet, not a painter, but readers of her ambitious new collection, Objects from a Borrowed Confession, might well follow Newman’s advice. Don’t stand there examining the eyelashes; take in the whole of this meticulous, exuberant book.

Composed of letters, diary entries, a novella, critical essays, and cinematic scenarios, the book announces its stance against lyric subjectivity from the first page: “But maybe it’s time to let all this go. The naming and the wrestling. (Judgment.) The naming and the renaming of the self.” And on the next page, simply: “Maybe it’s time instead for the giving over of the self.” This giving over is what Newman was after—and what Carr herself (following Jean-François Lyotard, following Newman) expected when she visited the National Gallery some years ago. Lyotard describes Newman’s paintings as “instances of the sublime ‘now.’” But Carr’s encounter with Newman’s The Stations of the Cross that day in Washington DC fell flat (“I tried, almost comically, to experience something at all, but my expectations had been too huge and the room too small.”) Instead, she “wandered around without purpose” until she found herself before A Girl with a Watering Can, which she recalled seeing forty years before. Carr’s visceral responses to Renoir’s painting triggered associations, longings, links to herself as both daughter of a mother and mother of a daughter, as well as further inquiries into what she calls, in Objects, the “other work of confession”: “To see into something that can’t be seen, to name something that has no name, to speak to someone who cannot respond.”

Such a frankly autobiographical moment—describing and interpreting “the way presence breaks in on you”—illustrates how readily Carr toggles between the personal and the philosophical:

One sees and in seeing, deeply attending, one feels one’s “place in history” (again Gelhorn), or to put it more generally, one feels one’s place in time—separate from any origin approaching some unknowable end, distinct from one’s beloveds because one’s beloveds are always distinct. Experiencing my place means I am here, which is to say, not there, not her, no longer her.

Haunted by her recently deceased mother’s present absence, and confessing to “nothing more or less than [her own] aliveness,” Carr enacts what Stanley Cavell calls “a lucid waiting”: in Carr’s words, “to look and feel and wait to see, to be seen.”

One way to see and be seen, it seems, is to reread and reference—that is, to retype. (Carr asks, “Is retyping the words of someone you have lost or are afraid of losing, or of someone you wanted but never had, a way to resist this loss, this never-having?”) Sneakily, titles of Newman’s works thread through the passage quoted above: Here and Now, Right Here and Not There—Here. In this essay alone, Carr refers to or quotes Lyotard and Newman; Martha Gellhorn, art historian T. J. Clark, and Poussin; Augustine and literary critic Gerald Bruns; and poets Amiri Baraka and Alice Notley. Without context, this long list might be off-putting, but there is a pleasing, halting friction in the movement of the other minds at play in Carr’s own mind as these voices come together on the page. To wit:

“The course of real life, biography, gives lasting resistance to the improbable event of your coming,” writes Lyotard or Augustine (it’s impossible to tell) to their god (Lyotard Confessions 13). But then you find yourself standing, emerging out of shadows, arms by your sides, with whatever object you are holding, in her sight.

Others’ ideas strike Carr with “alienated majesty,” echoing and disordering her own thoughts. Borrowing others’ words gets her closer to her own, and vice versa. Carr thus eschews the familiar idea of confession as asking for forgiveness or seeking atonement, and wonders if confessing isn’t, instead, an asking “to be recognized, even, one could say, made?” Harnessing the problem of other minds in the service of what she calls a “‘seeming’ self,” Carr reaches for her ready-to-hand tools: life stories of family and motherhood; “headache journal” and “race diary”; news reports of the deaths of children; poems by John Donne, William Wordsworth, and Jean Valentine. The work-at-hand is ethical and embodied—that dreadful, desirable, difficult acknowledgment of self and of other that goes beyond and presupposes cognitive knowing.

As I was reading Carr I reached for Cavell’s essay “Knowing and Acknowledging” in Must We Mean What We Say?, but in borrowing his formulation I do not mean to deflect, nor to simplify or soften the work Carr takes on. She declares:

There really is no poem outside of fear, no sublime on one page and beauty on the other. To write is to call to that fear, to lie down in it. Or to put it more bluntly, the terror of the un-narratable, unnameable “I” that I encounter in my mother’s mind full of holes, is fucking the beauty I want—the anarchic violent poem.

One “natural fact” that underlies the philosophical problem of privacy, Cavell says, is our tendency to believe that, since there are aspects of ourselves we deem unknowable, we go around feeling we are largely unknown. The situation of the self is desperate. It’s difficult to name our experiences even to oneself, he writes, “because one hasn’t forms of words at one’s command” and because one “hasn’t anyone else whose interest in helping to find the words one trusts”—enter poetry. I like to think that if Cavell were to read Carr’s harrowing and uplifting book, he would see in it the fulfillment of what he takes to be the promise of poetry.

So it’s not exactly that Carr’s project in this book is anti-lyric. Pointed asides to or on behalf of self appear throughout the heady sequence, “Pity Pride and Shame: A Memoir” (a prose “experiment in autobiography laced with fragments of Romanticism” and written “in concert with” Rousseau’s Confessions). In a sequence that takes place in a plane, “with a few hours to unveil the soul,” Carr draws on Gerard Manley Hopkins:

. . . soon we will be landing. I have only begun the stripping, the stripping of matter, the unleaving. “For Christ plays in ten thousand places / Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his / To the Father through the features of men’s faces.” Have belief make an I at least!

The last line is directed to Christ, to Hopkins and/or to the poet herself; in any case, the explanation conveys impatience, nervousness, excitement at the prospect of such a making. And yet, other, parenthetical gestures register reluctance or even shame: “(I commencing.)”; “(Myself I, I am, not seen.)”; “(I am without. Never desire.)” Or pride. As a mother, Carr has brought other I’s into the world; her sick daughter sits quietly in her lap, and the poet thinks, “My I I made.” As do lyric poems, the letters framing the book do double duty as the expressions of narrowly construed personae and as invitations to the reader: “Dear J.,” the book begins; “Love, // Julie,” the book ends, as if we are well within our intimate rights to read over the shoulder of Fred Moten, the addressee of the closing “afterthought.”

But enough with the eyelashes. The scope of Carr’s book (over ten years in the making) must be appreciated in toto. As an object, this large format book is extraordinarily coherent in design. The brilliant use of fully justified text deepens our visual sense of the book as a total package. From this object and through the language it delivers (“language, a condition, not of the person, but of the world”), the poet looks out, gives over, feeling, waiting “to see, to be seen.” We see you, Julie Carr.

About the Reviewer

Cassandra Cleghorn is the author of Four Weathercocks (Marick Press, 2016). Most recently a poetry finalist for the Jeffrey E. Smith Editor’s Prize at the Missouri Review, Cleghorn has work in journals including Paris Review, New Orleans Review, Poetry International, the Common, Narrative and Tin House. Educated at the University of California-Santa Cruz and Yale University, she lives in Vermont, teaches at Williams College, and serves as poetry editor of Tupelo Press. www.cassandracleghorn.com.