Book Review

Harmony Holiday’s debut collection of poetry, Negro League Baseball, responds to the influence of black American music, thinks through the idea of “the poem as archive,” and makes a space that addresses the poet’s relationship to her father, “his legacy and its impact.” She also uses her poetry as an attempt “to knock down a wall to make space for [her] own adjacent room and acoustic.” After reading the poems it’s clear how replete they are with the various residues of music, but more importantly, how they engage readers to think about how historical placement actually happens.

Harmony Holiday’s debut collection of poetry, Negro League Baseball, responds to the influence of black American music, thinks through the idea of “the poem as archive,” and makes a space that addresses the poet’s relationship to her father, “his legacy and its impact.” She also uses her poetry as an attempt “to knock down a wall to make space for [her] own adjacent room and acoustic.” After reading the poems it’s clear how replete they are with the various residues of music, but more importantly, how they engage readers to think about how historical placement actually happens.

The poet tells us the word jazz “become[s] vapid and spangled through overuse and misuse,” which is why she uses baseball instead. She further offers this reason for its usage: baseball is used

in hopes of conjuring the sense of isolated togetherness felt by me personally within the central relationship in the book and by black people, especially black entertainers and artists, in any endeavor toward forms that do not wish to draw attention exclusively to race, but are forced to in a context where certain idioms of accepted and even encouraged rule-breaking are often seen as scene, or as some nuance of the dialectic between oppression and decadent experimentation.

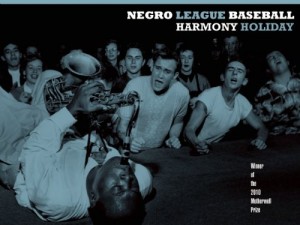

Holiday notes in her afterword, “We need a place to play if we are going to have a game.” Here, however, we observe that the poet is not playing for a white audience as the cover of the book might belie. The front cover is a photo by Bob Willoughby, a certified jazz enthusiast who nonetheless is much better known as a chronicler of Hollywood celebrities. Willoughby’s photo portrays an audience flipping its gourd for Big Jay McNeely, who is on his back sweating and honking a saxophone into the air in Los Angeles, 1951, transforming the crowd into a crazed sea of white maenads. In fact upon first glance you feel the employment of a compositional strategy that is upside down, one that even operates by a logic of segregation.

These poems actively complicate, resist, and turn around those spectating roles that Willoughby’s photo represents. The poet claims / reclaims a right to be her own chronicler. She does this by saying what jazz means to her and inciting her readers to ask themselves these questions: who receives a piece of art and how is it transmitted, by who, to who, and for what?

It turns out these are no small questions, especially as we move through an age of tabulating information, recording it, remastering it, and preserving it against a background that on many days just gets in line for the corporate-minded siren call of clear-cut ownership or finds it easier to play to a Ken Burnsian summa narrative. Holiday’s poetry, in contrast, incites the reader to think about transmission; when you inspect the interior flaps of the book, you even find an extended meditation on bassist Charles Mingus, incorporated to make a critical space where Holiday explains the import of archives, race, and music to her writing.

Her poems are chronicles that frame their own engagement; in terms of Holiday’s kinetic, long line of hybrid prose, it seems the page moves toward bursting. Duets of intelligence course through their “patient assembly.” In these poems “the season grooves” to the count of music’s upheaval: “Sinking pulse and rope beat. While “Empire, so lonely” is droning on, “Saxophone around soaking bounty” is remembering how “love was earning it.” Wait for an appearance by Josephine Baker or Lead Belly or Abbey Lincoln. “I’ve set my seek above,“ the poet says.

To move toward acoustic rooms where “a whole city clamors crimson disturbance.” We listen to accruals of biography and microshifting assemblies. Hooks of music exist in a background where one moment it’s “pursuance turning nuance to itself” and the next a “mummied map of the family album where your gauze is August sun vapor on sparrow wing pavement.”

Language wildly extends into “a cistern of earned desire.” As you read, notice the vestigial countdowns, the refrains. The poet reveals personal epistemologies as “whistleblown, colloquial,” so if there is a jukebox at the diner, it doesn’t ask for your dollar, it asks for your “dimelemon.” There is a sensual exchange that keeps it all going, going “another round.” One poem can say: “I put honey to your gun seams.” Or say this: a woman who “locates herself repeatedly spends herself on each occlusion.” And say this:

This Diamond Noon, can you, room in me, recede room, pay the fee, the feed,

beast up, and do it again

these againagainagain people, me people, copious minded, believe I’m with my

oath the,

road shaped belly loaded flagrant light of mineral,

though, don’t propose to me on that extraction, but do please say something into

halves and centrics.

An insistent we is dwelling in the pages too—”The things we’d know,” “And we compensate”—it’s a collective voice. One phrase begins, “We are proximate.” Here I think Holiday is pointing to ways that a single pronoun can suggest the double labor of articulating one’s placement within tradition but also the willingness to sidestep it. At times it is better to avoid the archivists’ proclamations and rather hold in doubt the various alters of historiography.

We are proximate, drawing near, moving toward a close relationship, estimating or calculating a position. We think about the semantic play of the word “approximate” as in something coming close to an original; something like a jazz record, for instance, that tries at its best to be a faithful document of the playing. Or in this book we think about how documents are packaged and circulated and what kinds of omissions reinforce a dominant narrative.

Harmony Holiday is tuned to this testament of dissonant transmission. “[A] huddle of disclosures play the page and the romance I’m left with is this knack for the music of unconditional departures.” I sense though that her poems amass their own body. They effectively archive themselves, which is why I’m inclined to think that the poet plays for herself in the same way that Big Jay McNeely plays for himself. Holiday is tearing it up. That’s what seems to be the real “Saxophone around soaking bounty.”

About the Reviewer

Collin Schuster is a poet who lives and works in Baltimore. You can find some of his other reviews online at 360 Main Street and The Rumpus.