Book Review

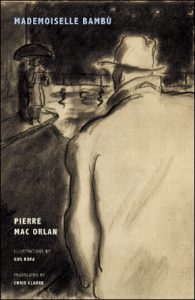

Merging crime, espionage, and absurdist fiction, French author Pierre Mac Orlan (born Pierre Dumarchey in 1882)—a prolific writer of adventure novels, erotica, songs, essays, and memoirs—constructs a compelling novel of intrigue set in the murky shadows of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Written in stages over the course of decades, Mademoiselle Bambù comprises several pieces of writing, revised and consolidated into a single volume and reprinted in English with exquisite, original, sketch-like illustrations by Orlan’s friend, Gus Bofa, an artist who is best remembered for his book illustrations of French literary classics and his collaborations with Orlan.

Merging crime, espionage, and absurdist fiction, French author Pierre Mac Orlan (born Pierre Dumarchey in 1882)—a prolific writer of adventure novels, erotica, songs, essays, and memoirs—constructs a compelling novel of intrigue set in the murky shadows of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Written in stages over the course of decades, Mademoiselle Bambù comprises several pieces of writing, revised and consolidated into a single volume and reprinted in English with exquisite, original, sketch-like illustrations by Orlan’s friend, Gus Bofa, an artist who is best remembered for his book illustrations of French literary classics and his collaborations with Orlan.

Aaron Peck, in his afterword to the book, emphasizes the importance of Bofa’s contributions to Mademoiselle Bambù in serving to complement Orlan’s moody work and underline the obscure and shadowy characters who populate the story. “His drawings suggest the existential darkness that overtook a Europe defaced by war and modernization,” remarks Peck, noting that “his style is dark, almost resembling the aesthetics of film noir, though at times it is also goofy or playful.”

This handsome edition also features an enlightening introduction by Chris Clarke, responsible for translating the text into English, who describes the author’s particular take on the spy novel as a “poignant example of Mac Orlan’s blending of the social fantastic with the adventure novel and a dark and latent surrealism.” Opting to confine the main narrator’s role to “the odd polite interjection and occasional comments,” Mademoiselle Bambù—which examines the life of Signorina Bambù, a double agent in the service of France, and the diabolical career of sinister spy Père Barbançon—is told through wistful confessions by Captain Hartmann, an adventurer and accidental spy, and through the “observations and fabrications” of Paul Uhle, the odious proprietor of a boarding house in Brittany where Barbançon spends his final days. Philosophical, darkly humorous, and highly original, much of the book’s pleasure is derived from Orlan’s astute, comic observations and his colorful, if sometimes derisive, depictions of the larger-than-life main characters.

Hartmann is introduced to us in his early sixties, residing at a luxury hotel in Hamburg. Expensively attired, with a face the color of gingerbread, he meets the rather indistinct narrator (a nameless hotel guest who feeds the epic tale with his own imaginings “as if it were an incurable illness”) and swiftly recounts momentous occasions in his life that occurred while living in Naples, Palermo, London, Barcelona, Brest, Rouen, and elsewhere. We learn of his “career in the service of the Special Missions,” selling information to foreign powers; his apprenticeship with a private police agency in France; his work as a Dutch sea captain searching for sites that would allow a submarine to put ashore men to pick up supplies and stockpile petrol; his experiences fighting in Sumatra with the Dutch foreign legion; as well as his collaboration with New Scotland Yard and his work as a criminal investigator in the suburbs of Düsseldorf, in search of a “fugitive monster” who “had slit the throats of young girls.”

However, the crux of his narrative has to do with the fate of the vivacious, half-Cuban, half-German beauty Signorina Bambù, with whom Hartmann falls in love in Naples when he is a young, impressionable man. Bambù, responsible for drawing him into an organization of spies, leads him across Europe, accumulating and trading information from commercial seamen and British and German officers. Hartmann lives “among the wisps of shadow cast by her secret life.”

For all Hartmann’s reminiscences about Bambù and his intoxicating romance, in reality he knows little about her other than superficial qualities. Haunted by the memory of her, he pieces together varied accounts of her adventures and her demise, never able to discern fact from fiction, and eventually concedes that the Signorina Bambù he thought he knew is merely “a literary creation.”

The other notable character in the novel is Père Barbançon, who attempts to assassinate Hartmann. In the latter section of the book, he emerges as a resident at the Boarding House of Usher, a place that, according to the unreliable and unsavory storyteller, Uhle, shelters “adventurers outside of time, men already vanished.” The inhabitants are the sort of men who have “lived the lives of small-time tradesmen, halfway between the knife and the machine gun,” and here they gather like bandits, “haunted by the silhouettes of assassins” and afraid of their own shadows.

Whereas Captain Hartmann comes across as a sermonizing, melancholic figure, it is difficult to really ascertain the true personality of Uhle, who provides much of the commentary. Orlan offers this colorful description:

Uhle was the living dead. He was, I am pretty much sure, a cross between an enumeration of juvenile experiences and a table of contents full of stillborn poems.

Measured, prudent, fiscally astute, presented as “the perfect storyteller,” he is also depicted as a crude, vile creature—a “larva crammed full of undesirable foodstuffs” with a “moth-eaten memory” and an “underdeveloped character.” Faceless, inconsistent, sometimes misleading, at times he feels like an incarnation of Barbançon, the focus of his discourse.

The pairing of Hartmann and Uhle’s narratives makes this experimental novel more disjointed and perhaps overly full of muddied memories and distorted perspectives. Regardless, Mademoiselle Bambù is an unexpected pleasure. Rich with dark humor, fertile imagination, and eloquent, intelligent reflection, it offers an admirably unique, disorienting, hallucinatory approach to storytelling.

About the Reviewer

Nicholas Litchfield is the founding editor of the literary magazine Lowestoft Chronicle, author of the suspense novel Swampjack Virus, and editor of eight literary anthologies. He has worked in various countries as a tabloid journalist, librarian, and media researcher. He writes regularly for the Colorado Review and his book reviews for the Lancashire Post are syndicated to twenty newspapers across the UK. He lives in western New York.