Book Review

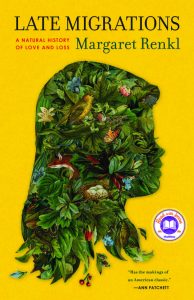

Brew a fresh cup of tea, put on your favorite sweater, and cozy up to Margaret Renkl’s debut memoir. In Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss, Renkl, a contributing writer for The New York Times and founding editor of Chapter 16, writes nature and family with keen attention to the phenomenon of life. The delicate weaving and blending of themes, feelings, and threads takes the reader through the push-and-pull of life and death as she traces her many roles: from child to writer to mother to caretaker to empty nester.

Nature and the life cycle weigh heavily on every essay in this collection.

I am a creature of piney woods and folded terrain, of birdsong and running creeks and a thousand shades of green, of forgiving soil that yields with each footfall. That hot land (Alabama) is a part of me, as fundamental to my shaping as a family member, and I would have remembered its precise features with an ache of homesickness even if I had never seen it again.

From the flora and fauna she spies from her writing desk, to the generational stories passed down alongside her Dr. W. Van Fleet roses and her caramel pound cake recipe (without “a hint of caramel in it”), to the inevitable cruelty of death that awaits us all, we are transported into a secret garden that reveals immense beauty despite, even within, the grotesque.

Striking about Late Migrations is Renkl’s ability to pull threads from nature essays directly into her familial reflections. After the telling of her father’s passing, she follows with an essay on the nesting habits of rabbits in her spring garden. In it, she relays how she and her son would clear the garden in early spring, but after disturbing a baby rabbit’s nest, she waits now until late spring when the weeds have sprung to do her weeding. The spring after her father passed, her son is away at school when she discovers another rabbit’s nest as she clears her garden. “The nest was empty but so newly vacated as to be entirely intact, an absence shaped to denote an ineffable presence.” The title of the essay, “He is Not Here,” conjures up the emptiness from her father’s death (and her son’s absence).

Renkl uses linked vignettes, ranging from several sentences to several pages to deliver her memoir. The meaning and intensity of each vignette stands alone, but together they create a complex, tightly-woven whole. Her essays on nature don’t just reveal the inevitable loss and love in the cycle of life, they provide glimpses into human nature. When talking about the squirrels infesting her attic, she says, “Sometimes I don’t even want them to move away . . . They are old friends. Their busy life above my dark room is a lullaby.” This theme is ripe throughout the memoir, revealing her desire to hold onto the past, to halt time, to invest in the microstory happening around us.

Human beings are storytelling creatures, craning to see the crumpled metal in the closed-off highway lane, working from the moment the traffic slows to construct a narrative from what’s left behind. But our tales, even the most tragic ones, hinge on specificity. The story of one drowned Syrian boy washed up in the surf keeps us awake at night with grief. The story of four million refugees streaming out of Syria seems more like a math problem.

The softness with which Renkl delivers the atrocities of life makes the joys of life shine that much brighter.

The tone and pace of each essay varies, offering relief and inspiration—even humor—between greater human observations. “The Imperfect-Family Beatitudes” shows insight into her Catholic upbringing through the eight proclamations of blessings, similar to the Beatitudes in the Gospel of Luke, though some make you laugh out loud, as in paragraphs six and seven:

Blessed is the winking father who each day delivers his children to Catholic school with a kiss and the same advice: “Give ‘em hell!” He will be summoned to few teacher conferences.

Blessed is the braless mother who arrives at the school pickup line wearing pink plastic curlers and stained house shoes, and who won’t hesitate to get out of the car if she must. She will never be kept waiting.

Blessed are the parents whose final words on leaving—the house, the car, the least consequential phone call—are always “I love you.” They will leave behind children who are lost and still found, broken and, somehow, still whole.

Like much of the book, Renkl balances moments of happiness with moments of sadness.

In “What I Saved,” she tells her mother all the possessions she saved after her death. Some are gentle confessions to her mother, and others wistful reflections:

I saved only one of your thirty-seven coffee mugs, the white one from the church in Birmingham with the massive Pieta hanging behind the altar. I keep it in the back corner of the cupboard, next to the mug emblazoned with a troubling Bible verse that gets used only when all the other mugs are dirty.

I saved three lipsticks in a shade of pink I will never wear, but I threw away two dozen more, along with bottle after bottle of expired vitamins, and don’t even get me started on the expired boxes and cans in the pantry. I wish I had known how much you loved blueberry muffins. I wish I had made you blueberry muffins every day of your life.

Like memories of lived experiences and family lore, Renkl flows through time while keeping us grounded in her own backyard. A beautiful combination of memoir and nature writing, Late Migrations feels timeless, a lifeline from our hearts to the natural world.

About the Reviewer

Aurora D. Bonner is an environmentally charged writer and artist. Her writing has appeared in Colorado Review, Brevity, Assay: Journal of Nonfiction Studies, Hippocampus Magazine, Under the Gum Tree, and elsewhere. Bonner has an MFA from Wilkes University.