Book Review

Many Romanians heralded the 1989 execution of dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu—on Christmas Day, no less—as a sign of prosperity to come. Now, more than twenty-five years later, a staggering number of citizens question whether the revolution that deposed him has made any difference. After all, despite modest improvements in living conditions over the past two decades, Romania continues to be plagued by the same corruption and crime that characterized its communist era. As New York Times columnist Patrick Basham points out, “[b]ribery is, in fact, endemic in Romanian life . . . Everyone in politics and business is presumed guilty of something.”

Many Romanians heralded the 1989 execution of dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu—on Christmas Day, no less—as a sign of prosperity to come. Now, more than twenty-five years later, a staggering number of citizens question whether the revolution that deposed him has made any difference. After all, despite modest improvements in living conditions over the past two decades, Romania continues to be plagued by the same corruption and crime that characterized its communist era. As New York Times columnist Patrick Basham points out, “[b]ribery is, in fact, endemic in Romanian life . . . Everyone in politics and business is presumed guilty of something.”

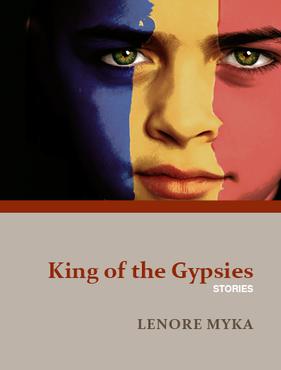

But Massachusetts-based author Lenore Myka believes there’s still hope in Romanians’ struggle. Having served there in the Peace Corps, she understands the curious combination of nobility and suffering that gives the country its distinctive character, and it is this character she aims to capture in her first story collection, King of the Gypsies. The result is a marvelous debut in which our willingness to step out of our comfort zones is tested daringly to its limits.

The title story, which opens the book, begins with a subtly powerful image that speaks to Romania’s somber history:

In the park behind the orphanage, Dragoş clambers up onto one of the few remaining stone busts of Ceauşescu, perching like an oversized pigeon on the crown of the former dictator’s head. In the hubbub following the revolution, that statue was forgotten; when it was rediscovered the locals just shrugged their shoulders. Ca să facem? they muttered to each other, but no one had a reasonable answer. They were all too exhausted by events of recent history to bother knocking it down. And so it remains, converted without needing to be redesigned into a jungle gym for Dragoş and the other children like him.

Is it incidental that Myka offers this image to us right out of the gate? Hardly. In fact, almost all of the characters in King of the Gypsies are navigating some form of post-communist wasteland, from the child thief in “Rol Doboş” who befriends a gullible American teacher, to the prostitute in “Palace Girls” tasked with disposing of best friend’s body after she has hung herself in their hotel brothel, to the Romanian transplant in “National Cherry Blossom Day” trying to appease her American husband by making friends at a grotesquely bourgeois cocktail party.

It makes sense, then, that Myka’s primary interest is the fringe members of Romanian society, the pimps and thieves and drug dealers. People with just enough left to lose to make them relatable. With simple yet elegant prose, she brings these characters to life, setting them on a perilous path between tenacity and desperation. Consider, for example, the way she characterizes fourteen-year-old sociopath Stefan in “Wood Houses”:

Stefan relies on Thomas to explain certain things because he still doesn’t understand everything the other kids in the neighborhood say. What does eat mean dope? What does eat mean pussy? In other kids these details would make them easy targets for taunting and teasing. But something about Stefan, the way his jaw sets, the way he looks at the other boys, his eyes flashing metallic, holds them back. Sometimes he pulls out a bottle he’s swiped from his adopted parents’ cabinet—vodka, vermouth, one crème de menthe—explaining that all fourteen year-olds in Romania drink alcohol. He offers some to Thomas. Always Thomas declines.

Myka’s depiction of Stefan evokes some of the same language she often uses to describe Romania itself, as in “Manna from Heaven” when the marketplace—piaţa—is depicted as “nothing but winter-hued sadness.” The country becomes a lens through which we view each of these characters, much like Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. The characters in King of the Gypsies represent specific aspects of a much larger context: the grim disparity between Romanians’ democratic aspirations prior to the revolution and their subsequent disillusionment. And while this context is universal throughout the collection, the characters’ vastly different responses make the stories that much richer.

One of the ways the author achieves this is by contrasting the austerity of Romanian ethos with Americans’ sunny naivety. In both “Lessons in Romanian” and “Manna from Heaven,” American narrators, drawn to the country to teach, find their good intentions put under scrutiny. Consider in “Manna” when Stella, our American protagonist, balks at the sight of a pig being slaughtered:

But even Magda, patient Magda, had her limits. Where do you think your precious bacon comes from, draga? she said . . . It’s a fact of life. This is how they get meat in America, too, you know. In fact, it’s probably less human there than here. At least that pig back there had a good life before it went.

Here we are shown how fragile our goodwill is when confronted with the kind of poverty that we in the West rarely experience firsthand. That’s the real story here, Romania’s ongoing struggle for identity in the wake of revolt, the realities of which are not withheld from us.

In fact, if there is any charge to level against King of the Gypsies, it might be a tendency to oversell the drama. Even Winesburg, Ohio has been accused of wistfulness and redundancy, and Gypsies has its share of similar moments. “Palace Girls,” for instance, comes dangerously close to bludgeoning us with its bleakness: “[T]he girls don’t like the English bar. The windows were shattered during the protests in ’89 and haven’t been fixed since. Rain water puddles up across the floor, mixing with grime, milky and gray, making the tiles bubble and peel, the glue from underneath catching on heels and the hems of long skirts. It reeks of mildew . . .” The writing here is wonderfully descriptive, but I still couldn’t help wondering: is there any hope left in these characters’ lives? And if not, what is our connection to them?

Fortunately, what keeps the narrative afloat in these instances is the author’s sense of control. Even when the descriptions of this depressive landscape border on repetitive, we never feel like she has lost the reins of the prose. Everything here has a purpose, including those moments of melodrama because, well, Romania is a place of melodrama. As Emma Graham-Harrison mentions in a 2014 article for the Guardian, even dissident poet Ana Blandiana, who the government put under surveillance for years, was appalled by the timing of Ceauşescu’s execution: “I thought, ‘Dear God, to kill someone on Christmas day!’ It doesn’t matter how bad they are, this should be a celebration of life.”

Even more appalling, however, is the notion that the 1989 revolution accomplished far less than most Romanians had hoped. To this day Ceauşescu is the only person to be found guilty of crimes related to the nation’s fifty-year communist regime, and the political climate has improved very little. Still, whether the revolution was indeed worth the chaos that followed is a question that Lenore Myka wants us to consider. She isn’t just telling stories here. She is sifting through a history which Western idealism tends to ignore, and by this measure King of the Gypsies isn’t just a story collection; it is a poignant reminder that complexity and virtue are only ever borne out of hardship.

About the Reviewer

Jeremy Griffin is the author of a collection of short fiction from SFASU Press titled A Last Resort for Desperate People. His work has appeared in such journals as the Indiana Review, Iowa Review, and Shenandoah. Currently, he is a lecturer in the English Department at Coastal Carolina University in Conway, South Carolina.