Book Review

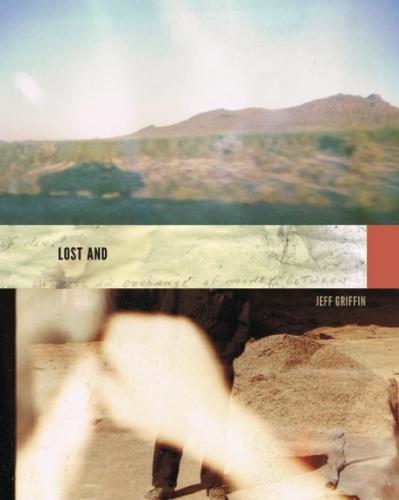

“You have just read a work of literature,” writes Mark Levine in the afterward to Jeff Griffin’s collection of artifacts (photographs, letters, journal entries, legal documents, etc.) found in abandoned dwellings like trailers and campers in the Mojave Desert. Such a reductive statement needlessly insults the reader of an otherwise rather interesting and creative contribution to the bourgeoning publication of documented poetry.

“You have just read a work of literature,” writes Mark Levine in the afterward to Jeff Griffin’s collection of artifacts (photographs, letters, journal entries, legal documents, etc.) found in abandoned dwellings like trailers and campers in the Mojave Desert. Such a reductive statement needlessly insults the reader of an otherwise rather interesting and creative contribution to the bourgeoning publication of documented poetry.

There was a time in the not-so-distant modern past when even incredibly difficult verse presented itself to the reader on its own terms. Perhaps now, in an age aptly defined by Marjorie Perloff as “unoriginal genius”—wherein instead of romantic notions of individual invention the poet acquires and manipulates citations—Levine’s summation makes sense as a kind of critical imitation of its subject matter. But does any poetry really need to be so explicitly labeled? The conventional terse blurb on the usual book jacket has here expanded to a six-page essay of justification. The critical inclusion, as opposed to the creative assemblage, ironically de-poetizes what precedes it, reverting to something akin to John Baldessari’s process of conceptual writing (“I am making art”) in the early 1970’s, though without such revolutionary implications.

The “found” that Griffin locates remains well worth discovering for oneself. Lost And’s first section, set in Brisbane Valley, offers a notebook from the 1950’s that “details a budgie’s linguistic development.” Transcribing the budgie (a small parakeet) owner’s previous transcription of the bird’s initial parroting of her English, the list of alphabetized pages presents an essential chain of signification so lyrically and linguistically playful it seems to have Stein and e.e. cummings as influences:

M

my That’s my big bird

matter What’s the matter?

Marge Sweet Marge

me Tell me a story

Even without the brief preface that refers to the scanning and transcribing of documents found by Griffin, the language reads as intriguing contemporary verse, devoid of sentimentality that cryptically leaves a page titled “F” completely blank. A brief journal entry by the owner that concludes the section foregrounds the inherently bird-human dialogic structuring of the text, placing the reader in the position of the journal writer/budgie transcriber by offering meta-commentary on the experience of the pet:

One nite he surprised me when he said, ‘Wh-e-re’s big Barbara?’ He spent

all the next day with phrases such as ‘Where’s Barbara?—Where’s the

whysky, Delbert?—and made a gramatical error, “Where’s the beer

Brarbra?’ ‘Come on, come on!’

The human’s misspellings in her critique of the bird’s grammar alone more than make this a book of poetry worthy of critical and theoretical interrogation.

Relative to many poetic traditions, America has always been invested in a kind of “first priority,”— from Emerson’s attempt to obviate the lyric self by becoming a “transparent eyeball” to Whitman’s “Adamic Will” to name things into being by crossing the relatively new landscape. Founded upon a desert sensibility, such figurative origins of American verse seem to extend to the postmodern present in the pages that follow, albeit much more locally in the West and infinitely more interiorized in photographs of people inside rooms (or with guns in the desert defensively delimiting further expansion) and writing that offers glimpses into their secret thought lives.

Summarizing the three sections that follow the budgie proves impossible, as the catalog of journal entries and photographs soon becomes too disparate to unify. In this collective sense the rhetoric proves difficult, though individually—page by page—the presentation remains as easily accessible as flipping through channels on television. Herein lies a satisfying lyric tension, as in section two where a personal sex inventory and survey (both already filled out) as well as a morality outline follow a drawing of a stick-figure mother with children and a handwritten caption that reads: “I love God! / I love the Lord. God Love me.” A few pages later, in the next section, a close up makes a cat look larger than a house. After a couple of pages of construction around Texaco and Chevron gas stations, the penultimate section features a long letter by a woman to her physically abusive boyfriend.

The inclusion of personal notes, letters, and even a handwritten William Blake poem helps keep the various photographs of low income, heavyset white Americans from seemingly excessively stereotypical. While the book itself might not seem especially classist, its marketing that promises “a portal into a world of dispossessed people and enduring desires” signals an obvious cognitive dissonance between the public it depicts in publication and the erudite readers of such verse. Though no fault of the publisher, it’s telling that these documents by the people are not really reproduced for them.

For its intended readers, the blurb on the front cover goes too far in deeming the book “more strange and disturbing than the strangest work of the surrealists” while proclaiming that “it verges on the miraculous.” Critical hyperbole, of course, is permissible, and has become so much the norm that it gets ignored anyway. This praise, however, insults Griffin’s project by misrepresenting his smart, and at times brilliant, re-presentation of a received reality by reading too much transformation into it. If the subject matter indeed looks stranger than the well-known surrealists, then the perceiver quite possibly has removed himself impossibly far from the working class reality in which so much of this country lives. Vampires interjected into the daily lives of Louisiana natives on the HBO series True Blood better matches this statement of sensational surrealism. Instead this book refreshingly offers a creative rendering of lives all too real, more like our own despite a different environment and living standard.

It’s worth stressing that the publishing framework around this collection seems at times problematic. With the new arrival of documentary poetry, more such questions about books to come will surely follow as we attempt to critically locate work in this increasingly present mode. Thankfully, inventive assemblages like this one will continue to both invite and resist definition. Like all good poetry, Lost And keeps us somewhat lost, and therefore looking.

Published: 3/24/14

About the Reviewer

Roger Sedarat is the author of two poetry collections: Dear Regime: Letters to the Islamic Republic, which won Ohio UP's 2007 Hollis Summers' Prize, and Ghazal Games (Ohio UP, 2011). He teaches poetry and literary translation the MFA Program at Queens College, City University of New York.